Bulgarian Tsar Simeon 1. Simeon (King of Bulgaria)

prince of Bulgaria from 893, from 918 - king

The Golden Age of the Bulgarian state is associated with the name of Tsar Simeon. His military campaigns against the Byzantine Empire, Hungarians and Serbs, brought the Bulgarian state to a territorial apogee, comparable only to the era of Krum. Bulgaria has become the most powerful state in the Balkans and in all of Eastern Europe.

In his time, Bulgaria stretched from Budapest, the northern slopes of the Carpathians and the Dnieper in the north to the Adriatic Sea in the west, the Aegean Sea in the south, and the Black Sea in the east.

The era of Simeon I was characterized by an unprecedented cultural upsurge, later called the golden age of Bulgarian civilization.

The state concept that Simeon approved was to build a civilized, Christian and Slavic state headed by an emperor (king), an independent (autocephalous) national church headed by a patriarch and significant book schools.

early years

Simeon was born in 864 (or 865), when Bulgaria was already Christian. He was the third son of Prince Boris and a descendant of Khan Krum. Since the throne was intended for his older brother Vladimir, Simeon was being prepared to become the head of the Bulgarian church. He received an excellent education at the most prestigious university of his time, the Magnaur School in Constantinople. Around 888 Simeon returned to Bulgaria and retired to the Preslav Monastery.

In the meantime (889), Prince Boris I also went to the monastery, and Vladimir Rasate, who reigned, tried to restore paganism.

Boris left the monastery, overthrew and blinded his eldest son (893), after which he convened a church-people's council.

The council made three important decisions: it declared Bulgarian (Church Slavonic) the official and only language of the church and state, moved the capital from Pliska to Veliki Preslav, and elevated Simeon I to the Bulgarian throne.

Trade war with Byzantium and the attack of the Hungarians (893-895)

Immediately after the coronation of Simeon, Bulgarian-Byzantine relations began to deteriorate. The Byzantine emperor Leo VI the Philosopher moved the trade of Bulgarian merchants from Constantinople to Thessaloniki and increased customs duties. Attempts by Simeon I to solve the problem peacefully were unsuccessful. The emperor relied on the inexperience of the new ruler of Bulgaria, but he was mistaken.

Simeonov Simeon

Foreword

Part one. I'm going to change

Part two. masters of the sky

Part three. Anxious nights

Part four. Higher, lower and faster

Part five. steepness

Notes

Simeonov Simeon

Tempered Wings

Publisher's note: The book by the former Deputy Minister of Defense of the People's Republic of Belarus and the Commander-in-Chief of the Air Force of the Bulgarian People's Army tells about the formation and development of military aviation in Bulgaria after the victory of the socialist revolution.

I dedicate to the revolution and its aviators, communists and Komsomol members, dead and alive, those who replace us, and those who taught us to fly, to Soviet pilots with brotherly love and the wish of bold and happy flights.

Foreword

The successes of aviation and the problems of its development have invariably attracted everyone's attention, and the heroism of pilots and the romance of their service have always owned the hearts of young men and women.

With deep knowledge of the matter, he writes about the difficult, dangerous and heroic everyday life of pilots. His book is full of sincere love for aviation.

It is well known that in order to destroy an enemy aircraft from the very first attack, a pilot must have an impeccable command of piloting technique and all means of firing, and have mature tactical thinking. In other words, in order to successfully complete the attack - the crown of the battle, the pilot must put all his strength, knowledge and experience into it. And to achieve this, it takes years of daily hard work. This is what the young cadres of the newly created military aviation in Bulgaria focused their attention on.

The book offered to the reader is a memoir written in an artistic form, it is an enthusiastic confession about the difficult deeds and heroic efforts of young guys who yesterday were partisans, and today have taken on the difficult task of creating a military aviation of a new, socialist Bulgaria. Among them you will not meet sentimental and weak people who come to despair at every aviation accident. No, in aviation, the death of a comrade is perceived as a hard, cruel lesson on a steady path forward and further, into the heavenly heights.

The author hides nothing from the reader. He honestly and frankly declares that the path to true mastery, the path to the heights of flying art for a pilot is not strewn with roses, it requires hard, often dangerous work and inhuman efforts. Sometimes along the way you lose dear comrades. And if the author remembers them, it is not only to show the difficulties, but most likely to give the dead the well-deserved honors and perpetuate the memory of them. The names of Angelov, Sodev and others are inscribed in golden letters in the history of our aviation.

I would like to warn readers against the erroneous impression that it is impossible to do without casualties in aviation. Just the opposite. These victims are rare. There are many aviation units (and among them those commanded by the author of this book), where for many years there was not a single flight accident. The author is modest and leaves the reader to guess that he himself and his life can serve as an example in this respect. After all, it was Simeon Simeonov who had the opportunity to perform the most difficult aerobatics and difficult flights in day and night conditions, moreover, on the most modern supersonic fighters. And he flew masterfully, selflessly, youthfully was in love with the sky. So it was until that tragic moment when death, caused by a serious illness, stopped his fiery heart ...

Undoubtedly, the author speaks about some events as if in passing, about others he is completely silent and focuses his attention on those episodes in which he personally plays the leading role. This manner of narration has left a certain imprint of subjectivism on the assessment of certain facts. But this does not detract from the merits of the book, because the author correctly and truthfully assesses and explains the situation. And I do not agree with those who, after reading, may admit the idea that the author exalts himself to some extent.

Simeon Simeonov does not hide his sincere feelings of respect and brotherly love for the Soviet pilot officers Yeldyshev, Drekalov, Shinkarenko and others, who gave all their strength, knowledge, experience and flying skills to help in the construction of the Bulgarian Air Force. In this regard, the book is one of the documents reflecting the truly cordial and pure friendship between Soviet and Bulgarian pilots.

The book runs as a red thread the idea that in aviation even in peaceful days the battle continues, that day and night pilots must protect the peaceful labor of workers and peasants who have taken power into their own hands. This can explain the spiritual awe that grips the reader when he reads about the dedication of his defenders, who are ready to go to any feat in order to fulfill their duty. It becomes clear to the reader how responsible the service of the pilot is, and he himself is overwhelmed by a feeling of love and pride for true patriots. Therefore, the book is read with great interest by people of all ages.

Hero of the People's Republic of Bulgaria, Hero of the Soviet Union Colonel-General of Aviation Honored Pilot Zachary Zahariev

Part one. I'm going to change

1

A clear sunny morning over the capital foreshadowed an unforgettable holiday for people. Above the earth, breathing freshness and the aroma of flowers, like a crystal dome, the azure sky sparkled, alluring and unattainable, like a dream, waiting for its conquerors. Neither music nor human hubbub could reach him - all this still belonged to the earth. Even on this solemn day, people could not tear themselves away from their earthly concerns. Some hurried to take convenient places in front of the Mausoleum, others hurried to the festive columns of demonstrators.

Cameramen and photojournalists scurried about busily, television workers prepared their cameras, filled with pride because they had to fulfill a noble mission. They were supposed to capture this day and preserve it for future generations in the same way that the Egyptian pyramids preserve to this day memories of the power of the pharaohs. On this day, it seemed, no one thought about the future, everyone sincerely rejoiced at the holiday, seized by the desire to take into memory that unusual panorama that the busy boulevard showed to the eye. Some irresistible impulse seized the people, and the rumble of their steps along the yellow cobblestones of the pavement merged with the rhythm of the music, with the festive mood of the demonstrators ...

Childishly enthusiastically succumbing to this mood, people simply forgot about the sky. And it seemed to take part in the popular rejoicing. And this time, as often happened, the sky could remind of itself with thunder and lightning, could try to force the inhabitants of the earth to honor him as a deity. The sky had the right to be angry. After all, people managed to uncover its secrets. Meteorologists have learned to predict whether there will be precipitation, whether a hurricane will blow. This time their forecasts were accurate - the day promised to be good, sunny. And so the sky decided to remind itself of itself in a different way, in order to make people talk about it and admit that only a few chosen ones, who mastered the power of thunder and lightning, were given the opportunity to rush high through its vast expanses ... The sky defended its own!

Father of Peter I. Came to power after Boris I overthrew his reigning son Vladimir Rasate, who led the pagan reaction.

The Golden Age of the Bulgarian state is associated with the name of Tsar Simeon. His military campaigns against the Byzantine Empire, Hungarians and Serbs, brought the Bulgarian state to a territorial apogee, comparable only to the era of Krum. Bulgaria has become the most powerful state in the Balkans and in all of Eastern Europe.

Simeon was born in 864 (or 865), when Bulgaria was already Christian. He was the third son of Prince Boris and a descendant of Khan Krum. Since the throne was intended for his older brother Vladimir, Simeon was being prepared to become the head of the Bulgarian church. He received an excellent education at the Magnaur school in Constantinople. Around 888 Simeon returned to Bulgaria and retired to the Preslav Monastery.

In the meantime (889), Prince Boris I also went to the monastery, and Vladimir Rasate, who reigned, tried to restore paganism.

Boris left the monastery, overthrew and blinded his eldest son (893), after which he convened a church-people's council.

The council made three important decisions: it declared Bulgarian (Church Slavonic) the official and only language of the church and state, moved the capital from Pliska to Veliki Preslav, and elevated Simeon I to the Bulgarian throne.

Immediately after the coronation of Simeon, Bulgarian-Byzantine relations began to deteriorate. The Byzantine emperor Leo VI the Philosopher moved the trade of Bulgarian merchants from Constantinople to Thessaloniki and increased customs duties. Attempts by Simeon I to solve the problem peacefully were unsuccessful. The emperor relied on the inexperience of the new ruler of Bulgaria, but he was mistaken.

In the autumn of 894, Simeon I invaded Eastern Thrace (in the Middle Ages this region was called Macedonia) and defeated the Byzantine army in a battle near Adrianople. The Roman commander Krinit was killed, and the imperial guard, which consisted of the Khazars, was captured. The Bulgarian prince ordered to cut off the noses of the guards and let them go to the emperor. These events were later called by Bulgarian historians "the first trade war in medieval Europe".

In the autumn of 894, Simeon I invaded Eastern Thrace (in the Middle Ages this region was called Macedonia) and defeated the Byzantine army in a battle near Adrianople. The Roman commander Krinit was killed, and the imperial guard, which consisted of the Khazars, was captured. The Bulgarian prince ordered to cut off the noses of the guards and let them go to the emperor. These events were later called by Bulgarian historians "the first trade war in medieval Europe".

Leo VI resorted to the traditional method of Byzantine diplomacy: to set the enemy on his enemy. With generous handouts, he persuaded the Hungarians to attack the Bulgarians. At the same time, the famous commander Nikephoros Foka the Old (840-900) was recalled from Italy and in the spring of 895 led the Byzantine army.

Simeon immediately went on a campaign against Nicephorus, but the Romans offered peace and began negotiations. Not trusting the Byzantines, Simeon I threw the imperial envoy into prison, left most of his troops in the south against Byzantium, and himself went north to fight the Hungarians. This campaign began unsuccessfully for the Bulgarians and the prince himself had to seek refuge in the fortress of Dristr. As a result, Simeon concluded a truce with Byzantium in order to focus on the war with the Hungarians.

Prince Simeon turned out to be a worthy student of Byzantine diplomacy and concluded an anti-Hungarian treaty with the Pechenegs.

In the spring of 896, Simeon moved rapidly north and met the Hungarians in a decisive battle at the Battle of the Southern Bug (modern Ukraine). In a fierce battle, the Hungarians (probably led by the legendary Arpad) suffered a heavy defeat. The Pechenegs drove the defeated Hungarians far to the west, as a result of which they settled in modern Hungary. Some historians argue that the decisive battle took place a year earlier (895) south of the Danube, and in 896 the Bulgarians carried out a punitive campaign against the Southern Bug.

Simeon "returned proud of victory and triumphant" and became "even more arrogant" (John Skylitsa and Leo Gramatik). In the summer of 896, he again moved south, completely destroyed the Roman troops at the Battle of Bulgarofigon, and laid siege to Constantinople.

Byzantium had to sign peace, cede to Bulgaria the territory between modern Strandzha and the Black Sea, and pay an annual tribute to it. The Bulgarian merchants returned to Constantinople.

Meanwhile, the Bulgarian ruler also established his control over Serbia in exchange for the recognition of Petar Gojniković as a Serbian prince.

Simeon constantly violated the peace treaty and attacked Byzantium, capturing more and more new territories.

A new peace treaty (904) established Bulgarian sovereignty over northern Greece and most of present-day Albania. The border between Bulgaria and Byzantium was 20 km north of Thessaloniki.

In May 912, Leo VI the Philosopher died and the throne was occupied by his brother Alexander as regent under the infant Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus. In the spring of 913, he refused to pay the annual tribute to Bulgaria. Simeon began military preparations, but Alexander died before the Bulgarians went on the offensive, leaving the empire in the hands of a regency council led by Patriarch Nicholas Mystik. The patriarch made great efforts to convince Simeon not to attack Byzantium, but attempts to resolve the matter amicably were unsuccessful.

In July - August 913, the Bulgarian army laid siege to Constantinople. New negotiations approved the renewal of the tribute and the marriage of Constantine VII to one of the daughters of the Bulgarian ruler, which would turn Simeon into a vasileopator (emperor's father-in-law) and give him the opportunity to rule Byzantium.

But the most significant part of the agreement is the official recognition of Simeon as the king and emperor of the Bulgarians from the Roman Patriarch Nicholas Mystic in the Blachernae Palace in Constantinople (August 913).

The act was of great importance and represented a revolution in the Byzantine ecumenical doctrine, according to which there is only one God in heaven and only one emperor on earth - the emperor of Byzantium. He is called to be the true master and father of all peoples, and other rulers are only his sons, and power can be vested exclusively by imperial permission.

In February 914, Zoya Karbonopsina, mother of Constantine VII, abolished the regency council and seized power in Byzantium. She immediately renounced the recognition of the imperial title of Simeon and refused a possible marriage between her son and Simeon's daughter.

War was the only alternative for the Bulgarian Tsar. Simeon again invaded Thrace and captured Adrianople. Byzantium began preparations for a decisive war with Bulgaria.

In the spring of 917, Byzantium's preparations for war were in full swing. The Romans were negotiating simultaneously with the Pechenegs, Hungarians and Serbs for a joint fight against Bulgaria. In June 917, peace was concluded with the Arab Caliphate, which allowed Byzantium to concentrate all its resources on the war against the Bulgarians. Elite troops and capable officers from all provinces from Armenia to Italy concentrated in Constantinople. The Bulgarians had to test the full power of the Empire.

After a solemn prayer service, a miraculous cross was brought out, before which everyone bowed and swore to win or die. In order to further raise the spirit of the soldiers, the money was paid to them in advance. The empress and the patriarch escorted the troops to the city gates. The Byzantines marched north along the coast of the Black Sea. The army was under the command of Master Leo Foki, and the fleet - the future emperor of the drungar fleet (admiral) Roman Lekapin.

On August 20, 917, north of the port of Ankhialo on the Aheloy River, the Romans and the Bulgarians met in a decisive battle. It was undoubtedly one of the greatest battles of the Middle Ages. According to the chroniclers, it can be concluded that the Bulgarians used their traditional maneuver - an offensive, a false retreat and a decisive counterattack (Markeli 792, Versiniki 813, Thessaloniki 996, Adrianople 1205). When the Byzantines were carried away by the pursuit of the retreating Bulgarians, losing strict order and opening their left flank, Simeon threw heavy cavalry from the northwest, and the entire Bulgarian army turned to a counteroffensive. The cavalry attack, led by the king himself (Simeon's horse was killed), was so swift and unexpected that it immediately swept away the left flank and went to the rear of the Byzantines. Pushed back to the sea and attacked from three sides, the Romans were completely destroyed. The commander-in-chief Leo Foka barely managed to escape, and the rest of the Byzantine generals died. The battle was, according to the chronicler Simeon Logofet, " which has not happened for a century". Leo the Deacon, who visited the battlefield 50 years later, noted: " And today you can see near Achelous heaps of bones of the then shamefully beaten, fleeing Roman army". The Bulgarian army rushed into its usual resolute strategic pursuit (after the victory at Ongle (680), the Bulgarians pursued the Byzantines for 150-200 km.).

The Pecheneg-Hungarian attack from the north failed. The Serbs also did not dare to oppose Bulgaria.

Byzantium received no help, and the Bulgarian army was already approaching its capital. In a desperate attempt to stop the Bulgarians, the Empire gathered all the troops that it still had and, having attached the remnants of the defeated Aheloy army, went out against the Bulgarian army. According to the Roman chronicler Theophan the Continuator, the Byzantine army was numerous. The commander-in-chief of the Romans was Lev Foka, eager for revenge, with his assistant Nicholas, the son of Duka.

This is how the Battle of Catasirtes, near Constantinople, took place. It was a night battle in which the Bulgarians attacked the Byzantines and defeated them again. Lev Foka fled again, and Nikolai died. The way to Constantinople was open to the army of Tsar Simeon.

However, the Bulgarian army returned back to Bulgaria. As after the battle of Cannae, when Hanibal did not continue his advance on Rome, historians cannot satisfactorily explain why Simeon did not go to Constantinople.

Immediately after the end of the campaign against Byzantium, Simeon overthrew from the Serbian throne and threw into prison Petar Gojnikovich, who tried to change him. In his place, the king put his protégé Pavel Branovic.

At the initiative of Simeon, a church council was convened (917 or 918), proclaiming the independence of the Bulgarian Church, and the newly elected patriarch consecrated Simeon's title " Simeon, by the will of Christ God, autocrat of all Bulgarians and Romans".

In 918, the Bulgarian army made a campaign in Hellas and captured Thebes.

Continuous defeats led in 919 to a coup in Byzantium. Drungarius of the fleet Roman Lecapin replaced Empress Zoya as regent, and exiled her to a monastery, after which he betrothed his daughter Elena to the infant Constantine VII and in 920 became co-emperor, having usurped real power in the empire.

This is what Simeon has been trying to do for seven years now. It became impossible to ascend the Byzantine throne by diplomatic means, and Simeon decided to start a new war.

In 920-922 the Bulgarian army launched a simultaneous attack on two fronts: in the east it overcame the Dardanelles and besieged the city of Lampsak in Asia Minor, while in the west it captured the entire territory up to the Isthmus of Corinth. In 921, the Bulgarians again captured Adrianople, which Simeon sold to Zoya in 914, and again approached Constantinople.

In the meantime (921), Roman diplomacy tried to rebel the Serbs, led by Pavel Branovic, against Simeon, but the Bulgarian autocrat replaced Paul on the Serbian throne with Zechariah and the rebellion failed.

In the east, the Bulgarian army, maneuvering near Constantinople between March 11 and 18, 922, met with the Byzantine army at Pigi. The Roman army was under the command of rector John and Pot Argyre. It also included the Imperial Guard. The flanks of the Byzantines were supported by a fleet led by the drungar of the fleet Alexei Musele.

In the battle, the Romans could not hold back the rapid advance of the Bulgarians. Some of the Byzantine soldiers were killed, the rest, including Alexei, drowned in the Golden Horn Bay.

Simeon had a powerful army, but he understood that in order to conquer Constantinople, a strong fleet was also needed in order to neutralize the Byzantine one and surround the great city from the sea. The king turned to the Arabs, who at that time had powerful naval forces. In 922 a Bulgarian embassy was sent to Caliph Ubaydallah al-Mahdi in the capital of the Fatimid Caliphate Kairouan (in present-day Tunisia). The caliph agreed to the proposal of a joint attack on Constantinople from land and sea, and sent his people to Bulgaria to clarify the details. However, on the way back they were captured by the Byzantines in Calabria (Southern Italy). Simeon made a second attempt, this time with al-Dulafi, but it also failed.

Under Byzantine influence, the Serbian Župan Zakhary rebelled against Bulgaria. In 924, Serbia was conquered and annexed to the Bulgarian kingdom, and Zacharias fled to Croatia, which was proclaimed a kingdom in 925 and a former ally of Byzantium. The Bulgarian corps led by Alogobotur invaded Croatia (926), but was ambushed in the mountains of Bosnia and defeated. Fearing a Bulgarian response, the first king of Croatia, Tomislav I, agreed to terminate the alliance with Byzantium and sign a peace on the basis of the status quo. After the conclusion of peace, Pope John X sent his legates Duke John and Bishop Madalbert to Veliki Preslav, who recognized (in the autumn of 926 the imperial title of Simeon and the patriarchate of the head of the Bulgarian church.

From the beginning of 927, despite the desperate calls for peace by Romanus Lecapenus, Simeon began large-scale preparations for the siege of Constantinople. However, this siege never took place. May 27, 927 Simeon I the Great died of heart failure in his palace in Preslav.

Simeon was brought up in Byzantium, where he stayed for 10 years, studied at the famous Magnavra school in Constantinople. Thanks to his excellent knowledge of the Greek language and culture, Simeon was called a "half-Greek." Nevertheless, the reign of Simeon was marked by continuous wars with Byzantium, which resulted in the annexation of vast territories of the Empire in the south and west to Bulgaria. The first war broke out in 894 due to a trade conflict. Byzantium managed to repel the onslaught of Simeon's troops only by entering into an alliance with the Hungarians, who entered the lower reaches of the Dniester and Danube, threatening Bulgaria. But already in 897, Simeon defeated the Byzantine army in Thrace, and in 904 he reached Thessaloniki, 20 km north of which, according to an agreement concluded in the same year, the new Byzantine-Bulgarian border passed. This 904 peace treaty established Bulgarian sovereignty over northern Greece and most of present-day Albania.

Simeon the Great

(artist D. Gyujenov)

On August 20, 917, north of the port of Ankhialo on the Aheloy River, the Romans and the Bulgarians met in a decisive battle. It was undoubtedly one of the greatest battles of the Middle Ages. According to the chroniclers, it can be concluded that the Bulgarians used their traditional maneuver - an offensive, a false retreat and a decisive counterattack (Markeli 792, Versiniki 813, Thessaloniki 996, Adrianople 1205). When the Byzantines were carried away by the pursuit of the retreating Bulgarians, losing strict order and opening their left flank, Simeon threw heavy cavalry from the northwest, and the entire Bulgarian army turned to a counteroffensive. The cavalry attack, led by the king himself (Simeon's horse was killed), was so swift and unexpected that it immediately swept away the left flank and went to the rear of the Byzantines. Pushed back to the sea and attacked from three sides, the Romans were completely destroyed. The commander-in-chief Leo Foka barely managed to escape, and the rest of the Byzantine generals died. The battle was, according to the chronicler Simeon Logofet, "which has not happened since the ages." Leo the Deacon, who visited the site of the battle 50 years later, noted: "And today, near Achelous, you can see heaps of bones of the then shamefully beaten, fleeing Roman army." The Bulgarian army rushed into its usual resolute strategic pursuit (after the victory at Ongle (680), the Bulgarians pursued the Byzantines for 150-200 km.).

The Pecheneg-Hungarian attack from the north failed. The Serbs also did not dare to oppose Bulgaria.

Byzantium received no help, and the Bulgarian army was already approaching its capital. In a desperate attempt to stop the Bulgarians, the Empire gathered all the troops that it still had and, having attached the remnants of the defeated Aheloy army, went out against the Bulgarian army. According to the Roman chronicler Theophan the Continuator, the Byzantine army was numerous. The commander-in-chief of the Romans was Lev Foka, eager for revenge, with his assistant Nicholas, the son of Duka.

This is how the Battle of Catasirtes, near Constantinople, took place. It was a night battle in which the Bulgarians attacked the Byzantines and defeated them again. Lev Foka fled again, and Nikolai died. The way to Constantinople was open to the army of Tsar Simeon.

However, the Bulgarian army returned back to Bulgaria. As after the Battle of Cannae, when Hannibal did not continue his advance on Rome, historians cannot satisfactorily explain why Simeon did not go to Constantinople.

Immediately after the end of the campaign against Byzantium, Simeon overthrew the Serbian throne and threw him into prison, who tried to change him. In his place, the king put his protege.

At the initiative of Simeon, a church council was convened (917 or 918), proclaiming the independence of the Bulgarian Church, and the newly elected patriarch consecrated Simeon's title "Simeon, by the will of Christ God, autocrat of all Bulgarians and Romans".

The consequences of the defeat were catastrophic for the Empire. Bulgarian troops entered Greece, took Thebes. The situation changed with the coming to power in Constantinople of the energetic, who managed to organize resistance to the Bulgarians. Despite the persuasion of the Patriarch of Constantinople, Nicholas the Mystic, who begged Simeon to stop the bloodshed, he believed that the moment had come for the realization of his plan to capture the Byzantine capital. The stubborn struggle continued until the death of the first Bulgarian king, the Bulgarian army appeared more than once in the vicinity of Constantinople. But in 927, Simeon's luck changed: his troops were defeated by the Croats, who had entered into an alliance with the Empire; in the same year he died. The reign of Simeon is associated with an unprecedented flowering of Bulgarian medieval culture (architectural ensembles of the new Bulgarian capital Preslav, the “golden age” of Old Bulgarian literature, the spread of Christianity and Byzantine education), prepared under his father.

For some unknown reason, Simeon deprived his eldest son Michael of the rights to the throne and sent him to a monastery. Subsequently, during the reign of the king, Michael took part in a rebellion against his brother. Another son of Simeon, Ivan, also took part in a similar rebellion.

In the meantime (921), Roman diplomacy tried to rebel the Serbs, led by Pavel Branovic, against Simeon, but the Bulgarian autocrat replaced Paul on the Serbian throne with Zechariah and the rebellion failed.

In the east, the Bulgarian army, maneuvering near Constantinople between March 11 and 18, 922, met with the Byzantine army at Pigi. The Roman army was under the command of rector John and Pot Argyre. It also included the Imperial Guard. The flanks of the Byzantines were supported by a fleet led by the drungar of the fleet Alexei Musele.

In the battle, the Romans could not hold back the rapid advance of the Bulgarians. Some of the Byzantine soldiers were killed, the rest, including Alexei, drowned in the Golden Horn Bay.

Simeon had a powerful army, but he understood that in order to conquer Constantinople, a strong fleet was also needed in order to neutralize the Byzantine one and surround the great city from the sea. The king turned to the Arabs, who at that time had powerful naval forces. In 922 a Bulgarian embassy was sent to Caliph Ubaydallah al-Mahdi in the capital of the Fatimid Caliphate Kairouan (in present-day Tunisia). The caliph agreed to the proposal of a joint attack on Constantinople from land and sea, and sent his people to Bulgaria to clarify the details. However, on the way back they were captured by the Byzantines in Calabria (Southern Italy). Simeon made a second attempt, this time with al-Dulafi, but it also failed.

Under Byzantine influence, the Serbian Župan Zakhary rebelled against Bulgaria. In 924, Serbia was conquered and annexed to the Bulgarian kingdom, and Zacharias fled to Croatia, which was proclaimed a kingdom in 925 and a former ally of Byzantium. The Bulgarian corps led by Alogobotur invaded Croatia (926), but was ambushed in the mountains of Bosnia and defeated. Fearing a Bulgarian response, the first king of Croatia, Tomislav I, agreed to terminate the alliance with Byzantium and sign a peace on the basis of the status quo. After the conclusion of peace, Pope John X sent his legates Duke John and Bishop Madalbert to Veliki Preslav, who recognized (in autumn 926) the imperial title of Simeon and the patriarchate of the head of the Bulgarian church.

From the beginning of 927, despite the desperate calls for peace by Romanus Lecapenus, Simeon began large-scale preparations for the siege of Constantinople. However, this siege never took place. May 27, 927 Simeon I the Great died of heart failure in his palace in Preslav.

Simeon's son Peter I (927-969) ascended the Bulgarian throne. In order to establish himself as a true son of a great father, he immediately invaded Eastern Thrace, capturing the fortress of Viza.

In October 927, a peace was concluded that confirmed most of Simeon's conquests. The Byzantine Empire undertook to pay an annual tribute to Bulgaria.

But the most significant thing was that from this treaty the Byzantine Empire officially recognized the imperial dignity of the Bulgarian ruler and the patriarchal status of the head of the Bulgarian church.

The marriage of Tsar Peter and the granddaughter of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Lekapin Maria was also stipulated, who was baptized under the name Irina (peace) in honor of the world.

All these results are regarded by historians as the fruits of the genius of Tsar Simeon I.

"Pax Simeonica"

Simeon intended to replace "Pax Byzantina" with "Pax Bulgarica", but he understood that this required not only human resources, but also an appropriate cultural basis.

Under his rule, the capital of Veliky Preslav flourished and turned into a prestigious religious and cultural center.

With its many churches and monasteries, the impressive royal palace and the Golden Church, Preslav was a real imperial capital. A contemporary of the construction, John Exarchus, describes the capital through the eyes of a foreigner: “When he enters the Inner City and sees the high chambers and the church, decorated on the outside with stones, wood and paints, and on the inside with marble and copper, silver and gold, he does not know what to compare them with.”

The book flourishing was especially impressive. Book schools in Ohrid, headed by St. Clement of Ohrid and in Pliska (in 893 she moved to Preslav) were founded by St. Prince Boris I, but Simeon continued the work of his father, and during his reign, Bulgarian literature reached its peak.

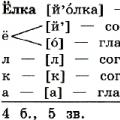

Memo "independent parts of speech"

Memo "independent parts of speech" Informative stories for children Children's popular science encyclopedia

Informative stories for children Children's popular science encyclopedia Choosing a children's encyclopedia

Choosing a children's encyclopedia