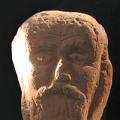

Mother of Julius Caesar. Gaius Julius Caesar - great politician and commander

One of the greatest statesmen and commanders in human history was Gaius Julius Caesar. During his reign, he included Britain, Germany and Galia, on the territory of which modern France and Belgium are located, into the Roman state. Under him, the principles of dictatorship were laid down, which served as the foundation for the Roman Empire. He also left behind a rich cultural heritage, not only as a historian and writer, but also as the author of immortal aphorisms: “I came, I saw, I conquered,” “Everyone is the smith of his own destiny,” “The die is cast,” and many others. His very name has become firmly established in the languages of many countries. From the word “Caesar” came the German “Kaiser” and the Russian “Tsar”. The month in which he was born is named in his honor - July.

Caesar's youth passed in an atmosphere of intense struggle between political groups. Having fallen out of favor with the then-ruling dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Caesar had to leave for Asia Minor and serve his military service there, while simultaneously carrying out diplomatic assignments. The death of Sulla again opened the way for Caesar to Rome. As a result of successful advancement through the political and military ladder, he became consul. And in 60 BC. formed the first triumverate - a political union between Gnaeus Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus.

Military victories

For the period from 58 to 54 BC. The troops of the Roman Republic, led by Julius Caesar, captured Galia, Germany and Britain. But the conquered territories were restless, and revolts and uprisings broke out every now and then. Therefore, from 54 to 51 BC. these lands had to be constantly recaptured. Years of wars significantly improved Caesar's financial condition. He easily spent the wealth he had, giving gifts to his friends and supporters and thereby gaining popularity. Caesar's influence on the army that fought under his command was also very great.

Civil War

During the time that Caesar fought in Europe, the first triumverate managed to disintegrate. Crassus died in 53 BC, and Pompey became close to Caesar's eternal enemy - the Senate, which on January 1, 49 BC. decided to remove Caesar's powers as consul. This day is considered the day the civil war began. Here, too, Caesar was able to show himself as a skilled commander, and after two months of civil war, his opponents capitulated. Caesar became dictator for life.

Reign and death

If this message was useful to you, I would be glad to see you in the VKontakte group. And also - thank you if you click on one of the “like” buttons: You can leave a comment on the report.

INTRODUCTION

Julius Caesar (lat. Imperator Gaius Iulius Caesar - Emperor Gaius Julius Caesar (* July 13, 100 BC - March 15, 44 BC) - ancient Roman statesman and politician, commander, writer.

Caesar's activities radically changed the cultural and political face of Western Europe and left an outstanding mark on the lives of subsequent generations of Europeans.

THE LIFE OF CAESAR AND HIS FAMILY

Gaius Julius Caesar(authentic pronunciation is close to Kaysar; lat. Gaius Iulius Caesar[ˈgaːjʊs ˈjuːliʊs ˈkae̯sar]; July 12 or 13, 100 BC. e. - March 15, 44 BC BC) - ancient Roman statesman and politician, commander, writer.

Gaius Julius Caesar was born into the ancient patrician Julian family. In the V-IV centuries BC. e. Julia played a significant role in the life of Rome. Among the representatives of the family came, in particular, one dictator, one master of cavalry (deputy dictator) and one member of the college of decemvirs, who developed the laws of the Ten Tables - the original version of the famous laws of the Twelve Tables.

Caesar was married at least three times. The status of his relationship with Cossucia, a girl from a wealthy equestrian family, is not entirely clear, which is explained by the poor preservation of sources about Caesar’s childhood and youth. It is traditionally assumed that Caesar and Cossutia were engaged, although Gaius's biographer, Plutarch, considers Cossutia to be his wife. The dissolution of relations with Cossutia apparently occurred in 84 BC. e. Very soon Caesar married Cornelia, daughter of the consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna. Caesar's second wife was Pompeia, the granddaughter of the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla (she was not a relative of Gnaeus Pompey); the marriage took place around 68 or 67 BC.

e. In December 62 BC. e. Caesar divorces her after a scandal at the festival of the Good Goddess (see section “Praetour”). For the third time, Caesar married Calpurnia from a rich and influential plebeian family. This wedding apparently took place in May 59 BC. e.

Around 78 BC e. Cornelia gave birth to Julia. Caesar arranged his daughter's engagement to Quintus Servilius Caepio, but then changed his mind and married her to Gnaeus Pompey. While in Egypt during the civil war, Caesar cohabited with Cleopatra, and presumably in the summer of 46 BC. e. she gave birth to a son known as Caesarion (Plutarch clarifies that this name was given to him by the Alexandrians, not the dictator). Despite the similarity of names and time of birth, Caesar did not officially recognize the child as his own, and contemporaries knew almost nothing about him before the assassination of the dictator. After the Ides of March, when Cleopatra's son was left out of the dictator's will, some Caesarians (in particular, Mark Antony) tried to get him recognized as heir instead of Octavian. Due to the propaganda campaign that unfolded around the issue of Caesarion's paternity, it is difficult to establish his relationship with the dictator.

A number of documents, in particular, the biography of Suetonius, and one of the epigram poems of Catullus, sometimes, as a rule, mention the story of Nicomedes. Suetonius calls this rumor " the only spot" on Guy's sexual reputation. Such hints were also made by ill-wishers. However, modern researchers draw attention to the fact that the Romans reproached Caesar not for homosexual contacts themselves, but only for his passive role in them. The fact is that in Roman opinion, any actions in a “penetrative” role were considered normal for a man, regardless of the gender of the partner.

On the contrary, the passive role of a man was considered reprehensible. According to Dio Cassius, Guy vehemently denied all hints about his connection with Nicomedes, although he usually rarely lost his temper

POLITICAL ACTIVITY OF GUY JULIUS CAESAR

Gaius Julius Caesar is the greatest commander and statesman of all times and peoples, whose name has become a household name. Caesar was born on July 12, 102 BC. As a representative of the ancient patrician Julius family, Caesar plunged into politics as a young man, becoming one of the leaders of the popular party, which, however, contradicted family tradition, since members of the family of the future emperor belonged to the optimates party, which represented the interests of the old Roman aristocracy in the Senate. In Ancient Rome, as well as in the modern world, politics was closely intertwined with family relationships: Caesar’s aunt, Julia, was the wife of Gaius Maria, who in turn was the then ruler of Rome, and Caesar’s first wife, Cornelia, was the daughter of Cinna, the successor of all that same Maria.

The development of Caesar's personality was influenced by the early death of his father, who died when the young man was only 15 years old.

Gaius Julius Caesar

Therefore, the upbringing and education of the teenager fell entirely on the shoulders of the mother. And the home tutor of the future great ruler and commander was the famous Roman teacher Mark Antony Gnifon, the author of the book “On the Latin Language”. Gniphon taught Guy to read and write, and also instilled a love of oratory, and instilled in the young man respect for his interlocutor - a quality necessary for any politician. The lessons of the teacher, a true professional of his time, gave Caesar the opportunity to truly develop his personality: read the ancient Greek epic, the works of many philosophers, get acquainted with the history of the victories of Alexander the Great, master the techniques and tricks of oratory - in a word, become an extremely developed and versatile person.

However, young Caesar showed particular interest in the art of eloquence. Before Caesar stood the example of Cicero, who made his career largely thanks to his excellent mastery of oratory - an amazing ability to convince listeners that he was right. In 87 BC, a year after his father’s death, on his sixteenth birthday, Caesar donned a one-color toga (toga virilis), which symbolized his maturity.

However, the political career of young Caesar was not destined to take off too quickly - power in Rome was seized by Sulla (82 BC). He ordered Guy to divorce his young wife, but upon hearing a categorical refusal, he deprived him of the title of priest and all his property. Only the protective position of Caesar's relatives, who were in Sulla's inner circle, saved his life.

However, this sharp turn in fate did not break Caesar, but only contributed to the development of his personality. Having lost his priestly privileges in 81 BC, Caesar began his military career, going to the East to take part in his first military campaign under the leadership of Minucius (Marcus) Thermus, the purpose of which was to suppress pockets of resistance to power in the Roman province of Asia Minor Asia, Pergamon). During the campaign, Caesar's first military glory came. In 78 BC, during the storming of the city of Mytilene (Lesbos island), he was awarded the “oak wreath” badge for saving the life of a Roman citizen.

Guy Julius Caesar is a great politician and commander. However, Caesar decided not to devote himself exclusively to military affairs. He continued his career as a politician, returning to Rome after Sulla's death. Caesar spoke at trials. The young speaker’s speech was so captivating and temperamental that crowds of people from the street gathered to listen to him. Thus Caesar multiplied his supporters. Although Caesar did not win a single judicial victory, his speech was recorded, and his phrases were divided into quotes. Caesar was truly passionate about oratory and constantly improved. To develop his oratorical talents, he went to Fr. Rhodes to learn the art of eloquence from the famous rhetorician Apollonius Molon.

In politics, Gaius Julius Caesar remained loyal to the popular party - a party whose loyalty had already brought him certain political successes. But after in 67-66. BC. The Senate and consuls Manilius and Gabinius endowed Pompey with enormous powers, Caesar began to increasingly speak out for democracy in his public speeches. In particular, Caesar proposed to revive the half-forgotten procedure of holding a trial by a popular assembly. In addition to his democratic initiatives, Caesar was a model of generosity. Having become an aedile (an official who monitored the state of the city's infrastructure), he did not skimp on decorating the city and organizing mass events - games and shows, which gained enormous popularity among the common people, for which he was also elected great pontiff. In a word, Caesar sought in every possible way to increase his popularity among citizens, playing an increasingly important role in the life of the state.

62-60 BC can be called a turning point in the biography of Caesar. During these years, he served as governor in the province of Farther Spain, where for the first time he truly revealed his extraordinary managerial and military talent. Service in Farther Spain allowed him to get rich and is paying off the debts that for a long time did not allow him to breathe deeply.

In 60 BC. Caesar returns to Rome in triumph, where a year later he is elected to the post of senior consul of the Roman Republic. In this regard, the so-called triumvirate was formed on the Roman political Olympus. Caesar's consulate suited both Caesar himself and Pompey - both claimed a leading role in the state. Pompey, who disbanded his army, which triumphantly crushed the Spanish uprising of Sertorius, did not have enough supporters; a unique combination of forces was needed. Therefore, the alliance of Pompey, Caesar and Crassus (the winner of Spartacus) was most welcome. In short, the triumvirate was a kind of union of mutually beneficial cooperation of money and political influence.

The beginning of Caesar's military leadership was his Gallic proconsulate, when large military forces came under Caesar's control, allowing him to begin his invasion of Transalpine Gaul in 58 BC. After victories over the Celts and Germans in 58-57. BC. Caesar begins to conquer the Gallic tribes. Already in 56 BC. e. the vast territory between the Alps, Pyrenees and the Rhine came under Roman rule.

Caesar rapidly developed his success: he crossed the Rhine and inflicted a number of defeats on the German tribes. Caesar's next stunning success was two campaigns in Britain and its complete subordination to Rome.

Caesar did not forget about politics. While Caesar and his political companions - Crassus and Pompey - were on the verge of a break. Their meeting took place in the city of Luca, where they reconfirmed the validity of the agreements adopted by distributing the provinces: Pompey got control of Spain and Africa, Crassus got control of Syria. Caesar's powers in Gaul were extended for the next 5 years.

However, the situation in Gaul left much to be desired. Neither thanksgiving prayers nor festivities organized in honor of Caesar's victories were able to tame the spirit of the freedom-loving Gauls, who did not give up trying to get rid of Roman rule.

In order to prevent an uprising in Gaul, Caesar decided to adhere to a policy of mercy, the basic principles of which formed the basis of all his policies in the future. Avoiding excessive bloodshed, he forgave those who repented, believing that the living Gauls who owed their lives to him were more needed than the dead.

But even this did not help prevent the impending storm, and 52 BC. e. was marked by the beginning of the Pan-Gallic uprising under the leadership of the young leader Vircingetorix. Caesar's position was very difficult. The number of his army did not exceed 60 thousand people, while the number of rebels reached 250-300 thousand people. After a series of defeats, the Gauls switched to guerrilla warfare tactics. Caesar's conquests were in jeopardy. However, in 51 BC. e. in the battle of Alesia, the Romans, although not without difficulty, defeated the rebels. Vircingetorix himself was captured and the uprising began to subside.

In 53 BC. e. A fateful event for the Roman state occurred: Crassus died in the Parthian campaign. From that moment on, the fate of the triumvirate was predetermined. Pompey did not want to comply with previous agreements with Caesar and began to pursue an independent policy. The Roman Republic was on the verge of collapse. The dispute between Caesar and Pompey for power began to take on the character of an armed confrontation.

Moreover, the law was not on Caesar’s side - he was obliged to obey the Senate and renounce his claims to power. However, Caesar decides to fight. “The die is cast,” said Caesar and invaded Italy, having only one legion at his disposal. Caesar advanced towards Rome, and the hitherto invincible Pompey the Great and the Senate surrendered city after city. Roman garrisons, initially loyal to Pompey, joined Caesar's army.

Caesar entered Rome on April 1, 49 BC. e. Caesar carries out a number of democratic reforms: a number of punitive laws of Sulla and Pompey are repealed. An important innovation of Caesar was to give the inhabitants of the provinces the rights of citizens of Rome.

The confrontation between Caesar and Pompey continued in Greece, where Pompey fled after the capture of Rome by Caesar. The first battle with Pompey's army at Dyrrhachium was unsuccessful for Caesar. His troops fled in disgrace, and Caesar himself almost died at the hands of his own standard-bearer. However, Pompey no longer posed any threat to Caesar - he was killed by the Egyptians, who sensed the direction in which the wind of political change in the world was blowing.

The Senate also felt the global changes and completely went over to Caesar’s side, proclaiming him a permanent dictator. But, instead of taking advantage of the favorable political situation in Rome, Caesar delved into solving Egyptian affairs, being carried away by the Egyptian beauty Cleopatra. Caesar's active position on domestic political issues resulted in an uprising against the Romans, one of the central episodes of which was the burning of the famous Library of Alexandria.

However, Caesar's carefree life soon ended. A new turmoil was brewing in Rome and on the outskirts of the empire. The Parthian ruler Pharnaces threatened Rome's possessions in Asia Minor. The situation in Italy also became tense - even Caesar’s previously loyal veterans began to rebel. Army of Pharnaces August 2, 47 BC. e. was defeated by Caesar’s army, who notified the Romans of such a quick victory with a short message: “He has arrived. Saw. Won."

Caesar's generosity was unprecedented: in Rome 22,000 tables were laid with refreshments for citizens, and the games, in which even war elephants participated, surpassed in entertainment all the mass events ever organized by Roman rulers. Caesar becomes dictator for life and is given the title "emperor". The month of his birth is named after him - July. Temples are built in his honor, his statues are placed among the statues of the gods. The oath form “in the name of Caesar” becomes mandatory during court hearings.

Using enormous power and authority, Caesar develops a new set of laws (“Lex Iulia de vi et de majestate”) and reforms the calendar (the Julian calendar appears). Caesar plans to build a new theater, a temple of Mars, and several libraries in Rome. In addition, preparations begin for campaigns against the Parthians and Dacians. However, these grandiose plans of Caesar were not destined to come true.

Even the policy of mercy, steadily pursued by Caesar, could not prevent the emergence of those dissatisfied with his power. So, despite the fact that Pompey's former supporters were forgiven, this act of mercy ended badly for Caesar.

On March 15, 44 BC, two days before the date of his march to the East, at a meeting of the Senate, Caesar was killed by conspirators led by former supporters of Pompey. The plans of the assassins were realized in front of numerous senators - a crowd of conspirators attacked Caesar with daggers. According to legend, having noticed his loyal supporter young Brutus among the murderers, Caesar exclaimed doomedly: “And you, my child!” (or: “And you, Brutus”) and fell at the feet of the statue of his sworn enemy Pompey.

CONCLUSION

During his reign, Caesar carried out a number of important reforms and was active in lawmaking. The Romans bowed to their ruler, but there were also dissatisfied ones. A group of senators did not like the fact that Caesar effectively became the sole ruler of Rome, and on March 15, 4 BC. the conspirators killed him right at the Senate meeting. The death of Caesar was followed by the death of the Roman Republic, on the ruins of which arose the great Roman Empire, which Julius Caesar so dreamed of.

Rome in the era of Julius Caesar was the first city whose population approached a million.

LIST OF REFERENCES USED

1. Goldsworthy A. Caesar. - M.: Eksmo

2. Grant M. Julius Caesar. Priest of Jupiter. - M.: Tsentrpoligraf

3. Durov V. S. Julius Caesar. Man and writer. - L.: Publishing House of Leningrad State University

4. Kornilova E. N. “The Myth of Julius Caesar” and the idea of dictatorship: Historiosophy and fiction of the European circle. - M.: Publishing house MGUL

5. Utchenko S. L. Julius Caesar. - M.: Thought

6. https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaius_Julius_Caesar

The nobility remained the dominant group in the state; True, there were supporters of Caesar among the Roman aristocracy. During the fight with Pompey, there were many young nobles in his camp, whose older relatives fought on Pompey’s side. Unlike Sulla Caesar dealt mercifully with his opponents. The property of only Pompey and his most consistent supporters was confiscated. Many of Caesar's former opponents received amnesty.

After defeating his enemies, Caesar definitely takes the path of reconciliation with the old aristocracy. He showers favors on prominent aristocrats, former supporters of Pompey. They are elected to the highest government positions, sent to the provinces, and given possessions as gifts. Caesar's social policy was characterized by the desire to find support from various social groups, and this is reflected in the numerous reforms he carried out.

Caesar's legislation

The last years of Caesar's activity were marked by anti-democratic reforms carried out in the spirit of the optimates and those Caesarians who shared the views of Sallust: the number of plebeians enjoying the right to receive free bread and some other products from the state was reduced from 320 to 150 thousand. A law was passed again prohibiting the colleges, which had recently been restored by Clodius. In order to reduce the number of Roman homeless and unemployed poor, 80 thousand urban proletarians were evicted by Caesar to the colonies.

Of the events carried out in the interests of the Italian inhabitants, the Julius Law on Municipalities was of particular importance, a significant part of which is known from an inscription that has survived to this day.

Reign of Julius Caesar

This law, proposed by Caesar, but apparently passed in 44 after his death, provided cities with autonomy in resolving local issues, established rules for the selection of city magistrates, gave privileges to veterans, but at the same time limited the right of association.

In the spirit of anti-plutocratic tendencies, laws were passed that protected the identity of debtors. A number of measures were supposed to help boost agriculture. The law, which limited the amounts that could be held by individuals, was intended to increase the funds invested in land holdings. Caesar was responsible for extensive projects for draining swamps, draining soil and building roads, which were only partially implemented. In the interests of the Italian rural proletariat, he established that no less than a third of the shepherds employed in the latifundia had to consist of freeborns.

Back in 59, in the year of his consulate, Caesar passed a strict law against extortion in the provinces (lex Julia de repetundis), which in its main features retained its significance throughout the existence of the Empire. Later, the tax system is streamlined: the activities of publicans are limited and brought under control; farm-outs for indirect taxes remained, while direct taxes in some provinces began to be paid to the state directly by representatives of communities.

A number of measures were supposed to promote the development of exchange. In Italy, the harbor of Rome Ostia was deepened, in Greece it was planned to dig a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth. From the time of Caesar, gold coins began to be minted regularly. The Roman denarius finally turns into a single coin for... the entire West. In the East, however, the previous diversity of monetary systems remained.

Caesar also carried out a calendar reform. With the help of the Egyptian mathematician and astronomer Sosigenes, from January 1, 45, the calculation of time was introduced, which outlived the Roman Empire by several centuries, and existed in Russia until the beginning of 1918 (the so-called Julian calendar). Caesar intended to codify Roman law, which was accomplished only in the era of the late Roman Empire.

Caesar managed to accomplish only a little of what he had planned. The entire system of his reforms was supposed to streamline various relations and prepare the merger of Rome and the provinces into a monarchy of the Hellenistic type. Rome was supposed to retain its significance only as the main city of the Roman world power, the residence of the monarch. However, they even said about Caesar that he intended to move the capital to Alexandria or Ilion.

Caesar was characterized by a combination in his reforms and projects of the traditional principles of the popular party, monarchical ideas common in the countries of the Hellenistic East, and some provisions of the Roman conservatives. In the spirit of the latter, he issued or intended to issue prohibitions against luxury and debauchery. In the interests of the most influential circles of the nobility, some senatorial families were classified as patricians (lex Cassia).

comments (0)

End of the war, Caesar's reforms.

The dictator opposed Pharnaces, the son of Mithridates, and at the Battle of Zela, Roman troops completely defeated their opponents (47 BC).

Upon his return from Rome, Caesar carried out a number of reforms.

- Arrears in rent for the past year were canceled if this payment did not exceed 2,000 sesterces.

- The law on the deduction of interest paid from the principal amount of the debt was confirmed.

- Moneylenders were prohibited, under threat of punishment, from raising interest rates above the established norm.

- Caesar took measures to demobilize and pay rewards, and settle his legionnaires in their areas. The lands of Pompey and his most prominent supporters were used for settlement. In addition to the existing remnants of the ager publicus, Caesar bought a lot of land at its normal cost, which allowed him to satisfy the land needs of his veterans. He also pioneered the distribution of land for veterans in the province.

The measures taken somewhat stabilized the situation in Italy and the eastern provinces. However, the military threat continued to exist. In Africa there was an army of Pompeys led by Pompey's father-in-law Scipio. In the spring of 46 BC. significant forces were transported to Africa, where the Pompeians were defeated near the city of Thapsus. All cities in the province capitulated to the winner.

Caesar celebrated 4 triumphs in honor of his victory in four major military campaigns. However, the war is not over yet. Pompey's sons Sextus and Gnaeus, as well as Caesar's former supporter Labienus, managed to propagate the legions in Spain in their favor and gather impressive forces. In March 45 BC. The opponents met in southern Spain near the city of Munda. In a stubborn and bloody battle, Caesar managed to snatch victory. After this victory, Caesar becomes the sole ruler of the Mediterranean power.

One of the first measures was the official consolidation of autocracy; Caesar was proclaimed by the Senate as an eternal dictator. He received the rights of a permanent proconsular empire, i.e. unlimited power over the provinces. An important prerogative of Caesar was to obtain the right to recommend candidates for master's positions.

The dictator's unlimited powers were complemented by appropriate external attributes: a purple cloak of triumph and a laurel wreath on his head, a special ivory chair with decorations. Steps were taken towards the deification of the new ruler of the state. Caesar intensively developed the idea that the goddess Venus is the ancestor of the Julian family, and he is her direct descendant.

Reforms:

- Reorganization of the Senate. Many opponents of the dictator were removed from the Senate, many were forgiven by Caesar. But a significant number of his supporters entered the Senate, and its composition expanded to 900 people.

- Caesar recommended people to the national assembly for positions. Its composition began to be dominated by veterans and urban plebs bribed with handouts.

- The number of master's programs was increased. Caesar recruited his friends and supporters to carry out government affairs and made direct appointments to positions.

- Measures were also taken to strengthen provincial local government units. Control over the activities of governors was tightened. Caesar's proxies were sent to some provinces for control. The right to collect direct taxes was transferred to local authorities. Roman tax farmers were left with the privilege of collecting only indirect taxes. Caesar's provincial policy pursued the goal of a more organic unification of the center. This was also facilitated by the policy of distributing the rights of Roman citizenship to entire settlements and cities. Provinces were included in the structure of the Roman state.

- Streamlining the system of local self-government in municipalities, colonies, cities and settlements. Activation of economic activity of the population. It was possible to return the masses of Roman legionnaires to the ground.

- Promotion of trade: in 46 BC. The previously destroyed large trade centers of the Mediterranean - Corinth and Carthage - were restored, the commercial port of Rome Ostia was reconstructed.

- Reform of the Roman calendar and transition to a new chronology system. January 1, 45 BC era, a new chronology system was introduced, called the Julian calendar.

Caesar's multifaceted reform activities were dictated by the need to solve a number of pressing social and political problems that had accumulated in society during the civil wars. As the experience of Roman history has shown, the creation of a new social and political order was possible only under the conditions of a monarchical system.

Caesar's reforms and the establishment of a monarchical system strengthened the opposition. A conspiracy was drawn up against Caesar, led by Junius Brutus, Cassius Loginus and Decimus Brutus; Cicero became the ideological inspirer of the conspiracy. The conspiracy turned out to be successful; Caesar was killed by the conspirators in the Senate.

Th triumvirate.

According to the conspirators, the murder of the dictator was supposed to lead to the abolition of the emerging monarchical structures and the automatic restoration of the republican system. However, many among the population supported the policy of centralization and a change in the political system.

After the assassination of Caesar, a sharp polarization of political forces arose. Roman society was divided into supporters of the traditional republican system and supporters of Caesar's program. The Republican party was led by Cicero, Brutus and Cassius, the Caesarian party was led by Caesar's closest associates, Mark Antony, Aemilius Lepidus, Gaius Octavius.

The Caesarians had the support of some senators. Their powerful support was also Caesar's many veterans. It was they who began to play the main role in maintaining and consolidating the regime established by Caesar. Caesarian veterans demanded decisive reprisals against the conspirators. In essence, the Caesarian army got out of the control of its leaders and did not so much carry out their political program as dictate its will to the immediate rulers, the Senate, the People's Assembly, and the provinces.

In October 43 BC. Mark Antony, Aemilius Lepidus, Gaius Octavius entered into an agreement on the establishment of the 2nd triumvirate. The Roman Senate, surrounded by Octavian's legions, could not help but approve this agreement. Under this law, the triumvirs received unlimited power for 5 years.

The triumvirs launched real terror against their opponents. Bloody proscripts were drawn up (300 senators, over 2000 horsemen and many thousands of ordinary people). They were supplemented several times based on numerous denunciations from people who were often settling personal scores. Informers appeared for the first time in Rome.

The proscriptions of the 2nd triumvirate led to the physical destruction of the Roman aristocracy, oriented towards the republican order, and to the redistribution of property.

Reign of Gaius Julius Caesar

Ordinary residents also suffered. 18 Italian cities with the most fertile soils were selected, residents were driven off their lands, and the confiscated land was distributed among veterans.

The Republican leaders Marcus Junius Brutus and Cassius Longinus managed to prepare a strong army, which was formed in Macedonia. 42 BC One of the bloodiest battles in Roman history took place near the city of Philippi. Victory was won by the triumvirs. Brutus and Cassius committed suicide.

The triumvirs failed to overcome the contradictions that arose among them. In 36 BC. Aemilius Lepidus, governor of the African provinces, tried to oppose Octavian, but was not supported by his own army. He was removed from power and exiled to one of his estates.

Power was divided between Antony, who ruled the eastern provinces, and Octavian, who ruled Italy, the western and African provinces. The decisive battle between Antony and Octavian took place in 31 BC. off Cape Aktia in western Greece. Complete victory was won by the forces of Octavian. Mark Antony fled to Alexandria with his wife Cleopatra VII. The following year, Octavian launched an attack on Egypt. Egypt was captured by Octavian, and Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide.

Occupation of Egypt in 30 BC summed up the long period of civil wars that ended with the death of the Roman Republic. The sole ruler of the Roman Mediterranean power was the official heir of Caesar, his adopted son Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian, who opened a new historical era with his reign - the era of the Roman Empire.

Caesar Gaius Julius (102-44 BC)

Great Roman commander and statesman.

Great Roman commander and statesman.

The last years of the Roman Republic are associated with the reign of Caesar, who established the regime of sole power. His name was turned into the title of the Roman emperors; From it came the Russian words “tsar”, “Caesar”, and the German “Kaiser”.

He came from a noble patrician family. Young Caesar's family connections determined his position in the political world: his father's sister, Julia, was married to Gaius Marius, the de facto sole ruler of Rome, and Caesar's first wife, Cornelia, was the daughter of Cinna, Marius's successor. In 84 BC. young Caesar was elected priest of Jupiter.

Establishment of Sulla's dictatorship in 82 BC led to Caesar's removal from his priesthood and a demand for a divorce from Cornelia. Caesar refused, which resulted in the confiscation of his wife's property and the deprivation of his father's inheritance. Sulla later pardoned the young man, although he was suspicious of him.

Having left Rome for Asia Minor, Caesar was in military service, lived in Bithynia, Cilicia, and participated in the capture of Mytilene. He returned to Rome after the death of Sulla. To improve his oratory, he went to the island of Rhodes.

Returning from Rhodes, he was captured by pirates, ransomed, but then took brutal revenge by capturing sea robbers and putting them to death. In Rome, Caesar received the positions of priest-pontiff and military tribune, and from 68 - quaestor.

Married Pompeii. Having taken the position of aedile in 66, he was engaged in the improvement of the city, organizing magnificent festivities and grain distributions; all this contributed to his popularity. Having become a senator, he participated in political intrigues in order to support Pompey, who was busy at that time with the war in the East and returned in triumph in 61.

In 60, on the eve of the consular elections, a secret political alliance was concluded - a triumvirate between Pompey, Caesar and Crassus. Caesar was elected consul for 59 together with Bibulus. Having carried out agrarian laws, Caesar acquired a large number of followers who received land. Strengthening the triumvirate, he married his daughter to Pompey.

Having become proconsul of Gaul, Caesar conquered new territories for Rome. The Gallic War demonstrated Caesar's exceptional diplomatic and strategic skill. Having defeated the Germans in a fierce battle, Caesar himself then, for the first time in Roman history, undertook a campaign across the Rhine, crossing his troops across a specially built bridge.

He also made a campaign to Britain, where he won several victories and crossed the Thames; however, realizing the fragility of his position, he soon left the island.

In 54 BC. Caesar urgently returned to Gaul in connection with the uprising that had begun there. Despite desperate resistance and superior numbers, the Gauls were again conquered.

As a commander, Caesar was distinguished by decisiveness and at the same time caution, he was hardy, and on a campaign he always walked ahead of the army with his head uncovered, both in the heat and in the cold. He knew how to set up soldiers with a short speech, personally knew his centurions and the best soldiers and enjoyed extraordinary popularity and authority among them

After the death of Crassus in 53 BC. the triumvirate fell apart. Pompey, in his rivalry with Caesar, led the supporters of Senate republican rule. The Senate, fearing Caesar, refused to extend his powers in Gaul. Realizing his popularity among the troops and in Rome, Caesar decides to seize power by force. In 49, he gathered the soldiers of the 13th Legion, gave them a speech and made the famous crossing of the Rubicon River, thus crossing the border of Italy.

In the very first days, Caesar occupied several cities without encountering resistance. Panic began in Rome. Confused Pompey, the consuls and the Senate left the capital. Having entered Rome, Caesar convened the rest of the Senate and offered cooperation.

Caesar quickly and successfully campaigned against Pompey in his province of Spain. Returning to Rome, Caesar was proclaimed dictator. Pompey hastily gathered a huge army, but Caesar inflicted a crushing defeat on him in the famous battle of Pharsalus. Pompey fled to the Asian provinces and was killed in Egypt. Pursuing him, Caesar went to Egypt, to Alexandria, where he was presented with the head of his murdered rival. Caesar refused the terrible gift and, according to biographers, mourned his death.

While in Egypt, Caesar became immersed in the political intrigues of Queen Cleopatra; Alexandria was subdued. Meanwhile, the Pompeians were gathering new forces based in North Africa. After a campaign in Syria and Cilicia, Caesar returned to Rome and then defeated the supporters of Pompey at the Battle of Thapsus (46 BC) in North Africa. The cities of North Africa expressed their submission.

Upon returning to Rome, Caesar celebrates a magnificent triumph, arranges grandiose shows, games and treats for the people, and rewards the soldiers. He is proclaimed dictator for 10 years and receives the titles of “emperor” and “father of the fatherland.” Conducts numerous laws on Roman citizenship, reform of the calendar, which receives his name.

Statues of Caesar are erected in temples. The month of July is named after him, the list of Caesar's honors is written in gold letters on silver columns. He autocratically appoints and removes officials from power.

Discontent was brewing in society, especially in republican circles, and there were rumors about Caesar's desire for royal power. His relationship with Cleopatra also made an unfavorable impression. A plot arose to assassinate the dictator. Among the conspirators were his closest associates Cassius and the young Marcus Junius Brutus, who, it was claimed, was even the illegitimate son of Caesar. On the Ides of March, at a meeting of the Senate, the conspirators attacked Caesar with daggers. According to legend, seeing young Brutus among the murderers, Caesar exclaimed: “And you, my child” (or: “And you, Brutus”), stopped resisting and fell at the foot of the statue of his enemy Pompey.

Caesar went down in history as the largest Roman writer; his “Notes on the Gallic War” and “Notes on the Civil War” are rightfully considered an example of Latin prose.

the site decided to talk about the women of one of the greatest rulers of the Roman Empire - Gaius Julius Caesar.

Cornelia Zinilla

Cornelia was the daughter of the patrician Lucius Cornelius Cinna, who served as consul subsequently from 87 to 84 BC. e. including a Roman woman named Annia. Her dad was a supporter of Marius, in 84 BC. e. marched with troops against Sulla, who was returning from the war with Mithridates, and was nevertheless killed by his soldiers in Liburnia (modern Croatia). In 85 BC e. year Caesar becomes the flamen of Jupiter. Since this place could only be occupied by patricians who were not related to other classes, he broke off his engagement with Cossutia, the daughter of a rich horseman, to whom he had been engaged since childhood. In 83 BC. e. He, it seems out of love, takes Cornelia Cinna as his wife.

Immediately after the wedding, Sulla orders Caesar to divorce Cornelia

Almost immediately after this wedding, Sulla orders Caesar to divorce his wife. The same order was received by Marcus Piso, who married the widow of Lucius Cornelius Annia. Unlike Piso, Caesar refuses. Perhaps Sulla saw in this proud seventeen-year-old youth a strong political opponent; rather, it was revenge on the descendants and relatives of Lucius Cornelius, despite all this, Caesar was deprived of his entire fortune, the post of flamen, and his mistress - her dowry. The couple had to take cover for some time, the danger of death was so great. Caesar's mother, Aurelia Cotte, had to use all the influence of her relatives so that Caesar would not be included in the proscription lists. In 82 BC e. Cornelia gives birth to a daughter. The family has to move to Asia Minor, where Caesar serves under the command of the propraetor Marcus Minucius Termus. The storm passed in 78 BC. e., when Sulla died. The couple returns to Rome, where Cornelia lives continuously from that time on. In 68, Cornelia dies giving birth to her second child.

Pompey Sulla

Pompeia came from the plebeian family of Pompeii. Her father wasQuintus Pompey Rufus, consul of 88 BC. e. , together with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Her mother, Cornelia Sulla, was Sulla's eldest daughter, whom he married to Quintus Pompey in order to strengthen his affection for him.

Caesar married Pompey in 68 BC e. , after his first wife died in childbirth a year earlier Cornelia Cinna . This was also Pompeii's second marriage. Before that, she was married for three years toGaius Servilius Vatia, nephew of Publius Servilius Vatius of Isauria, consul 78 BC e. . Gaius Servilius was appointedconsul-suffect, however, he died before he could take office and left Pompey a widow.

The marriage to Sulla's granddaughter may seem strange, especially considering the persecution that Caesar suffered from him, but it was necessary for Caesar, since on her paternal side Pompey was a relative of Pompey the Great. This marriage sealed the rapprochement between Caesar and Pompey. The organizer of the marriage was Caesar's mother, Aurelia Cotta.

They married when Pompey was about 22 years old. According to indirect sources, Pompeii was a beauty. According to descriptions, she was of average height, had a good figure, thin bones; the face is a regular oval, dark red hair, bright green eyes.

Caesar married Pompey when she was about 22 years old

However, the couple did not seem to have any feelings for each other, especially Caesar. He believed that she "likes to spend money, is lazy and is monumentally stupid." The relationship between the spouses can be indirectly confirmed by the absence of children from the couple during 6 years of marriage.

In 62 BC e. Aurelius Cotta exposed Publius Clodius Pulchra, who, disguised as a woman, was escorted by his sister,Claudia Pulhra Tertia on Mysteries of the Good Goddesswhich took place in Caesar's house. A documentary record of this can be read in the “Biography of Cicero”Leonardo Bruni Aretino. This episode is also described in The Ides of MarchThornton Wilder.

The real reason for this behavior of Publius Clodius was his interest in Pompey Sulla. Caesar, then in officePontifex Maximus, after this incident, immediately divorces his wife, although he suggests that she may be innocent. "Caesar's wife must be above suspicion."

After the divorce, she most likely married Caesar's client and associate Publius Vatinius , consul 47 BC e., who had recently lost his first wife.

Calpurnia Pizonis

Calpurnia came from the ancient plebeian family of the Calpurnias. Her father was Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesonnius, consul of 58 BC. e. On her mother's side, Calpurnia was a distant relative of Aurelia Cotta, the mother of Caesar, as well as of Pompey the Great. The name of Calpurnia's mother is not known for sure.

Her date of birth is also unknown. She married Caesar in 59 BC. e. Since this was her first marriage, and girls in Rome were usually married at the age of 15-16, we can assume that she was born around 76 BC. e.

There are no clearly established images of Calpurnia, but a bust is attributed to her, which can be seen at this link: Bust of Calpurnia.

Calpurnia was married to Caesar in 59 BC. e. Immediately after her marriage, her father becomes, under the patronage of Caesar, consul, along with his comrade-in-arms, Aulus Gabinius.

There is very little information about Calpurnia. It is known that Caesar was not permanent in his marriage and had a large number of side relationships. However, a good relationship between the spouses is suggested by the fact that on the eve of his death (after 15 years of marriage), Caesar still spends the night on the female side of his house.

Caesar had a large number of side relationships in his marriage to Calpurnia

According to numerous testimonies, on the night before Caesar's death, Calpurnia had a terrible dream.

Waking up, Calpurnia dissuades Caesar from going to the Senate, but he ignores her requests. A few hours later, Caesar was assassinated in the Senate.

After the death of Caesar, the fate of Calpurnia is unknown, and she is not mentioned in the works of ancient historians. It is known from indirect sources that, most likely, she did not remarry and did not have children. She lived in Herculaneum in prosperity and honor, since the Calpurnius family was rich. The only written mention of her after Caesar's death is in the tombstone inscription on the grave of her freedman Icadion, found in Herculaneum.

Servilia

Servilia came from an ancient famous patrician family; her brother was Marcus Porcius Cato, the most consistent defender of the republic and the implacable enemy of Gaius Julius Caesar.

Servilia's first husband, Marcus Junius Brutus, came from an old family, very famous for its republican traditions. He gave her a son (also Mark) and died in an internecine war in 77 BC. e.

The second husband, Decimus Junius Silanus, was also not the last man in Rome; in 70 BC e. he was elected aedile, and in 62 BC. e. occupies the highest position in the state - becomes consul. Servilia bore him three daughters, who received the name Junia (the Romans added the numeral to the same names of daughters - First, Second, Third).

Servilia cheated on her husbands with the one whom she considered the greatest love of her life - with Gaius Julius Caesar. Plutarch tells an incident that occurred during a meeting of the Senate: “When there was an intense struggle and a heated argument between Caesar and Cato, and the attention of the entire Senate was focused on the two of them, Caesar was given a small tablet from somewhere. Cato suspected something was wrong and, wanting to cast a shadow on Caesar, began to accuse him of secret connections with the conspirators and demanded to read the note out loud. Then Caesar handed the tablet directly into the hands of Cato, and he read the shameless letter of his sister Servilia to Caesar, who seduced her and whom she dearly loved.

Servilia considered Caesar the greatest love of her life

After the death of her second husband, Decimus Silanus, in 61 BC. e. Servilia never married again and devoted herself entirely to her beloved Caesar. It seems that even time had no power over this great love: when Silanus died, Servilia was about 40 years old, and during the civil war she was already over 50. True, the insidious sister of Cato used a good bait to keep Caesar near her and take advantage of not only him love.

Naturally, Marcus Brutus fought against Caesar, but he was luckier than Cato.

The most interesting thing is that Julius Caesar took care of his enemy as if he were his closest person. On the eve of the Battle of Pharsalus, Caesar “ordered the commanders of his legions not to kill Brutus in battle, but to deliver him alive if he surrendered voluntarily, and if he offered resistance, to release him without using violence.”

Plutarch explains the reason for Caesar’s mercy: “He gave such an order to please Servilia, the mother of Brutus. It is known that in his youth he was in a relationship with Servilia, who was madly in love with him, and Brutus was born in the midst of this love, and therefore Caesar could consider him his son.”

Brutus managed to survive the Battle of Pharsalus; he reached Larissa safely and from there he wrote to Julius Caesar. “Caesar was glad to see him saved, called Brutus to him and not only freed him from all guilt, but also accepted him as one of his closest friends” (Plutarch). Brutus even convinced his patron to forgive Cassius as well.

Caesar hoped to win over Servilia's son with his mercy. He received the highest of praetorships, and three years later was to become consul. Preparing to cross to Africa to fight Cato and Scipio, Caesar appointed Brutus ruler of Pre-Alpine Gaul. According to Plutarch, “Brutus generally enjoyed the power of Caesar to the extent that he himself desired it. If he had his way, he could have become the first among the dictator’s associates and the most influential person in Rome. But respect for Cassius tore him away from Caesar..."

Cleopatra

Queen Cleopatra of Egypt was born in 69 BC. e, and died in 30 BC. e. She lived a relatively short but bright life, leaving behind many secrets and mysteries. 2 thousand years have already passed since the death of this amazing woman, and humanity cannot forget her name.

Cleopatra's origins were the most noble. She belonged to the Ptolemaic dynasty, who ruled Egypt for 300 years. The founder of the dynasty was Ptolemy Lagus or Ptolemy I, son of Lagus. He was a military commanderAlexander the Great, and after his death founded a separate state in Egypt - the so-called Hellenistic Egypt with its capital in the city of Alexandria.

The future queen's relationship with her father was very good. In 51 BC. e. the king fell seriously ill. Sensing the end was near, he appointed Cleopatra as co-ruler. At this time she turned 18 years old. Having received the title of queen, the girl began to be called Cleopatra VII.

Queen Cleopatra of Egypt was distinguished by her extraordinary intelligence and strong character. There was no way for her to push around. The girl strove for absolute power. She also wanted to rid the country of Roman dependence and turn Egypt into a strong power, which it was under the first Ptolemies.

Surrounded by the young king, the tone was set by the eunuch Pothinus and the boy’s teacher Theodat. They had enormous influence on Ptolemy XIII and dreamed of uncontrolled and absolute power. Skillfully playing on the ambition of other subjects, these people organized a conspiracy. His goal was to kill Cleopatra. But the young queen learned about the impending crime in time. In 48 BC. e. She, along with her younger sister Arsinoe, fled by ship to the lands of Syria.

Here the queen managed to gather a mercenary army, borrowing money from local rulers and merchants. The girl had amazing charm and eloquence. The men were in awe of her and could not refuse money. As a result, Cleopatra VII stood at the head of a fairly strong military unit.

Caesar understands the existing opposition in the country. He declares that he will take on the role of arbiter and will try to sort out the quarrel between the king and queen. A messenger is sent to Cleopatra with an offer to come to Alexandria and meet with the Roman dictator. The girl has no choice but to give consent. But she cannot appear openly in the city, because she is afraid of being killed by her brother’s henchmen.

The way out, however, is found quickly. The queen boards a boat with her devoted admirer Apollodorus and thus ends up in Alexandria. But you still need to get into the palace and see the formidable Roman commander. This task is quite difficult, since there are a lot of Ptolemy XIII’s people in the palace chambers, and they all know the girl by sight.

Cleopatra climbs into a large bag intended for bedding, Apollodorus puts it on his shoulder and freely passes into the premises where Gaius Julius Caesar is located.

Cleopatra is delivered to Caesar in a bedding bag

The young queen appears before the formidable dictator and makes an indelible impression on a mature man who has already exchanged fifty dollars. The Roman is fascinated, but political interests come first. However, he had long ago decided to bet on the queen, moreover, this is fully consistent with the royal will of the late Ptolemy XII.

The next morning, the dictator tells the young king that he considers Cleopatra the rightful heir to the throne and sees no point in depriving her of her royal rank.

Power over Egypt is concentrated in the hands of the young queen. She appoints her youngest brother, Ptolemy XIV, as her co-ruler. In 47 BC. e. he has just turned 13 years old.

The new rulers organize lavish celebrations. A huge fleet of 400 festively decorated ships sails along the Nile. Crowned brother and sister and Julius Caesar stand on the deck of one of them. The people rejoice and rejoice. Finally, Queen Cleopatra of Egypt gains full power. True, she is limited by the Roman protectorate, but this only plays into the hands of the young woman.

At the beginning of June, the dictator leaves for Rome, and literally 3 weeks later the young queen begins to go into labor. She gives birth to a boy and names him Ptolemy Caesar. The entire royal entourage understands whose child this is. He is given the nickname Caesarion. It is with him that the boy goes down in history.

A year passes, and Julius Caesar summons his crowned brothers and sister to Rome. There is a formal reason for this. The conclusion of an alliance between the Roman Republic and Egypt. But the real reason is that the dictator missed his beloved.

In the capital, visitors have full disposal of a luxurious villa surrounded by gardens on the banks of the Tiber River. Here the dictator's beloved receives the Roman nobility. Everyone is in a hurry to pay their respects to the queen, because this also means respect to Caesar.

But there are many people in Rome who are very irritated by this. The situation is aggravated by the fact that the elderly lover ordered a statue of his favorite to be made. He ordered to place it next to the altar of the goddess Venus.

The happy existence lasts just over two and a half years. In mid-March 44 BC. e. The Roman dictator is assassinated by conspirators.

In Rome, thereby hinting at his relationship with the goddess. Cognomen Caesar made no sense in Latin; Soviet historian of Rome A.I. Nemirovsky suggested that it comes from Cisre- the Etruscan name of the city of Cere. The antiquity of the Caesar family itself is difficult to establish (the first known one dates back to the end of the 5th century BC). The father of the future dictator, also Gaius Julius Caesar the Elder (proconsul of Asia), stopped in his career as a praetor. On his mother's side, Caesar came from the Cotta family of the Aurelian family with an admixture of plebeian blood. Caesar's uncles were consuls: Sextus Julius Caesar (91 BC), Lucius Julius Caesar (90 BC)

Gaius Julius Caesar lost his father at the age of sixteen; He maintained close friendly relations with his mother until her death in 54 BC. e.

A noble and cultured family created favorable conditions for his development; careful physical education later served him considerable service; a thorough education - scientific, literary, grammatical, on Greco-Roman foundations - formed logical thinking, prepared him for practical activity, for literary work.

Marriage and service in Asia

Before Caesar, the Julian family, despite their aristocratic origins, was not rich by the standards of the Roman nobility of that time. That is why, until Caesar himself, almost none of his relatives achieved much influence. Only his paternal aunt, Julia, married Gaius Marius, a talented commander and reformer of the Roman army. Marius was the leader of the democratic faction of the populares in the Roman Senate and sharply opposed the conservatives from the optimates faction.

Internal political conflicts in Rome at that time reached such severity that they led to civil war. After the capture of Rome by Marius in 87 BC. e. For a time, the power of the popular was established. The young Caesar was awarded the title of Flaminus Jupiter. But, in 86 BC. e. Mari died, and in 84 BC. e. During a riot among the troops, the consul Cinna, who usurped power, was killed. In 82 BC e. Rome was taken by the troops of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, and Sulla himself became dictator. Caesar was connected by double family ties with the party of his opponent - Maria: at the age of seventeen he married Cornelia, the youngest daughter of Lucius Cornelius Cinna, an associate of Marius and the worst enemy of Sulla. This was a kind of demonstration of his commitment to the popular party, which by that time had been humiliated and defeated by the all-powerful Sulla.

In order to perfectly master the art of oratory, Caesar specifically in 75 BC. e. went to Rhodes to the famous teacher Apollonius Molon. Along the way, he was captured by Cilician pirates, for his release he had to pay a significant ransom of twenty talents, and while his friends collected money, he spent more than a month in captivity, practicing eloquence in front of his captors. After his release, he immediately assembled a fleet in Miletus, captured the pirate fortress and ordered the captured pirates to be crucified on the cross as a warning to others. But, since they treated him well at one time, Caesar ordered their legs to be broken before the crucifixion in order to alleviate their suffering (if you break the legs of a crucified person, he will die quite quickly from asphyxia). Then he often showed condescension towards defeated opponents. This is where the “mercy of Caesar”, so praised by ancient authors, was manifested.

Caesar takes part in the war with King Mithridates at the head of an independent detachment, but does not remain there for long. In 74 BC e. he returns to Rome. In 73 BC e. he was co-opted to the priestly college of pontiffs in place of the deceased Lucius Aurelius Cotta, his uncle.

Subsequently, he wins the election to the military tribunes. Always and everywhere, Caesar never tires of reminding of his democratic beliefs, connections with Gaius Marius and dislike for aristocrats. Actively participates in the struggle for the restoration of the rights of the people's tribunes, curtailed by Sulla, for the rehabilitation of the associates of Gaius Marius, who were persecuted during the dictatorship of Sulla, and seeks the return of Lucius Cornelius Cinna - the son of the consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna and the brother of Caesar's wife. By this time, the beginning of his rapprochement with Gnaeus Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus began, on a close connection with whom he built his future career.

Caesar, being in a difficult position, does not say a word to justify the conspirators, but insists on not subjecting them to the death penalty. His proposal does not pass, and Caesar himself almost dies at the hands of an angry crowd.

Spain Far (Hispania Ulterior)

(Bibulus was consul only formally; the triumvirs actually removed him from power).

Caesar's consulate is necessary for both him and Pompey. Having disbanded the army, Pompey, for all his greatness, turns out to be powerless; None of his proposals pass due to the stubborn resistance of the Senate, and yet he promised his veteran soldiers land, and this issue could not tolerate delay. Supporters of Pompey alone were not enough; a more powerful influence was needed - this was the basis of Pompey’s alliance with Caesar and Crassus. The consul Caesar himself was in dire need of the influence of Pompey and the money of Crassus. It was not easy to convince the former consul Marcus Licinius Crassus, an old enemy of Pompey, to agree to an alliance, but in the end it was possible - this richest man in Rome could not get troops under his command for the war with Parthia.

This is how what historians would later call the first triumvirate arose - a private agreement of three persons, not sanctioned by anyone or anything other than their mutual consent. The private nature of the triumvirate was also emphasized by the consolidation of its marriages: Pompey to Caesar’s only daughter, Julia Caesaris (despite the difference in age and upbringing, this political marriage turned out to be sealed by love), and Caesar to the daughter of Calpurnius Piso.

At first, Caesar believed that this could be done in Spain, but a closer acquaintance with this country and its insufficiently convenient geographical position in relation to Italy forced Caesar to abandon this idea, especially since the traditions of Pompey were strong in Spain and in the Spanish army.

The reason for the outbreak of hostilities in 58 BC. e. in Transalpine Gaul there was a mass migration to these lands of the Celtic tribe of the Helvetii. After the victory over the Helvetii in the same year, a war followed against the Germanic tribes invading Gaul, led by Ariovistus, ending in the complete victory of Caesar. Increased Roman influence in Gaul caused unrest among the Belgae. Campaign 57 BC e. begins with the pacification of the Belgae and continues with the conquest of the northwestern lands, where the tribes of the Nervii and Aduatuci lived. In the summer of 57 BC e. on the bank of the river Sabris took place a grandiose battle of the Roman legions with the army of the Nervii, when only luck and the best training of the legionnaires allowed the Romans to win. At the same time, a legion under the command of legate Publius Crassus conquered the tribes of northwestern Gaul.

Based on Caesar's report, the Senate was forced to decide on a celebration and a 15-day thanksgiving service.

As a result of three years of successful war, Caesar increased his fortune many times over. He generously gave money to his supporters, attracting new people to himself, and increased his influence.

That same summer, Caesar organized his first, and the next, 54 BC. e. - second expedition to Britain. The legions met such fierce resistance from the natives here that Caesar had to return to Gaul with nothing. In 53 BC e. Unrest continued among the Gallic tribes, who could not come to terms with oppression by the Romans. All of them were pacified in a short time.

By agreement between Caesar and Pompey in Lucca in 56 BC. e. and the subsequent law of Pompey and Crassus in 55 BC. e. , Caesar's powers in Gaul and Illyricum were to end on the last day of February 49 BC. e. ; Moreover, it was definitely indicated that until March 1, 50 BC. e. there will be no talk in the Senate about a successor to Caesar. In 52 BC e. Only the Gallic unrest prevented a break between Caesar and Pompey, caused by the transfer of all power into the hands of Pompey, as a single consul and at the same time proconsul, which upset the balance of the duumvirate. As compensation, Caesar demanded for himself the possibility of the same position in the future, that is, the union of the consulate and the proconsulate, or, rather, the immediate replacement of the proconsulate by the consulate. To do this, it was necessary to obtain permission to be chosen as consul in 48 BC. e. , not entering during 49 BC. e. to the city, which would be tantamount to a renunciation of military authority.

Late in the spring, Caesar left Egypt, leaving Cleopatra and her husband, Ptolemy Jr. as queen (the elder was killed at the Battle of the Nile). Caesar spent 9 months in Egypt; Alexandria - the last Hellenistic capital - and the court of Cleopatra gave him many impressions and a lot of experience. Despite urgent matters in Asia Minor and the West, Caesar went from Egypt to Syria, where, as the successor of the Seleucids, he restored their palace in Daphne and generally behaved like a master and monarch.

In July, he left Syria, quickly dealt with the rebel Pontic king Pharnaces and hurried to Rome, where his presence was urgently needed. After the death of Pompey, his party and the party of the Senate were far from broken. There were quite a few Pompeians, as they were called, in Italy; They were more dangerous in the provinces, especially in Illyricum, Spain and Africa. Caesar's legates barely managed to subjugate Illyricum, where Marcus Octavius had been resisting for a long time, not without success. In Spain, the mood of the army was clearly Pompeian; All the prominent members of the Senate party gathered in Africa, with a strong army. There were Metellus Scipio, the commander-in-chief, and the sons of Pompey, Gnaeus and Sextus, and Cato, and Titus Labienus, and others. They were supported by the Moorish king Juba. In Italy, the former supporter and agent of Julius Caesar, Caelius Rufus, became the head of the Pompeians. In alliance with Milo, he started a revolution on economic grounds; using his magistracy (praetour), he announced a deferment of all debts for 6 years; when the consul removed him from the magistracy, he raised the banner of rebellion in the south and died in the fight against government troops.

In 47 Rome was without magistrates; M. Antony ruled it as magister equitum of the dictator Julius Caesar; the troubles arose thanks to the tribunes Lucius Trebellius and Cornelius Dolabella on the same economic basis, but without the Pompeian lining. It was not the tribunes that were dangerous, however, but Caesar’s army, which was to be sent to Africa to fight the Pompeians. The long absence of Julius Caesar weakened discipline; the army refused to obey. In September 47, Caesar reappeared in Rome. With difficulty he managed to calm the soldiers who were already moving towards Rome. Having quickly completed the most necessary matters, in the winter of the same year Caesar crossed over to Africa. The details of this expedition of his are poorly known; a special monograph on this war by one of his officers suffers from ambiguities and bias. And here, as in Greece, the advantage was initially not on his side. After a long sitting on the seashore awaiting reinforcements and a tedious march inland, Caesar finally succeeds in forcing the battle of Thapsus, in which the Pompeians were completely defeated (April 6, 46). Most of the prominent Pompeians died in Africa; the rest escaped to Spain, where the army took their side. At the same time, fermentation began in Syria, where Caecilius Bassus had significant success, seizing almost the entire province into his own hands.

On July 28, 46, Caesar returned from Africa to Rome, but stayed there only for a few months. Already in December he was in Spain, where he was met by a large enemy force led by Pompey, Labienus, Atius Varus and others. The decisive battle, after a tiring campaign, was fought near Munda (March 17, 45). The battle almost ended in Caesar's defeat; his life, as recently in Alexandria, was in danger. With terrible efforts, victory was snatched from the enemies, and the Pompeian army was largely cut off. Of the party leaders, only Sextus Pompey remained alive. Upon returning to Rome, Caesar, along with the reorganization of the state, prepared for a campaign in the East, but on March 15, 44 he died at the hands of the conspirators. The reasons for this can only be clarified after analyzing the reform of the political system that was started and carried out by Caesar in the short periods of his peaceful activity.

The power of Julius Caesar

Statue of Caesar in the garden of the Palace of Versailles (1696, sculptor Coustou)

Over the long period of his political activity, Julius Caesar clearly understood that one of the main evils causing a serious illness of the Roman political system is the instability, impotence and purely urban nature of the executive power, the selfish, narrow party and class nature of the power of the Senate. From the early moments of his career, he openly and definitely struggled with both. And in the era of the conspiracy of Catiline, and in the era of extraordinary powers of Pompey, and in the era of the triumvirate, Caesar consciously pursued the idea of centralization of power and the need to destroy the prestige and importance of the Senate.

Monument to Julius Caesar in Rome

Individuality, as far as one can judge, did not seem necessary to him. The agrarian commission, the triumvirate, then the duumvirate with Pompey, to which Yu. Caesar clung so tenaciously, show that he was not against collegiality or the division of power. It is impossible to think that all these forms were for him only a political necessity. With the death of Pompey, Caesar effectively remained the sole leader of the state; the power of the Senate was broken and power was concentrated in one hand, as it once was in the hands of Sulla. In order to carry out all the plans that Caesar had in mind, his power had to be as strong as possible, as unconstrained as possible, as complete as possible, but at the same time, at least at first, it should not formally go beyond the framework of the constitution. The most natural thing - since the constitution did not know a ready-made form of monarchical power and treated royal power with horror and disgust - was to combine in one person powers of an ordinary and extraordinary nature around one center. The consulate, weakened by the entire evolution of Rome, could not be such a center: a magistracy was needed, not subject to intercession and veto of the tribunes, combining military and civil functions, not limited by collegiality. The only magistracy of this kind was the dictatorship. Its inconvenience compared to the form invented by Pompey - the combination of a sole consulate with a proconsulate - was that it was too vague and, while giving everything in general, did not give anything in particular. Its extraordinaryness and urgency could be eliminated, as Sulla did, by pointing to its permanence (dictator perpetuus), while the uncertainty of powers - which Sulla did not take into account, since he saw in the dictatorship only a temporary means for carrying out his reforms - was eliminated only through the above connection . Dictatorship, as a basis, and next to this a series of special powers - this, therefore, is the framework within which Yu. Caesar wanted to place and placed his power. Within these limits, his power developed as follows.

In 49 - the year of the beginning of the civil war - during his stay in Spain, the people, at the suggestion of the praetor Lepidus, elected him dictator. Returning to Rome, Yu. Caesar passed several laws, assembled a comitia, at which he was elected consul for the second time (for the year 48), and abandoned dictatorship. The next year 48 (October-November) he received dictatorship for the 2nd time, in 47. In the same year, after the victory over Pompey, during his absence he received a number of powers: in addition to the dictatorship - a consulate for 5 years (from 47) and tribunic power, that is, the right to sit together with the tribunes and carry out investigations with them - in addition, the right to name the people their candidate for magistracy, with the exception of the plebeians, the right to distribute provinces without drawing lots to former praetors [Provinces to former consuls are still distributed by the Senate.] and the right to declare war and make peace. Caesar's representative this year in Rome is his magister equitum - assistant to the dictator M. Antony, in whose hands, despite the existence of consuls, all power is concentrated.

In 46, Caesar was both dictator (from the end of April) for the third time and consul; Lepidus was the second consul and magister equitum. This year, after the African war, his powers are significantly expanded. He was elected dictator for 10 years and at the same time the leader of morals (praefectus morum), with unlimited powers. Moreover, he receives the right to be the first to vote in the Senate and occupy a special seat in it, between the seats of both consuls. At the same time, his right to recommend candidates for magistrates to the people was confirmed, which was tantamount to the right to appoint them.

In 45 he was dictator for the 4th time and at the same time consul; his assistant was the same Lepidus. After the Spanish War (January 44), he was elected dictator for life and consul for 10 years. He refused the latter, as, probably, the 5-year consulate of the previous year [In 45 he was elected consul at the suggestion of Lepidus.]. The immunity of the tribunes is added to the tribunician power; the right to appoint magistrates and pro-magistrates is extended by the right to appoint consuls, distribute provinces among proconsuls and appoint plebeian magistrates. In the same year, Caesar was given exclusive authority to dispose of the army and money of the state. Finally, in the same year 44, he was granted lifelong censorship and all his orders were approved in advance by the Senate and the people.

In this way, Caesar became a sovereign monarch, remaining within the limits of constitutional forms [For many of the extraordinary powers there were precedents in the past life of Rome: Sulla was already a dictator, Marius repeated the consulate, he ruled in the provinces through his agents Pompey, and more than once; Pompey was given by the people unlimited control over the funds of the state.] All aspects of the life of the state were concentrated in his hands. He disposed of the army and provinces through his agents - pro-magistrates appointed by him, who were made magistrates only on his recommendation. The movable and immovable property of the community was in his hands as a lifelong censor and by virtue of special powers. The Senate was finally removed from financial management. The activity of the tribunes was paralyzed by his participation in the meetings of their collegium and the tribunician power and tribunician sacrosanctitas granted to him. And yet he was not a colleague of the tribunes; having their power, he did not have their name. Since he recommended them to the people, he was the highest authority in relation to them. He disposes of the Senate arbitrarily both as its chairman (for which he mainly needed the consulate), and as the first to answer the question of the presiding officer: since the opinion of the almighty dictator was known, it is unlikely that any of the senators would dare to contradict him .

Finally, the spiritual life of Rome was in his hands, since already at the beginning of his career he was elected great pontiff and now the power of the censor and the leadership of morals were added to this. Caesar did not have special powers that would give him judicial power, but the consulate, the censorship, and the pontificate had judicial functions. Moreover, we also hear about constant court negotiations at Caesar’s home, mainly on issues of a political nature. Caesar sought to give the newly created power a new name: this was the honorary cry with which the army greeted the winner - imperator. Yu. Caesar put this name at the head of his name and title, replacing his personal name Guy with it. With this he gave expression not only to the breadth of his power, his imperium, but also to the fact that from now on he leaves the ranks of ordinary people, replacing his name with a designation of his power and at the same time eliminating from it the indication of belonging to one family: the head of state cannot be called like any other Roman S. Iulius Caesar - he is Imp(erator) Caesar p(ater) p(atriae) dict(ator) perp(etuus), as his title says in the inscriptions and on coins.

Foreign policy

The guiding idea of Caesar's foreign policy was the creation of a strong and integral state with natural borders, if possible. Caesar pursued this idea in the north, south, and east. His wars in Gaul, Germany and Britain were caused by his perceived need to push the border of Rome to the ocean on the one hand, and at least to the Rhine on the other. His plan for a campaign against the Getae and Dacians proves that the Danube border lay within the limits of his plans. Within the border that united Greece and Italy by land, Greco-Roman culture was to reign; the countries between the Danube and Italy and Greece were supposed to be the same buffer against the peoples of the north and east as the Gauls were against the Germans. Caesar's policy in the East is closely related to this. Death overtook him on the eve of the campaign to Parthia. His eastern policy, including the actual annexation of Egypt to the Roman state, was aimed at rounding out the Roman Empire in the East. The only serious opponent of Rome here were the Parthians: their affair with Crassus showed that they had in mind a broad expansionist policy. The revival of the Persian kingdom ran counter to the objectives of Rome, the successor to the monarchy of Alexander, and threatened to undermine the economic well-being of the state, which rested entirely on the monetary East. A decisive victory over the Parthians would have made Caesar, in the eyes of the East, the direct successor of Alexander the Great, the legitimate monarch. Finally, in Africa, Julius Caesar continued a purely colonial policy. Africa had no political significance: its economic importance, as a country capable of producing huge quantities of natural products, depended largely on regular administration, stopping the raids of nomadic tribes and re-establishing the best harbor in northern Africa, the natural center of the province and the central point for exchange with Italy - Carthage. The division of the country into two provinces satisfied the first two requests, the final restoration of Carthage satisfied the third.

Reforms of Julius Caesar