Sumerians: the most mysterious people in world history. Sumerian civilization Sumerian village river canals vegetation 2 huts

The country of Sumer gets its name from the people who settled around 3000 BC. in the lower reaches of the Euphrates River, near its confluence with the Persian Gulf. The Euphrates here is divided into numerous channels - branches, which either merge or diverge again. The banks of the river are low, so the Euphrates often changes its path to the sea. At the same time, the old riverbed gradually turns into a swamp. The clayey hills located at a distance from the river are severely scorched by the sun. The heat, heavy fumes from the swamps, and clouds of midges forced people to stay away from these places. The lower reaches of the Euphrates have long attracted the attention of farmers and pastoralists of Western Asia.

Small villages were located quite far away from water, since the Euphrates floods very violently and unexpectedly in the summer, and floods have always been very dangerous here. People tried not to enter the endless reed thickets, although very fertile lands were hidden underneath them. They were formed from silt that settled during floods. But in those days, people were still unable to cultivate these lands. They knew how to harvest crops only from small open areas, whose size resembled vegetable gardens rather than fields.

Everything changed when new, energetic owners appeared in the country of rivers and swamps - the Sumerians. In addition to fertile, but not yet developed lands, the new homeland of the Sumerians could boast a large amount of clay and reeds. There were no tall trees, no stone suitable for construction, no ores from which metals could be smelted. The Sumerians learned to build houses from clay bricks; the roofs of these houses were covered with reeds. Such a house had to be repaired every year, smearing the walls with clay so that it would not fall apart. Abandoned houses gradually turned into shapeless hills, as the bricks were made of unfired clay. The Sumerians often abandoned their homes when the Euphrates changed its course, and the settlement found itself far from the coast. There was a lot of clay everywhere, and within a couple of years the Sumerians managed to build a new village on the banks of the river that fed them. For fishing and river travel, the Sumerians used small round boats woven from reeds, coating them on the outside with resin.

Possessing fertile lands, the Sumerians eventually realized what high yields could be obtained if the swamps were drained and water was piped to dry areas. The flora of Mesopotamia is not rich, but the Sumerians acclimatized cereals, barley and wheat. Irrigation of fields in Mesopotamia was a difficult task. When too much water flowed through the canals, it seeped underground and connected with underground groundwater, which is salty in Mesopotamia. As a result, salt and water were again carried to the surface of the fields, and they quickly deteriorated; wheat did not grow on such lands at all, and rye and barley yielded low yields. The Sumerians did not immediately learn to determine how much water was needed to properly water the fields: excess or lack of moisture was equally bad. Therefore, the task of the first communities formed in the southern part of Mesopotamia was to establish an entire network of artificial irrigation. F. Engels wrote: “The first condition for agriculture here is artificial irrigation, and this is the business of either communities, or provinces, or the central government.”

The organization of large irrigation works, the development of ancient barter trade with neighboring countries and constant wars required the centralization of government administration.

Documents from the time of the existence of the Sumerian and Akkadian states mention a wide variety of irrigation works, such as regulating the overflow of rivers and canals, correcting damage caused by floods, strengthening banks, filling reservoirs, regulating the irrigation of fields and various earthworks associated with irrigating fields. Remains of ancient canals from the Sumerian era have been preserved to this day in some areas of southern Mesopotamia, for example, in the area of ancient Umma (modern Jokha). Judging by the inscriptions, these canals were so large that large boats, even ships loaded with grain, could navigate them. All these major works were organized by the state authorities.

Already in the fourth millennium BC. e. Ancient cities appeared on the territory of Sumer and Akkad, which were the economic, political and cultural centers of individual small states. In the southernmost part of the country was the city of Eridu, located on the shores of the Persian Gulf. The city of Ur was of great political importance, which, judging by the results of recent excavations, was the center of a strong state. The religious and cultural center of all of Sumer was the city of Nippur with its common Sumerian sanctuary, the temple of the god Enlil. Among other cities of Sumer, Lagash (Shirpurla), which waged a constant struggle with the neighboring Umma, and the city of Uruk, where, according to legend, the ancient Sumerian hero Gilgamesh once ruled, were of great political importance.

A variety of luxurious objects found in the ruins of Ur indicate a significant increase in technology, mainly metallurgy, at the beginning of the third millennium BC. e. During this era, they already knew how to make bronze by alloying copper with tin, learned to use meteorite iron, and achieved remarkable results in jewelry.

Periodic floods of the Tigris and Euphrates, caused by melting snow in the mountains of Armenia, had a certain significance for the development of agriculture based on artificial irrigation. Sumer, located in the south of Mesopotamia, and Akkad, which occupied the middle part of the country, were somewhat different from each other in climatic terms. In Sumer, winter was relatively mild, and the date palm could grow wild here. In terms of climatic conditions, Akkad is closer to Assyria, where snow falls in winter and the date palm does not grow wild.

The natural wealth of Southern and Central Mesopotamia is not great. The fatty and viscous clay of alluvial soil was an excellent raw material in the hands of the primitive potter. By mixing clay with asphalt, the inhabitants of ancient Mesopotamia made a special durable material, which replaced them with stone, rarely found in the southern part of Mesopotamia.

The flora of Mesopotamia is also not rich. The ancient population of this country acclimatized cereals, barley and wheat. The date palm and reed, which grew wild in the southern part of Mesopotamia, were of great importance in the economic life of the country. Obviously, the local plants included sesame (sesame), which was used for making oil, as well as tamarisk, from which sweet resin was extracted. The oldest inscriptions and images indicate that the inhabitants of Mesopotamia knew various breeds of wild and domestic animals. In the eastern mountains there were sheep (mouflons) and goats, and in the swampy thickets of the south there were wild pigs, which were tamed already in ancient times. The rivers were rich in fish and poultry. Various types of poultry were known in both Sumer and Akkad.

The natural conditions of Southern and Central Mesopotamia were favorable for the development of cattle breeding and agriculture, requiring the organization of economic life and the use of significant labor for a long time.

The Afro-Asian drought forced the fathers of the Sumerian civilization to move to the mouths of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and transform the swampy lowlands into the fertile land of the Middle Mesopotamia. The test that the fathers of the Sumerian civilization went through was preserved by the Sumerian legend. The slaying of the dragon Tiamat by the god Marduk and the creation of the world from his remains is an allegorical rethinking of the conquest of the primeval desert and the creation of the land of Shinar. The story of the Flood symbolizes the rebellion of Nature, rebelling against human intervention. The swamps formed in the territory of Lower Iraq between Amara on the Tigris, Nasiriyah on the Euphrates and Basra on the Shatt al-Arab have remained untouched from their origin to the present time, for not a single society has appeared on the historical stage that would like to and was able to master them. The swamp people who often visited these places passively adapted to them, but they never had sufficient potency to repeat the feat of the fathers of the Sumerian civilization, who lived in their immediate neighborhood some five or six thousand years ago. They didn't even try to transform the swamps into a network of canals and fields.

The monuments of the Sumerian civilization keep silent but precise evidence of those dynamic acts that, if we turn to Sumerian mythology, were performed by the god Marduk, who killed Tiamat.

When getting acquainted with the chapter, prepare messages: 1. About what contributed to the creation of the great powers - Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian (key words: iron, cavalry, siege technology, international trade). 2. About the cultural achievements of the ancient peoples of Western Asia, which remain important today (key words: laws, alphabet, Bible).

1. Country of two rivers. It lies between two large rivers - the Euphrates and the Tigris. Hence its name - Mesopotamia or Mesopotamia.

The soils in Southern Mesopotamia are surprisingly fertile. Just like the Nile in Egypt, the rivers gave life and prosperity to this warm country. But the river floods were violent: sometimes streams of water fell on villages and pastures, demolishing both dwellings and cattle pens. It was necessary to build embankments along the banks so that the flood would not wash away the crops in the fields. Canals were dug to irrigate fields and gardens. States arose here at approximately the same time as in the Nile Valley - more than five thousand years ago.

2. Cities made of clay bricks. The ancient people who created the first states in Mesopotamia were the Sumerians. Many settlements of the ancient Sumerians, growing, turned into cities - centers of small states. Cities usually stood on the banks of a river or near a canal. Residents sailed between them on boats woven from flexible branches and covered with leather. Of the many cities, the largest were Ur and Uruk.

In the Southern Mesopotamia there are no mountains or forests, which means there could be no construction made of stone and wood. Palaces, temples, living

old houses - everything here was built from large clay bricks. Wood was expensive - only rich houses had wooden doors; in poor houses the entrance was covered with a mat.

There was little fuel in Mesopotamia, and the bricks were not burned, but simply dried in the sun. Unfired brick crumbles easily, so the defensive city wall had to be made so thick that a cart could drive across the top.

3. Towers from earth to sky. Above the squat city buildings rose a stepped tower, the ledges of which rose to the sky. This is what the temple of the city's patron god looked like. In one city it was the Sun god Shamash, in another it was the Moon god San. Everyone revered the water god Ea - after all, he nourishes the fields with moisture, gives people bread and life. People turned to the goddess of fertility and love Ishtar with requests for rich grain harvests and the birth of children.

Only priests were allowed to climb to the top of the tower - to the sanctuary. Those who remained at the foot believed that the priests there were talking with the gods. On these towers, the priests monitored the movements of the heavenly gods: the Sun and the Moon. They compiled a calendar by calculating the timing of lunar eclipses. People's fortunes were predicted by the stars.

Scientist-priests also studied mathematics. They considered the number 60 sacred. Under the influence of the ancient inhabitants of Mesopotamia, we divide the hour into 60 minutes, and the circle into 360 degrees.

| Goddess Ishtar. Ancient statue. |

4. Writings on clay tablets. Excavation of the ancient cities of Mesopotamia, art

cheologists find tablets covered with wedge-shaped icons. These icons are pressed onto a soft clay tablet with the end of a specially pointed stick. To impart hardness, the inscribed tablets were usually fired in a kiln.

Wedge-shaped icons are a special script of Mesopotamia, cuneiform.

Each sign in cuneiform comes from a design and often represents a whole word, for example: star, leg, plow. But many signs expressing short monosyllabic words were also used to convey a combination of sounds or syllables. For example, the word “mountain” sounded like “kur” and the “mountain” icon also denoted the syllable “kur” - as in our puzzles.

There are several hundred characters in cuneiform, and learning to read and write in Mesopotamia was no less difficult than in Egypt. For many years it was necessary to attend the school of scribes. Lessons continued daily from sunrise to sunset. The boys diligently copied ancient myths and tales, the laws of kings, and the tablets of stargazers who read fortunes by the stars.

|

At the head of the school was a man who was respectfully called the “father of the school,” while the students were considered “sons of the school.” And one of the school workers was literally called “the man with the stick” - he monitored discipline.

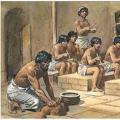

School in Mesopotamia. A drawing of our time.

Explain the meaning of the words: Sumerians, cuneiform, clay tablet, “father of the school,” “sons of the school.”

Test yourself. 1. Who owns the names Shamash, Sin, Ea, Ishtar? 2. What do the natural conditions of Egypt and Mesopotamia have in common? What are the differences? 3. Why were stepped towers erected in Southern Mesopotamia? 4. Why are there many more signs in cuneiform than in our alphabet of letters?

Describe the drawings of our time: 1. “Sumerian village” (see p. 66) - according to plan: 1) river, canals, vegetation; 2) huts and cattle pens; 3) main activities; 4) wheeled cart. 2. “School in Mesopotamia” (see p. 68) - according to plan: 1) students; 2) teacher; 3) a worker kneading clay.

Think about it. Why did rich people in Southern Mesopotamia indicate in their wills, among other property, a wooden stool and a door? Get acquainted with the documents - an excerpt from the tale of Gilgamesh and the myth of the flood (see pp. 69, 70). Why did the flood myth arise in Mesopotamia?

“Rivers of Eurasia” - Yangtze River. The most abundant river in the Russian Federation. Inland waters of Eurasia. It begins on the Valdai Hills and flows into the Caspian Sea, forming a delta. Lake Onega. Ladoga lake. Area – 17.7 thousand square meters. km, with islands of 18.1 thousand square meters. km. Ganges. Ganges (Ganga) is a river in India and Bangladesh. It begins on the Valdai Hills and flows into the Dnieper estuary of the Black Sea.

“River Geography” - Determine from the map which seas the Ob and Yenisei rivers flow into? What is a river? Determine on the map. Where do the rivers flow: Volga, Lena? River system. Let's check ourselves. DETERMINE WHICH RIVER BEGINS AT THE POINT WITH COORDINATES 57?N.L.33?E. Guess a riddle. Write the names of the rivers on the contour map. Change the letter “e” to “y” - I will become a satellite of the Earth.

“Success Channel” - How to solve the unsolvable. Ratings are given based on several parameters. A 35-minute interview between a recruiter and a real candidate for a real vacancy. In the final, the recruiter and experts give their verdict on whether the candidate is suitable for the position. Personnel decide. Channel propagation. New TV channel programs in 2011.

“Rivers 6th grade” - Where rivers look like leopards and jump from white peaks. Rivers - the main part of the land waters are lowland mountainous. Waters sushi Lesson of generalization and repetition 6th grade. L.N. Tolstoy. The fog lies on the steep slopes, motionless and deep. M.Yu. Lermontov. R. Gamzatov The Don waddles along in a peaceful, quiet flood. M.A. Sholokhov The river stretches out, flows, lazily sad And washes the banks.

“Grade 6 Geography of Rivers” - Rivers. Rivers in the works of poets. Amazon with Marañon (Southern parts of the river. Ob with Irtysh (Asia) 5451 km 6. Yellow River (Asia) 4845 km 7. Missouri (Northern Yangtze (Asia) 5800 km. The largest rivers in the world. Volga (Europe) 3531 km. Nile with Kagera (Africa) 6671 km "Oh, Volga!.. Mississippi with Missouri (North America) 6420 km America) 4740 km 8. Mekong (Asia) 4500 km 9. Amur with Argun (Asia) 4440 km . 10.

“River in Kazakhstan” - The ancient name is Ya?ik (from the Kazakh Aral Sea. The ecological situation in the Ural basin continues to remain tense. There are several reasons for such concern. 2003. Before the start of shallowing, the Aral Sea was the fourth largest lake in the world. By territory In Kazakhstan, the lakes are unevenly distributed.

Approximately 9 thousand years ago, humanity faced great changes.

For thousands of years, people foraged for food wherever they could find it. They hunted wild animals, collected fruits and berries, and looked for edible roots and nuts. If they were lucky, they managed to survive. Winters have always been a hungry time.

A permanent piece of land could not support many families, and people were scattered across the planet. 8 thousand years BC. e. There were probably no more than 8 million people living on the entire planet - about the same as in a modern large city.

Then, gradually, people learned to preserve food for future use. Instead of hunting animals and killing them on the spot, man learned to protect and care for them. In a special pen, the animals bred and multiplied.

Man killed them from time to time for food. So he received not only meat, but also milk, wool, and eggs. He even forced some of the animals to work for him.

In the same way, instead of collecting plant foods, man learned to plant and care for them, gaining confidence that the fruits of plants would be at hand when he needed them. Moreover, he could plant useful plants at a much higher density than he found them in the wild.

Hunters and gatherers turned into pastoralists and farmers. Those who were engaged in cattle breeding had to be on the move all the time.

Animals needed to be grazed, which meant finding fresh green pastures from time to time. Therefore, pastoralists became nomads, or nomads (from the Greek word meaning “pasture”).

Farming turned out to be more difficult. Sowing had to be done at the right time of year and in the right way. Plants had to be looked after, weeds had to be pulled out, animals that poisoned the crops had to be driven away. It was tedious and hard work, which lacked the carefree ease and changing landscapes of nomadic life. People who worked together all season had to remain in one place, because they could not leave the crops unattended.

Farmers lived in groups and built dwellings near their fields, which huddled together in order to protect themselves from wild animals and raids of nomads. This is how small towns began to appear.

Cultivation of plants, or agriculture, made it possible to feed many more people on a given piece of land than was possible with gathering, hunting, and even cattle breeding. The volume of food not only fed farmers after the harvest, but also allowed them to stock up on food for the winter.

It became possible to produce so much food that there was enough for the farmers, their families, and other people who did not work the land but provided the farmers with the things they needed.

Some people could devote themselves to making pottery, tools, creating jewelry from stone or metal, others became priests, others became soldiers, and all of them had to be fed by the farmer.

Villages grew, became large cities, and the society in such cities became complex enough to allow us to talk about “civilization” (the term itself comes from the Latin word meaning “big city”).

As the cultivation system spread and people learned to farm, the population began to grow and is still growing. In 1800 there were a hundred times more people on earth than before the invention of agriculture.

Now it is difficult to say exactly when agriculture got its start or how exactly it was discovered. Archaeologists, however, are quite sure that the general area of this epoch-making discovery was where the region we now call the Middle East lies - very likely somewhere around the modern border between Iran and Iraq.

Wheat and barley grew wild in this area, and it was these plants that were ideal for cultivation. They are easy to handle and can be made to grow thickly. The grain was ground into flour, which was stored for months without spoiling, and tasty and nutritious bread was baked from it.

In northern Iraq, for example, there is a place called Yarmo. It is a low hill that has been extensively excavated by American archaeologist Robert J. Braidwood since 1948. He discovered the remains of a very ancient village, and the foundations of the houses had thin walls made of compacted clay, and the house was divided into small rooms. These houses apparently accommodated between one hundred and three hundred people.

Very ancient traces of agriculture have been discovered. In the lowest, oldest layers, which arose 8 thousand years BC. e., they also found stone tools for harvesting barley and wheat, as well as stone vessels for water. Pottery made from baked clay was only excavated in higher layers. (Ceramics was a significant step forward, because in many areas clay is much more common than stone and is incomparably easier to work with.) The remains of domesticated animals have also been found. The early farmers of Yarmo had goats and perhaps dogs.

The yoke is located at the foot of a mountain range, where the air, rising, cools, the steam it contains condenses, and rain falls. This allowed ancient farmers to obtain rich harvests to feed their expanding population.

Life-giving rivers

However, at the foot of the mountains, where rain falls in abundance, the soil layer is thin and not very fertile. To the west and south of Yarmo lay flat, rich, fertile lands, excellently suitable for agricultural crops.

It was truly a fertile region.

This wide strip of excellent soil ran from what we now call the Persian Gulf, curving north and west, all the way to the Mediterranean Sea.

To the south it bordered the Arabian Desert (which was too dry, sandy and rocky for agriculture) in a huge crescent more than 1,600 km long. This area is commonly called the Fertile Crescent.

To become one of the richest and most populous centers of human civilization (which it eventually became), the Fertile Crescent needed regular, reliable rains, and this was precisely what was lacking. The country was flat, and warm winds swept over it, without dropping their cargo - moisture, until they reached the mountains bordering the Crescent on the east. Those rains that fell occurred in the winter; the summer was dry.

However, there was water in the country. In the mountains north of the Fertile Crescent, abundant snow served as an inexhaustible source of water that flowed down the mountain slopes into the lowlands of the south. The streams gathered into two rivers, which flowed more than 1,600 km in a southwestern direction, until they flowed into the Persian Gulf.

These rivers are known to us by the names that the Greeks gave them, thousands of years after the era of Yarmo. The eastern river is called the Tigris, the western is called the Euphrates.

The Greeks called the country between the rivers Mesopotamia, but they also used the name Mesopotamia.

Different areas of this region have been given different names throughout history, and none of them have become generally accepted throughout the country. Mesopotamia comes closest to this, and in this book I will use it not only to name the land between the rivers, but also for the entire region watered by them, from the mountains of Transcaucasia to the Persian Gulf.

This strip of land is approximately 1,300 km long and extends from northwest to southeast. “Upstream” always means “to the northwest,” and “downstream” always means “to the southeast.” Mesopotamia, by this definition, covers an area of about 340 thousand square meters. km and is close in shape and size to Italy.

Mesopotamia includes the upper bend of the arc and the eastern part of the Fertile Crescent. The western part, which is not part of Mesopotamia, in later times became known as Syria and included the ancient country of Canaan.

Most of Mesopotamia is now included in the country called Iraq, but its northern regions overlap the borders of this country and belong to modern Turkey, Syria, Iran and Armenia.

Yarmo lies only 200 km east of the Tigris River, so we can assume that the village was located on the northeastern border of Mesopotamia. It is easy to imagine that the technique of cultivating the land must have spread westward, and by 5000 BC. e. agriculture was already practiced in the upper reaches of both large rivers and their tributaries. The technique of cultivating the land was brought not only from Yarmo, but also from other settlements located along the mountainous border. In the north and east, improved varieties of grains were grown and cattle and sheep were domesticated. Rivers were more convenient than rain as a source of water, and the villages that grew on their banks became larger and richer than Yarmo. Some of them occupied 2–3 hectares of land.

The villages, like Yarmo, were built from unfired clay bricks. This was natural, because in most of Mesopotamia there is no stone or timber, but clay is available in abundance. The lowlands were warmer than the hills around Jarmo, and early river houses were built with thick walls and few openings to keep the heat out of the house.

Of course, there was no waste collection system in the ancient settlements. Garbage gradually accumulated on the streets and was compacted by people and animals.

The streets became higher, and the floors in houses had to be raised, laying new layers of clay.

Sometimes buildings made of sun-dried bricks were destroyed by storms and washed away by floods. Sometimes the entire town was demolished. The surviving or newly arrived residents had to rebuild it right from the ruins. As a result, the towns, built again and again, ended up standing on mounds that rose above the surrounding fields. This had some advantages - the city was better protected from enemies and from floods.

Over time, the city was completely destroyed, and only a hill (“tell” in Arabic) remained. Careful archaeological excavations on these hills revealed habitable layers one after another, and the deeper the archaeologists dug, the more primitive the traces of life became. This is clearly visible in Yarmo, for example.

The hill of Tell Hassun, on the upper Tigris, about 100 km west of Yarmo, was excavated in 1943. Its oldest layers contain painted pottery more advanced than any findings from ancient Yarmo. It is believed to represent the Hassun-Samarran period of Mesopotamian history, which lasted from 5000 to 4500 BC. e.

The hill of Tell Halaf, about 200 km upstream, reveals the remains of a town with cobblestone streets and more advanced brick houses. During the Khalaf period, from 4500 to 4000 BC. e., ancient Mesopotamian ceramics reaches its highest development.

As Mesopotamian culture developed, techniques for using river water improved. If you leave the river in its natural state, you can only use fields located directly on the banks.

This sharply limited the area of usable land. Moreover, the volume of snowfall in the northern mountains, as well as the rate of snowmelt, vary from year to year. There were always floods at the beginning of summer, and if they were stronger than usual, there was too much water, while in other years there was too little.

People figured out that a whole network of trenches or ditches could be dug on both banks of the river. They diverted water from the river and brought it to each field through a fine network. Canals could be dug along the river for kilometers, so that fields far from the river still ended up on the banks. Moreover, the banks of canals and rivers themselves could be raised with the help of dams, which water could not overcome during floods, except in places where it was desirable.

In this way it was possible to count on the fact that, generally speaking, there would be neither too much nor too little water. Of course, if the water level fell unusually low, the canals, except those located near the river itself, were useless. And if the floods were too powerful, the water would flood the dams or destroy them. But such years were rare.

The most regular water supply was in the lower reaches of the Euphrates, where seasonal and annual fluctuations in level are less than on the turbulent Tigris River. Around 5000 BC e. in the upper reaches of the Euphrates, a complex irrigation system began to be built, it spread down and by 4000 BC. e. reached the most favorable lower Euphrates.

It was on the lower reaches of the Euphrates that civilization flourished. Cities became much larger, and in some by 4000 BC. e. the population reached 10 thousand people.

Such cities became too large for the old tribal systems, where everyone lived as one family, obeying its patriarchal head. Instead, people without clear family ties had to settle together and cooperate peacefully in their work. The alternative would be starvation. To maintain peace and enforce cooperation, a leader had to be elected.

Each city then became a political community, controlling the agricultural land in its vicinity in order to feed the population.

City-states arose, and each city-state was headed by a king.

The inhabitants of the Mesopotamian city-states essentially did not know where the much-needed river water came from; why floods occur in one season and not another; why in some years they do not exist, while in others they reach disastrous heights. It seemed reasonable to explain all this as the work of beings much more powerful than ordinary people - the gods.

Since it was believed that fluctuations in water levels did not follow any system, but were completely arbitrary, it was easy to assume that the gods were hot-tempered and capricious, like extremely strong overgrown children. In order for them to give as much water as needed, they had to be cajoled, persuaded when they were angry, and kept in a good mood when they were peaceful. Rituals were invented in which the gods were endlessly praised and tried to appease.

It was assumed that the gods liked the same things that people liked, so the most important method of appeasing the gods was to feed them. It is true that the gods do not eat like men, but the smoke from the burning food rose to the sky, where the gods were imagined to live, and animals were sacrificed to them by burning.

An ancient Mesopotamian poem describes a great flood sent by the gods that destroys humanity. But the gods, deprived of sacrifices, became hungry. When a righteous survivor of the flood sacrifices animals, the gods gather around impatiently:

The gods smelled it

The gods smelled a delicious smell,

The gods, like flies, gathered over the victim.

Naturally, the rules of communication with the gods were even more complex and confusing than the rules of communication between people. A mistake in communicating with a person could lead to murder or bloody feud, but a mistake in communicating with God could mean famine or a flood that devastates the entire area.

Therefore, in agricultural communities a powerful priesthood grew up, much more developed than that which can be found in hunting or nomadic societies. The kings of the Mesopotamian cities were also high priests and offered sacrifices. The center around which the entire city revolved was the temple. The priests who occupied the temple were responsible not only for the relationship between people and gods, but also for the management of the city itself. They were treasurers, tax collectors, organizers - the bureaucracy, the bureaucracy, the brain and heart of the city.

Great inventions

Irrigation did not solve everything. A civilization based on irrigated agriculture also had its problems. For example, river water that flows over the surface of the soil and filters through it contains more salt than rainwater. Over centuries of irrigation, salt gradually accumulates in the soil and destroys it unless special flushing methods are used.

Some irrigation civilizations relapsed into barbarism for precisely this reason. Mesopotamia avoided this. But the soil gradually became saline. This, by the way, was one of the reasons that the main crop was (and remains to this day) barley, which tolerates slightly saline soil well.

Moreover, it must be said that accumulated food, tools, metal jewelry and, in general, all valuable things are a constant temptation for neighboring peoples who do not have agriculture. Therefore, the history of Mesopotamia was a long series of ups and downs. At first, civilization is built in peace, accumulating wealth. Then nomads come from abroad, overturn civilization and push it down. There is a decline in material culture and even a “dark age.”

However, these newcomers learn a civilized life, and the material situation rises again, often reaching new heights, but only to be again defeated by a new invasion of barbarians. This happened again and again.

Mesopotamia was bordered by strangers on two flanks. Severe mountaineers lived in the north and northeast. In the south and southwest there are equally harsh sons of the desert. From one flank or the other, Mesopotamia was doomed to await invasion, and possibly disaster.

So, around 4000 BC. e. The Khalaf period came to an end, for nomads attacked Mesopotamia from the Zagr mountain range, which borders the Mesopotamian lowland from the northeast.

The culture of the following period can be studied at Tell al-Ubaid, a mound on the lower reaches of the Euphrates. The finds, as might be expected, largely reflect a decline in comparison with the works of the Halaf period. The Ubaid period probably lasted from 4000 to 3300 BC. e.

The nomads who built the culture of the Ubaid period may well have been the people we call the Sumerians. They settled along the lower reaches of the Euphrates, and this area of Mesopotamia in this historical period is usually called Sumer or Sumeria.

The Sumerians found in their new home an already established civilization, with cities and a developed canal system. Once they had mastered a civilized way of life, they began to fight to return to the level of civilization that existed before their destructive invasion.

Then, surprisingly, in the last centuries of the Ubaid period they rose above their previous level. Over these centuries, they introduced a number of important inventions that we use to this day.

They developed the art of building monumental structures.

Having descended from the mountains, where there was enough rain, they retained the concept of gods living in the sky. Feeling the need to get closer to the heavenly gods in order for the rituals to be most effective, they built flat-topped pyramids from baked bricks and made sacrifices on the tops. They soon realized that on the flat top of the first pyramid they could build a second, smaller one, on the second - a third, etc.

Such stepped structures are known as ziggurats, which were probably the most impressive structures of their time. Even the Egyptian pyramids appeared only centuries after the first ziggurats.

However, the tragedy of the Sumerians (and other Mesopotamian peoples who succeeded them) was that they could only work with clay, while the Egyptians had granite. The Egyptian monuments for the most part still stand, causing the wonder of all subsequent centuries, and nothing remains of the Mesopotamian monuments.

Information about ziggurats reached the modern West through the Bible. The Book of Genesis (which reached its present form twenty-five centuries after the end of the Ubaid period) tells us of ancient times when people “found a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there” (Gen. 11:2). “Land of Shinar” is, of course, Sumer. Having settled there, the Bible continues, they said: “Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower, the top of which will reach to heaven” (Gen. 11:4).

This is the famous "Tower of Babel", the legend of which is based on the ziggurats.

Of course, the Sumerians tried to reach the sky because they hoped that sacred rites would be more effective on top of ziggurats than on earth.

Modern Bible readers, however, usually think that the tower builders were actually trying to reach heaven.

The Sumerians must have also used ziggurats for astronomical observations, since the movements of celestial bodies can be interpreted as important indications of the gods' intentions. They were the first astronomers and astrologers.

Astronomical works led them to the development of mathematics and the calendar.

Much of what they came up with more than 5 thousand years ago remains with us to this day. It was the Sumerians, for example, who divided the year into twelve months, the day into twenty-four hours, the hour into sixty minutes and the minute into sixty seconds.

They may also have invented the seven-day week.

They also developed a complex system of trade and commercial settlements.

To facilitate trade, they developed a complex system of weights and measures and invented a postal system.

They also invented the wheeled carriage. Previously, heavy loads were moved on rollers. The rollers remained behind as they moved, and they again had to be moved forward. It was slow and tedious work, but it was still easier than dragging a load along the ground using brute force.

When a platform had a pair of wheels on an axle attached to it, it meant two permanent rollers moving with it. A wheeled cart with a single donkey now made it possible to transport loads that previously required the efforts of a dozen men. It was a revolution in transport, equivalent to the invention of railways in modern times.

Greatest invention

The main cities of Sumer during the Ubaid period were Eridu and Nippur.

Eridu, perhaps the oldest settlement in the south, dating back to approximately 5300 BC. e., was located on the shores of the Persian Gulf, probably at the mouth of the Euphrates. Now its ruins are located 16 km south of the Euphrates, for over the millennia the river has changed its course many times.

The ruins of Eridu are even further away from the Persian Gulf today. In the early period from Sumer, the Persian Gulf extended to the northwest further than it does now, and the Tigris and Euphrates flowed into it at separate mouths, spaced 130 km from each other.

Both rivers brought silt and humus from the mountains and deposited them at their mouths, creating a lowland with rich soil that slowly moved southeast, filling the upper part of the bay.

Flowing through the newly reclaimed lands, the rivers gradually came closer together until they merged into one, forming a single channel flowing into the Persian Gulf, the shores of which today have moved to the southeast almost 200 km further than in the heyday of Eridu.

Nippur was located 160 km from Eridu, upstream. Its ruins are also now far from the banks of the capricious Euphrates, which currently flows 30 km to the west.

Nippur remained the religious center of the Sumerian city-states long after the end of the Ubaid period, even ceasing to be one of the largest and most powerful cities. Religion is a more conservative thing than any other aspect of human life. The city could become a religious center at first because it was the capital. It could then lose its importance, shrink in size and population, and even fall under the control of conquerors, while still remaining a revered religious center. It is enough to remember the importance of Jerusalem in those centuries when it was just a dilapidated village.

As the Ubaid period moved towards its conclusion, the conditions were ripe for the greatest of all inventions, the most important in the civilized history of mankind - the invention of writing.

One of the factors that led the Sumerians in this direction must have been the clay they used in construction. The Sumerians could not help but notice that soft clay easily took on imprints, which remained even after it was fired and hardened into brick. Therefore, the craftsmen could well have thought of making marks deliberately, like a signature on their own work. To prevent “counterfeits,” they could come up with raised stamps that could be imprinted on the clay in the form of a picture or design that served as a signature.

The next step was taken in the city of Uruk, located 80 km upstream from Eridu. Uruk achieved dominance towards the end of the Ubaid period, and the next two centuries, from 3300 to 3100, are called the Uruk period. Perhaps Uruk became active and prosperous precisely because new inventions were made there, or, conversely, inventions appeared because Uruk became active and prosperous. Today it is difficult to distinguish between the cause and effect of this process.

At Uruk, raised stamps were replaced by cylinder seals. The seal was a small stone cylinder on which some scene was carved in deep relief. The cylinder could be rolled over clay, producing an imprint that could be repeated over and over again at will.

Such cylinder seals multiplied in subsequent Mesopotamian history and clearly represented not only means of signature, but also works of art.

Another impetus for the invention of writing was the need for accounting.

Temples were central warehouses for grain and other things, and there were pens for livestock. They contained a surplus, which was spent on sacrifices to the gods, on food during periods of famine, for military needs, etc. The priests had to know what they had, what they received and what they gave.

The simplest way to keep track is to make marks, such as notches on a stick.

The Sumerians had trouble with sticks, but seals suggested that clay could be used. So they began to make prints of different types for units, for tens, for six tens. The clay tablet containing the credentials could be fired and kept as a permanent record.

To show whether a given combination of marks referred to cattle or to measures of barley, the priests could make a rough image of a bull's head on one tablet, and an image of a grain or ear on another. People realized that a certain mark could represent a certain object. Such a mark is called a pictogram (“picture writing”), and if people agreed that the same set of pictograms meant the same thing, they were able to communicate with each other without the help of speech and the messages could be stored permanently.

Little by little, they agreed on the badges - perhaps already by 3400 AD. e. Then they came up with the idea that abstract ideas can be expressed in ideograms (“conceptual writing”). Thus, the circle with rays could represent the Sun, but it could also represent light. A rough mouth design could mean hunger, but it could also just mean a mouth. Together with the crude image of an ear of corn, it could mean food.

As time went on, the icons became more and more sketchy and less and less like the objects they originally depicted. For the sake of speed, scribes switched to making badges by pressing a sharp tool into soft clay so that a narrow triangular dent, similar to a wedge, was obtained. We now call the signs that began to be built from these marks cuneiform.

By the end of the Uruk period, by 3100 BC. BC, the Sumerians had a fully developed written language - the first in the world. The Egyptians, whose villages dotted the banks of the Nile River in northeast Africa, 1,500 kilometers west of the Sumerian cities, heard about the new system. They borrowed the idea but improved it in some ways. They used papyrus for writing, sheets made from river reed fibers that took up much less space and were much easier to work with. They covered papyrus with symbols much more attractive than the crude cuneiform writing of the Sumerians.

Egyptian symbols were carved into stone monuments and painted on the interior walls of tombs. They were preserved in plain sight, while the cuneiform-covered bricks remained hidden underground. This is why it has long been thought that the Egyptians were the first to invent writing. Now, however, this honor has been returned to the Sumerians.

The establishment of writing in Sumer meant revolutionary changes in the social system. It further strengthened the power of the priests, for they knew the secret of writing and knew how to read records, but ordinary people did not know how to do this.

The reason was that learning to write was not an easy task. The Sumerians never rose above the concept of separate symbols for each basic word, and arrived at 2 thousand ideograms. This presented serious difficulties for memorization.

Of course, it was possible to break words down into simple sounds and represent each of those sounds with a separate icon. It is enough to have two dozen such sound icons (letters) to form any conceivable word. However, such a system of letters, or alphabet, was not developed until many centuries after the Sumerian invention of writing, and then by the Canaanites, who lived at the western end of the Fertile Crescent, and not by the Sumerians.

Writing also strengthened the power of the king, for he could now express his own view of things in writing and carve it on the walls of stone buildings along with carved scenes. It was difficult for the opposition to compete with this ancient written propaganda.

And the merchants felt relief. It became possible to keep contracts certified by priests in writing, and to record laws. When the rules governing society became permanent, rather than hidden in the unreliable memories of leaders, when those rules could be dealt with by those affected by them, society became more stable and orderly.

Writing was probably first established in Uruk, as evidenced by the ancient inscriptions found today in the ruins of this city. The prosperity and power that came with the rise of trade, followed by the advent of writing, contributed to the growth of the size and splendor of the city. By 3100 BC. e. it has become the most perfect city in the world, covering an area of more than 5 square meters. km. The city had a temple 78 m long, 30 m wide and 12 m high - probably the largest building in the world at that time.

Sumer as a whole, blessed with writing, quickly became the most developed region of Mesopotamia. The countries upstream, in fact with a more ancient civilization, fell behind and were forced to submit to the political and economic dominance of the Sumerian kings.

One of the important consequences of writing was that it allowed people to maintain long and detailed records of events that could be passed down from generation to generation with only minor distortions. Lists of the names of kings, stories of rebellions, battles, conquests, natural disasters experienced and overcome, even boring statistics of temple reserves or tax archives - all this tells us infinitely more than can be learned from a simple study of surviving pottery or tools. It is from written records that we get what we call history. Everything that existed before writing belongs to the prehistoric era.

We can therefore say that along with writing, the Sumerians invented history.

Flood

The period from 3100 to 2800 BC. e. called the period of proto-literacy or early writing. Sumer prospered. One might assume that since writing already existed, we should know a lot about this period. But that's not true.

It's not that the language is unclear. The Sumerian language was deciphered in the 1930s and 40s. XX century (thanks to some coincidence, which I will return to later) by Russian-American archaeologist Samuel Kramer.

The difficulty is that records before 2800 are poorly preserved. Even people who lived after 2800 seemed to lack records relating to the previous period. At least the later records that describe events before this key date seem to be of an absolutely fantastic nature.

The reason can be explained in one word - flood. Those Sumerian documents that reflect a mythological view of history always refer to the period “before the flood.”

In terms of river floods, the Sumerians were less fortunate than the Egyptians. The Nile, the great Egyptian river, floods every year, but the height of the flood varies within small limits. The Nile begins in the great lakes of eastern central Africa, and they act as giant reservoirs that moderate flood fluctuations.

The Tigris and Euphrates begin not in lakes, but in mountain streams. There are no reservoirs. In years when there is a lot of snow in the mountains, and spring heat waves come suddenly, the flood reaches catastrophic heights (in 1954, Iraq was heavily damaged by flooding).

Between 1929 and 1934, the English archaeologist Sir Charles Leonard Woolley excavated the hill where the ancient Sumerian city of Ur was hidden. It was located near the old mouth of the Euphrates, just 16 km east of Eridu. There he discovered a layer of silt more than three meters thick, devoid of any cultural remains.

He decided that before him were the deposits of a gigantic flood. According to his estimates, water 7.5 m deep covered an area almost 500 km long and 160 km wide - almost the entire land of the interfluve.

The flood, however, may not have been so catastrophically disastrous. The flood may have destroyed some cities and spared others, for the levees of one city may have been neglected, while in another they may have been maintained by the heroic and incessant efforts of the townspeople. So, in Eridu there is not such a thick layer of silt as in Ur. In some other cities, thick layers of silt were deposited at a different time than in Ur.

However, there must have been one Flood that was worse than any other. Perhaps it was he who buried Ur, at least for a while. Even if it did not completely destroy other cities, the economic decline resulting from the partial destruction of cultivated lands plunged Sumer into a period of “dark ages,” albeit a short one.

This superflood, or Flood (we can capitalize it), took place around 2800 BC. e. The flood and subsequent chaos could practically destroy the city archives. Subsequent generations could only try to reconstruct history based on memories of previous records.

Perhaps storytellers over time took the opportunity to build legends from the fragmentary memories they had of names and events, and thus replace boring history with exciting storytelling.

For example, the kings who are noted in later records as "reigning before the Flood" reigned for absurdly long periods. Ten such kings are listed, and each of them allegedly reigned for tens of thousands of years.

We find traces of this in the Bible, for the early chapters of Genesis appear to be based in part on a Mesopotamian legend. Thus, the Bible lists ten patriarchs (from Adam to Noah) who lived before the Flood. The biblical authors, however, did not believe the long reigns of the Sumerians (or those who followed them); they limited the age of the antediluvian patriarchs to less than one thousand years.

The longest living person in the Bible was Methuselah, the eighth of the patriarchs, and he reportedly lived “only” nine hundred and sixty-nine years.

The Sumerian Flood legend grew into the world's first epic narrative known to us. Our most complete version dates back more than two thousand years after the Flood, but fragments of older tales also survive, and a significant part of the epic can be reconstructed.

His hero, Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, lived some time after the Flood.

He possessed heroic courage and performed glorious deeds. The adventures of Gilgamesh sometimes make it possible to call him the Sumerian Hercules. It is even possible that the legend (which became very popular in subsequent centuries and was to spread throughout the ancient world) influenced the Greek myths of Hercules and some episodes of the Odyssey.

When Gilgamesh's close friend died, the hero decided to avoid such a fate and went in search of the secret of eternal life. After a complex search, enlivened by many episodes, he finds Utnapishtim, who during the Flood built a large ship and escaped with his family on it. (It was he who, after the Flood, made the sacrifice that the hungry gods liked so much.) The Flood is depicted here as a world event, which in its effect was such, because for the Sumerians Mesopotamia constituted almost the entire world, which was taken into account.

Utnapishtim not only survived the Flood, but also received the gift of eternal life. He directs Gilgamesh to the place where a certain magical plant grows. If he eats this plant, he will retain his youth forever. Gilgamesh finds the plant, but does not have time to eat it, because the plant is stolen by a snake. (Snakes, due to their ability to shed old, worn skin and appear shiny and new, had, according to many ancients, the ability to rejuvenate, and the epic of Gilgamesh, among other things, explains this.) The story of Utnapishtim is so similar to the biblical story of Noah which most historians suspect is borrowed from the story of Gilgamesh.

It is also possible that the serpent that seduced Adam and Eve and deprived them of the gift of eternal life was descended from the serpent that deprived Gilgamesh of the same thing.

Wars

The flood was not the only disaster that the Sumerians had to face. There were also wars.

There are indications that in the first centuries of the Sumerian civilization, the cities were separated by strips of uncultivated land, and their populations had little contact with each other. There might even have been some mutual sympathy, a feeling that the great enemy to be defeated was the capricious river and that they were all fighting this enemy together.

However, even before the Flood, the expanding city-states would swallow up the empty lands in between. Three hundred kilometers of the lower reaches of the Euphrates were gradually covered with cultivated land, and the pressure of a growing population forced each city to wedge itself as far as possible into the territory of its neighbor.

Under similar conditions, the Egyptians formed a single state and lived in peace for centuries - the entire era of the Old Kingdom. The Egyptians, however, lived in isolation, protected by the sea, the desert and the Nile rapids. They had little reason to cultivate the art of war.

The Sumerians, on the contrary, open on both sides to the devastating raids of nomads, had to create armies. And they created them. Their soldiers marched in orderly ranks, with donkeys pulling carts of supplies behind them.

But once an army has been created to repel the nomads, there is a strong temptation to use it to good effect in the intervals between raids. Each side in the border disputes was now ready to support its views with an army.

Before the Flood, wars were probably not particularly bloody. The main weapons were wooden spears and arrows with stone tips. The tips could not be made very sharp; they cracked and pricked when colliding with an obstacle. Leather-covered shields were probably more than enough against such weapons, and in a typical battle there would be a lot of hitting and a lot of sweat, but, given the above factors, few casualties.

Around 3500 BC BC, however, methods for smelting copper were discovered, and by 3000 it was discovered that if copper and tin were mixed in certain proportions, an alloy was formed, which we call bronze. Bronze is a hard alloy suitable for sharp blades and thin points. Moreover, a dull blade could easily be sharpened again.

Bronze had not yet become widespread even by the time of the Flood, but it was enough to change the balance in the constant struggle between nomads and farmers forever in favor of the latter. To obtain bronze weapons, it was necessary to have advanced technology that far exceeded the capabilities of simple nomads. Until the time the nomads were able to arm themselves with their own bronze weapons or learn ways to compensate for their lack, the advantage remained with the townspeople.

Unfortunately, starting from 3000 BC. e. the Sumerian city-states used bronze weapons against each other too, so the cost of war increased (as it has increased many times since). As a result, all cities were weakened, for not one of them could completely defeat its neighbors.

If the history of other better known city-states (such as those of ancient Greece) is anything to go by, weaker cities would always unite against any city that seemed to come close enough to defeating all the others.

We can assume that partly due to chronic warfare and the waste of human energy, the dam and canal systems fell into disrepair. Perhaps this is why the Flood was so enormous and caused such damage.

Yet even in the period of disorganization that followed the Flood, the superiority of bronze weapons was supposed to keep Sumer safe from nomads. For at least another century after the Flood, the Sumerians remained in power.

Over time, the country fully recovered from the disaster and became more prosperous than ever before. Sumer in this era consisted of about thirteen city-states, dividing among themselves 26 thousand square meters. km of cultivated land.

The cities, however, did not learn the lessons of the Flood. The restoration was over, and the tedious series of endless wars began all over again.

According to the records we have, the most important among the Sumerian cities in the period immediately after the Flood was Kish, which lay on the Euphrates about 240 km above Ur.

Although Kish was a fairly ancient city, before the Flood it did not stand out as anything unusual. Its sudden rise after the disaster makes it seem that the great cities of the south were put out of action for a time.

Kish's reign was short-lived, but as the first city to rule after the Flood (and therefore the first city to rule in the period of reliable historical records), it achieved very high prestige. In later centuries, the conquering Sumerian kings called themselves "Kings of Kish" to show that they ruled all of Sumer, although Kish had by then lost its importance. (This is reminiscent of the Middle Ages, when German kings styled themselves “Roman Emperors,” although Rome had long since fallen.) Kish lost, for the cities downstream finally recovered. They were rebuilt, they once again gathered their strength and regained their traditional role. The lists of Sumerian kings that we have list the kings of individual states in related groups, which we call dynasties.

Thus, during the “first dynasty of Uruk,” this city took the place of Kish and for some time remained as dominant as before. The fifth king of this first dynasty was none other than Gilgamesh, who reigned around 2700 BC. e. and supplied the famous epic with a grain of truth, around which mountains of fantasies were heaped. By 2650 BC. e. Ur regained leadership under its own first dynasty.

A century later, around 2550 BC. e., the name of the conqueror emerges. This is Eannatum, king of Lagash, a city located 64 km east of Uruk.

Eannatum defeated both armies - Uruk and Ur. At least that's what he claims on the stone columns that he installed and decorated with inscriptions. (Such columns are called "steles" in Greek.) Such inscriptions cannot always be fully trusted, of course, for they are the ancient equivalent of modern military communiqués and often exaggerate successes - out of vanity or to maintain morale.

The most impressive of the steles erected by Eannatum shows a closed formation of warriors with helmets and spears at the ready, walking over the bodies of defeated enemies. Dogs and kites devour the bodies of the dead. This monument is called the Stele of the Korshunov.

The stela commemorates Eannatum's victory over the city of Umma, 30 km west of Lagash. The inscription on the stele states that the Umma was the first to start the war by stealing the boundary stones, but, however, there has never been an official account of the war that did not blame the enemy for its outbreak. And we do not have the report of the Ummah.

For a century after the reign of Eannatum, Lagash remained the strongest of the Sumerian cities. It was full of luxury and beautiful metalwork was discovered in its ruins. He controlled about 4,700 sq. km of land - a huge territory at that time.

The last ruler of the first dynasty of Lagash was Urukagina, who ascended the throne around 2415 BC. e.

He was an enlightened king about whom we can only wish we knew more. Apparently he felt that there was, or should have been, a feeling of kinship among all the Sumerians, for the inscription he left contrasts the civilized city dwellers with the barbarian tribes of strangers. Perhaps he sought to create a united Sumer, a fortress impregnable to nomads, where the people could develop in peace and prosperity.

Urukagina was also a social reformer, for he tried to limit the power of the priesthood. The invention of writing placed such power in the hands of the priests that they became positively dangerous for further development. So much wealth fell into their hands that the remainder was not enough for the economic growth of the city.

Unfortunately, Urukagina suffered the fate of many reformer kings. His motives were good, but the real power was retained by conservative elements. Even the common people whom the king tried to help seemed to fear the priests and gods more than they wanted their own good.

Moreover, the priests, putting their own interests above the interests of the city, did not hesitate to come to terms with the rulers of other cities that had been under the domination of Lagash for a century and were more than willing to try to achieve dominance in their turn.

The city of Umma, crushed by Eannatum, now had a chance for revenge.

It was ruled by Lugalzaggesi, a capable warrior who slowly increased his strength and possessions while Urukagina was busy with reforms in Lagash.

Lugalzaggesi captured Ur and Uruk and established himself on the throne of Uruk.

Using Uruk as a base, Lugalzaggesi around 2400 AD. e. attacked Lagash, defeated his demoralized army and plundered the city. He remained the sovereign ruler of all of Sumer.

No Sumerian had ever achieved such military success. According to his own boastful inscriptions, he sent armies as far north and west as the Mediterranean Sea. The population density of Mesopotamia was now ten times higher than in non-agricultural regions. In a number of Sumerian cities, such as Umma and Lagash, the population reached 10–15 thousand people.

Notes:

After 1800, the so-called “industrial revolution” began to spread throughout the world, allowing humanity to multiply at a rate not possible with pre-industrial agriculture alone—but that is another story, beyond the scope of this book. (Note by author)

The idea that the gods lived in the sky may have stemmed from the fact that the earliest farmers depended on rain falling from the sky rather than on river floods. (Note by author)

However, at the foot of the mountains, where rain falls in abundance, the soil layer is thin and not very fertile. To the west and south of Yarmo lay flat, rich, fertile lands, excellently suitable for agricultural crops. It was truly a fertile region.This wide strip of excellent soil ran from what we now call the Persian Gulf, curving north and west, all the way to the Mediterranean Sea. To the south it bordered the Arabian Desert (which was too dry, sandy and rocky for agriculture) in a huge crescent more than 1,600 km long. This area is commonly called the Fertile Crescent.

To become one of the richest and most populous centers of human civilization (which it eventually became), the Fertile Crescent needed regular, reliable rains, and this was precisely what was lacking. The country was flat, and warm winds swept over it, without dropping their cargo - moisture, until they reached the mountains bordering the Crescent on the east. Those rains that fell occurred in the winter; the summer was dry.

However, there was water in the country. In the mountains north of the Fertile Crescent, abundant snow served as an inexhaustible source of water that flowed down the mountain slopes into the lowlands of the south. The streams gathered into two rivers, which flowed more than 1,600 km in a southwestern direction, until they flowed into the Persian Gulf.

These rivers are known to us by the names that the Greeks gave them, thousands of years after the era of Yarmo. The eastern river is called the Tigris, the western - the Euphrates. The Greeks called the country between the rivers Mesopotamia, but they also used the name Mesopotamia.

Different areas of this region have been given different names throughout history, and none of them have become generally accepted throughout the country. Mesopotamia comes closest to this, and in this book I will use it not only to name the land between the rivers, but also for the entire region watered by them, from the mountains of Transcaucasia to the Persian Gulf.

This strip of land is approximately 1,300 km long and extends from northwest to southeast. "Upstream" always means "towards the northwest", and "downstream" always means "towards the southeast". Mesopotamia, by this definition, covers an area of about 340 thousand square meters. km and is close in shape and size to Italy.

Mesopotamia includes the upper bend of the arc and the eastern part of the Fertile Crescent. The western part, which is not part of Mesopotamia, in later times became known as Syria and included the ancient country of Canaan.

Most of Mesopotamia is now included in the country called Iraq, but its northern regions overlap the borders of this country and belong to modern Turkey, Syria, Iran and Armenia.

Yarmo lies only 200 km east of the Tigris River, so we can assume that the village was located on the northeastern border of Mesopotamia. It is easy to imagine that the technique of cultivating the land must have spread westward, and by 5000 BC. e. agriculture was already practiced in the upper reaches of both large rivers and their tributaries. The technique of cultivating the land was brought not only from Yarmo, but also from other settlements located along the mountainous border. In the north and east, improved varieties of grains were grown and cattle and sheep were domesticated. Rivers were more convenient than rain as a source of water, and the villages that grew on their banks became larger and richer than Yarmo. Some of them occupied 2 - 3 hectares of land.

The villages, like Yarmo, were built from unfired clay bricks. This was natural, because in most of Mesopotamia there is no stone or timber, but clay is available in abundance. The lowlands were warmer than the hills around Jarmo, and early river houses were built with thick walls and few openings to keep the heat out of the house.

Of course, there was no waste collection system in the ancient settlements. Garbage gradually accumulated on the streets and was compacted by people and animals. The streets became higher, and the floors in houses had to be raised, laying new layers of clay.

Sometimes buildings made of sun-dried bricks were destroyed by storms and washed away by floods. Sometimes the entire town was demolished. The surviving or newly arrived residents had to rebuild it right from the ruins. As a result, the towns, built again and again, ended up standing on mounds that rose above the surrounding fields. This had some advantages - the city was better protected from enemies and from floods.

Over time, the city was completely destroyed, and only a hill (“tell” in Arabic) remained. Careful archaeological excavations on these hills revealed habitable layers one after another, and the deeper the archaeologists dug, the more primitive the traces of life became. This is clearly visible in Yarmo, for example.

The hill of Tell Hassun, on the upper Tigris, about 100 km west of Yarmo, was excavated in 1943. Its oldest layers contain painted pottery more advanced than any findings from ancient Yarmo. It is believed to represent the Hassun-Samarran period of Mesopotamian history, which lasted from 5000 to 4500 BC. e.

The hill of Tell Halaf, about 200 km upstream, reveals the remains of a town with cobblestone streets and more advanced brick houses. During the Khalaf period, from 4500 to 4000 BC. e., ancient Mesopotamian ceramics reaches its highest development.

As Mesopotamian culture developed, techniques for using river water improved. If you leave the river in its natural state, you can only use fields located directly on the banks. This sharply limited the area of usable land. Moreover, the volume of snowfall in the northern mountains, as well as the rate of snowmelt, vary from year to year. There were always floods at the beginning of summer, and if they were stronger than usual, there was too much water, while in other years there was too little.

People figured out that a whole network of trenches or ditches could be dug on both banks of the river. They diverted water from the river and brought it to each field through a fine network. Canals could be dug along the river for kilometers, so that fields far from the river still ended up on the banks. Moreover, the banks of canals and rivers themselves could be raised with the help of dams, which water could not overcome during floods, except in places where it was desirable.

In this way it was possible to count on the fact that, generally speaking, there would be neither too much nor too little water. Of course, if the water level fell unusually low, the canals, except those located near the river itself, were useless. And if the floods were too powerful, the water would flood the dams or destroy them. But such years were rare.

The most regular water supply was in the lower reaches of the Euphrates, where seasonal and annual fluctuations in level are less than on the turbulent Tigris River. Around 5000 BC e. in the upper reaches of the Euphrates, a complex irrigation system began to be built, it spread down and by 4000 BC. e. reached the most favorable lower Euphrates.

It was on the lower reaches of the Euphrates that civilization flourished. Cities became much larger, and in some by 4000 BC. e. the population reached 10 thousand people.

Such cities became too large for the old tribal systems, where everyone lived as one family, obeying its patriarchal head. Instead, people without clear family ties had to settle together and cooperate peacefully in their work. The alternative would be starvation. To maintain peace and enforce cooperation, a leader had to be elected.

Each city then became a political community, controlling the agricultural land in its vicinity in order to feed the population. City-states arose, and each city-state was headed by a king.

The inhabitants of the Mesopotamian city-states essentially did not know where the much-needed river water came from; why floods occur in one season and not another; why in some years they do not exist, while in others they reach disastrous heights. It seemed reasonable to explain all this as the work of beings much more powerful than ordinary people - the gods.

Since it was believed that fluctuations in water levels did not follow any system, but were completely arbitrary, it was easy to assume that the gods were hot-tempered and capricious, like extremely strong overgrown children. In order for them to give as much water as needed, they had to be cajoled, persuaded when they were angry, and kept in a good mood when they were peaceful. Rituals were invented in which the gods were endlessly praised and tried to appease.

It was assumed that the gods liked the same things that people liked, so the most important method of appeasing the gods was to feed them. It is true that the gods do not eat like men, but the smoke from the burning food rose to the sky, where the gods were imagined to live, and animals were sacrificed to them by burning*.

An ancient Mesopotamian poem describes a great flood sent by the gods that destroys humanity. But the gods, deprived of sacrifices, became hungry. When a righteous survivor of the flood sacrifices animals, the gods gather around impatiently:

The gods smelled it

The gods smelled a delicious smell,

The gods, like flies, gathered over the victim.

Naturally, the rules of communication with the gods were even more complex and confusing than the rules of communication between people. A mistake in communicating with a person could lead to murder or bloody feud, but a mistake in communicating with God could mean famine or a flood that devastates the entire area.

Therefore, in agricultural communities a powerful priesthood grew up, much more developed than that which can be found in hunting or nomadic societies. The kings of the Mesopotamian cities were also high priests and offered sacrifices.

* The idea that the gods lived in the sky may have stemmed from the fact that the earliest farmers depended on rain falling from the sky rather than on river floods. (Note by author)

The center around which the entire city revolved was the temple. The priests who occupied the temple were responsible not only for the relationship between people and gods, but also for the management of the city itself. They were treasurers, tax collectors, organizers - the bureaucracy, the bureaucracy, the brain and heart of the city.

Source -

How to enter the school portal of the Moscow region on the electronic diary Electronic school diary

How to enter the school portal of the Moscow region on the electronic diary Electronic school diary Sumerian civilization Sumerian village river canals vegetation 2 huts

Sumerian civilization Sumerian village river canals vegetation 2 huts Knowledge lesson in first grade

Knowledge lesson in first grade