The bloc's ambivalent attitude towards the revolution. The bloc's attitude to the revolution

A.A. Blok expresses his thoughts about the revolution and the fate of man in an era of colossal achievements in the article “Intellectuals and the Revolution”, in the poems “Scythians” and “The Twelve”. Let's consider one of these poems, which, in the author's opinion, best reflects the era of revolutions and their contradictions.

The poem "12" is a reflection of that era and those events that shook the entire country with the change of the state apparatus. The revolution was spontaneous, the poem was also written in a fit of impulse, and therefore in the work itself, “one dusty blizzard,” the poet compares the revolution with an unexpected snowstorm that swept away everything in its path.

The poetic rhythm and solemn vocabulary of the poem give it a marching sound. A.A. Blok in one of his sayings calls the revolution music and calls on people to “listen to it with their whole body, with their whole heart and with their whole mind.” This helps to fully experience the mood that reigned in the country at that time.

Immediately after its appearance, the poem “The Twelve” caused the most fierce debate and contradictory interpretations. Some rejected it with contempt as “Bolshevik,” others saw in it and its heroes the evil truth of the Bolsheviks. And there are reasons for this.

On the one hand, this is the confident march of twelve Red Guards walking along the streets of snow-covered Petrograd, and the church already infringed on its rights (“And there’s the long-skirted one - / With his side behind the snowdrift... / Why is he so sad now, / Comrade priest?”), which shows the power of the Bolsheviks.

On the other hand, Blok characterizes his heroes as follows:

And they go without the name of a saint

All twelve - into the distance.

Ready for anything

No regrets...

And also: “There’s a cigar in your teeth, they’ll take a cap, / You should have an ace of diamonds on your back!” The poet openly compares revolutionaries with convicts and shows that these people are ready for anything, that in their souls there is only “sad, black” albeit “holy malice.” And after we see that Petka’s comrades mock him, calling him a weakling, after Petya’s murder, and declare impending robberies and beatings, it becomes clear that these are people who do not have any spiritual culture and the foundations of morality and honor, that under the sick idea of a bright future hide insignificant and vile people.

The symbolism of the main elements of the poem is even more confusing. For example, the number twelve is found in many religions and mythologies: the 12 apostles in Christianity, the 12 most important Christian holidays in Orthodoxy, Hercules performed 12 labors, in Buddhism the process of rebirth of living beings was a “wheel” formed by 12 steps, and so on, in addition to this, There are 12 months in a year, and watches are traditionally made with a 12-hour dial. In Blok, this number appears three times: the name, the number of Red Guards and the number of chapters, and as we know, 3 is also a symbolic number. Of particular significance is the appearance of Jesus Christ at the head of this detachment. It is no coincidence that the spelling of his name is the popular “Isus”, and not the book “Iesus”, which proves the national character of the work. And the fact that the bloody procession is led by the son of God depicts Blok’s pity for the main participants in the events of the era. Perhaps the poet believed that these people, who had forgotten about the Light within themselves for many reasons - centuries-old miserable life, grievances that had accumulated for a long time, lack of education, lack of internal culture, were worthy not of hatred, but of pity. Because they themselves don’t know what they are doing. That is why God is ahead of them - above his lost, blind children.

Thus, we see how Blok was inspired by the revolution and at the same time frightened by its mercilessness and cruelty. Not all the arguments of both sides are described above; the poem is filled with symbols, such as a dog with its tail between its legs and a complaining old woman, which make it special. Regarding the plan, the poet himself wrote: “... those who see political poems in “The Twelve” are either very blind to art, or sit up to their ears in political mud, or are possessed by great malice - be they enemies or friends of my poem " This poem is not propaganda, it is a picture of revolutionary reality with all its horrors and hopes, it, as a true creation of art, reflects the real thoughts and feelings of the people of its time.

Updated: 2018-05-20

Attention!

Thank you for your attention.

If you notice an error or typo, highlight the text and click Ctrl+Enter.

By doing so, you will provide invaluable benefit to the project and other readers.

Scary, sweet, inevitable, necessary

I should throw myself into the foamy shaft...

Blok expresses his thoughts about the revolution and the fate of man in an era of colossal achievements in the article “Intellectuals and the Revolution”, in the poems “Scythians” and “The Twelve”.

Let us make an attempt to understand Blok’s worldview through his crowning work, “The Twelve.” The poem was written in January 1918. The author's first entry about her was made on January 8. January 29 Blok writes: “Today I am a genius.” This is the only self-characterization of this kind in the entire creative destiny of the poet.

The poem becomes widely known. On March 3, 1918, it was published in the newspaper “Znamya Truda”, in April - together with an article about it by the critic Ivanov-Razumnik, “Test in a thunderstorm and storm” - in the magazine “Our Way”. In November 1918, the poem “The Twelve” was published as a separate brochure.

Blok himself never read “The Twelve” aloud. However, in 1918–1920. At Petrograd literary evenings, the poem was read more than once by L. D. Blok, the poet’s wife and professional actress.

The appearance of the poem caused a storm of contradictory interpretations. Many of Blok’s contemporaries, even former close friends and associates, decisively and completely did not accept it. Among the irreconcilable opponents of the “Twelve” were Z. Gippius, N. Gumilyov, I. Bunin. Ivanov-Razumnik, V. Meyerhold, and S. Yesenin accepted the poem with delight. Blok received an approving review from A. Lunacharsky.

The most complex, subtle, and meaningful was the reaction of those who, without accepting the “topical meaning” of “The Twelve,” saw the brilliance, depth, tragedy, poetic novelty, and high inconsistency of the poem. This is how M. Voloshin, N. Berdyaev, G. Adamovich, O. Mandelstam and others rated “The Twelve”.

Listen to how M. Voloshin expressed his impressions:

The poem “The Twelve” is one of the beautiful artistic translations of revolutionary reality. Without betraying himself, Blok wrote a deeply real and - surprisingly - lyrically objective thing. The internal affinity of “The Twelve” with “Snow Mask” is especially striking. This is the same St. Petersburg winter night, the same St. Petersburg blizzard... the same wine and love frenzy, the same blind human heart that has lost its way among the snow whirlwinds, the same elusive image of the Crucified, sliding in the snow flames... To the transmission of carbon monoxide and Blok approached the dull lyrics of his heroes through the tunes and rhythms of ditties, street and political songs, common words and popular democratic words. The poet's musical task was to create a subtly noble symphony of rhythms from deliberately vulgar sounds.

...There is nothing unexpected in this appearance of Christ at the end of the blizzard Petersburg poem. As always with Blok, He is invisibly present and shines through the obsessions of the world, just as the Beautiful Lady shines through the features of Harlots and Strangers. After the first - “Eh, eh without a cross” - Christ is already here...

Now it (the poem) is used as a Bolshevik work, with the same success it can be used as a pamphlet against Bolshevism, distorting and emphasizing its other aspects. But its artistic value, fortunately, stands on the other side of these temporary fluctuations in the political exchange.

Blok felt the direction of the historical movement and brilliantly conveyed this future unfolding before his eyes: the state of souls, the mood, the rhythms of the procession of some segments of the population and the ossified doom of others.

Blok's attitude towards the poem was quite complex. In April 1920, a “Note about the Twelve” was written: “... In January 1918, for the last time, I surrendered to the elements no less blindly than in January 1907 or March 1914... Those who see in the “Twelve” political poems, or are very blind to art, or sit up to their ears in political mud, or are possessed by great malice - be they enemies or friends of my poem.” (Here Blok compares this poem with the cycles “Snow Mask” and “Carmen”.)

The poem “The Twelve” was the result of Blok’s knowledge of Russia, its rebellious elements, and creative potential. Not in defense, not in glorification of the “coup party” - but in defense of the “people's soul”, slandered and humiliated (from Blok’s point of view), erupting in rebellion, maximalist “all or nothing”, standing on the brink of death, cruel punishment - it was written poem. Blok sees and knows what is happening: the shelling of the Kremlin, pogroms, the horror of lynchings, burning of estates (Blok’s family estate in Shakhmatovo was burned), the dispersal of the Constituent Assembly, the murder of the ministers of the Provisional Government Shingarev and Kokoshkin in the hospital. According to A. Remizov, the news of this murder became the impetus for the start of work on the poem. In these “lifeless” weeks of January 1918, Blok considered it the highest duty of a Russian artist, a “repentant nobleman,” a lover of the people to give to the people, to sacrifice to the will of the “people’s soul,” even his last asset—the measure and system of ethical values.

The poem is dictated by this sacrifice, awareness of one’s strength, immeasurable, unreasoning pity. Voloshin will call her “a merciful representative for the soul of Russian Razinovism.”

- A. Blok's attitude to the revolution.

- Revolution as a “world fire”.

- Spontaneous beginning in the revolution.

- Revolution and the devaluation of moral standards.

- The popular character of the revolution.

In the article “Intellectuals and Revolution” A. Blok wrote: “Revolution, like a thunderstorm, like a snowstorm, always brings something new and unexpected; she cruelly deceives many; she easily cripples the worthy in her whirlpool; she often brings the unworthy to land unharmed; but this does not change either the general direction of the flow or that menacing and deafening noise. This hum is still about great things...”

These words very accurately express Blok’s attitude to what was happening in 1917. According to the testimony of many, Blok greeted the revolution with enthusiasm and rapture. A person close to the poet wrote: “He walked young, cheerful, cheerful, with shining eyes.” Among the very few representatives of the artistic and scientific intelligentsia at that time, the poet immediately declared his readiness to cooperate with the Bolsheviks, with the young Soviet government. Responding to a questionnaire from one of the bourgeois newspapers “Can the intelligentsia work with the Bolsheviks?”, he, the only one of the participants in the questionnaire, answered: “It can and must.” When literally a few days after the October coup, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, newly created at the Second Congress of Soviets, invited Petrograd writers, artists, and theater workers to Smolny, only a few people responded to the call, and among them was Alexander Blok.

First of all, Blok understood and accepted the October Revolution as a spontaneous, uncontrollable “world fire”, in the purifying fire of which the entire old world should be incinerated without a trace. He's writing:

We, to the grief of all the bourgeoisie, will fan the world fire, the world fire in the blood - God bless!

It was in this destruction of the old, outdated and rotten world that Blok saw the most important goal and task of the revolution. Hence the image of the revolution that the poet creates in the poem “The Twelve” - a work entirely dedicated to that era.

Due to the fact that the main thing for Blok in the revolution was its destructive beginning, the image of the revolution in the poem contains a lot of spontaneous, natural things. Therefore, images of blizzards and wind acquire special significance. They are the ones who symbolize the natural principle in the revolution. Like the revolution itself, the blizzard in the poem is beyond the control of human will. She acts only according to her whim, and people can only obey.

So, for example, the wind in the poem whips the enemies of the revolution: a lady in karakul, a priest, a writer, but at the same time

Tears, crumples and mows

Large poster:

“All power to the Constituent Assembly!”

Alexander Blok very accurately sensed the terrible thing that entered people’s lives with the revolution: the complete devaluation of human life, which is no longer protected by any law (no one even thinks that they will have to answer for Katka’s murder). Moral feeling does not keep one from killing either - moral concepts have become extremely devalued. It is not without reason that after the death of the heroine, revelry begins, now everything is permitted:

Lock the floors, Now there will be robberies! Unlock the cellars There's a bastard walking around these days!

Even faith in God is unable to keep from dark, terrible manifestations of the irrepressibility of the human soul. She, too, is lost, and the Twelve, who went “to serve in the Red Guard,” understand this themselves:

Petka! Hey, don't lie! What did the Golden Iconostasis save you from?"

and add:

Are your hands not bleeding because of Katya’s love? "

From the above lines from the poem it is clear that Blok’s perception of the revolution was exclusively of a popular nature, as almost all researchers rightly pointed out. The revolution, according to Blok, splashed onto the forefront of history the masses - the bearers of elemental forces, which become the driving force of the world historical process. “Revolution is: I am not alone, but we. The reaction is loneliness, mediocrity...,” Blok wrote in his diary. The poem “The Twelve,” already completed by that time, convincingly shows that the poet saw in the people not a faceless element, but many individual personalities.

Not being a revolutionary, a comrade-in-arms of the Bolsheviks, a “proletarian” writer or “coming from the lower classes”, Blok accepted the revolution, but accepted October as a fatal inevitability, as an inevitable event in history, as a conscious choice of the Russian intelligentsia, thereby bringing the great national tragedy closer. Hence his perception of the revolution as retribution to the old world. The revolution is retribution against the former ruling class, the intelligentsia cut off from the people, the refined, “pure”, largely elitist culture, of which he himself was the leader and creator.

The twentieth century was a difficult and dramatic period in the history of our state. At this time, the birth of a new state took place. This is a time of difficult trials and changes. The revolutionary events of 1917-1918 left their mark on the history of Russia. The revolution shook a huge country, it did not go unnoticed and affected everyone. Alexander Blok also did not remain indifferent. He expressed his attitude to revolutionary events in the poem “The Twelve.”

In parallel with the poem "" Blok worked on the poem "Scythians" and the article "Intellectuals and Revolution." These creative works also reflect the author’s attitude to the events of 1917-1918.

It is worth noting that Blok perceived the beginning of the revolution joyfully and enthusiastically. He called to listen to the voice of the revolution and follow it. The author saw something new and different in the revolution. Blok believed that now life in Russia would change. But later, we see how this delight goes away, the attitude towards the events changing. Blok tries to objectively look at revolutionary events and evaluate them. The poem “The Twelve” became a reflection of the author’s objective thoughts about those events.

The revolution in the poem “The Twelve” is shown as a spontaneous and uncontrolled event. The author compares it to a blizzard and blizzard, to a blizzard that sweeps away everything in its path. For Blok, the revolution became an inevitable event. It contains all the discontent and hatred that in an instant broke free and is now sweeping across the expanses of a great country, sweeping away figures of “bourgeois vulgarity.”

The revolution breaks the old world of “ladies”, “bourgeois”, “vitiy”. She is merciless to them. In the lines of the poem we hear lines about the death of Russia. But that's not true. The old world is dying, and a new one is taking its place.

For Blok, the revolution has two sides: black and white. Everything that happened at that time was drenched in blood and violence, accompanied by robberies and murders. That is why throughout the entire work there is a struggle between “black evening” and “white snow”. Blok is trying to understand whether a revolution can really create something new or is it only capable of destruction.

The driving force of the revolution is the image of the twelve. These are ordinary soldiers who walk with confident steps along the streets of a revolutionary city. The block does not clearly refer to them. In the poem, they are first depicted as bandits (“cigarettes in their teeth, wearing a cap”), but then the author says that they are simple Russian guys who went to serve in the Red Army. Then again Block shows their dirty deeds. They pour out their anger and hatred on innocent people. The Twelve kill Katka without any doubt, just because she is now with someone else.

The image of the revolution in the poem “The Twelve” is inextricably linked with the image of Christ. Although the twelve are constantly trying to get rid of him, he still leads their “victorious” procession. Christ, as once upon a time, once again descended to earth to illuminate the right path for the lost.

In the poem “The Twelve,” Blok never assesses the events taking place. The revolution for the author became an inevitable event, but he was never able to understand its cruelty and inhumanity.

Essay text:

Blok expressed his attitude towards the revolution and everything that followed it in the poem Twelve, written in 1918. It was a terrible time: the Bolsheviks came to power, four years of war, devastation, murders were behind us. People who belonged to the large intelligentsia, which included Blok, perceived what was happening as a national tragedy. And against this background, Blok’s poem sounded in clear contrast, in which the poet, who quite recently wrote heartfelt lyrical poems about Russia, directly says: Let’s fire a bullet at Holy Rus'.

Contemporaries did not understand Blok and considered him a traitor to his country. However, the poet’s position is not as clear-cut as it might seem at first glance, and a more careful reading of the poem proves this.

Blok himself warned that one should not overestimate the importance of political motives in the poem Twelve; the poem is more symbolic than it seems. In the center of Blok’s poem we put a blizzard, which is the personification of the revolution. In the midst of this blizzard, snow and wind, you can hear the music of the revolution, which for him is opposed to the most terrible philistine peace and comfort. In this music he sees the possibility of the revival of Russia, the transition to a new stage of development. The bloc does not deny or approve of the riots, robberies, seething dark passions, permissiveness and anarchy that have reigned in Russia. In all this terrible and cruel present, Blok sees the cleansing of Russia. Russia must pass this time, plunging to the very bottom, into hell, into the underworld, and only after that will it ascend to heaven.

The fact that Blok sees in the revolution a transition from darkness to light is proven by the very title of the poem. Twelve is the hour of transition from one day to another, an hour that has long been considered the most mystical and mysterious of all. What was happening at that moment in Russia, too, according to Blok, emanated a certain mysticism, as if someone unknown and omnipotent at the midnight hour began to practice witchcraft.

The most mysterious image of the poem, the image of Christ walking ahead of a detachment of Red Army soldiers, is also associated with this motif. Literary scholars offer many interpretations of this image. But it seems to me that Blok’s Jesus Christ personifies the future of Russia, bright and spiritual. This is indicated by the order in which the characters appear at the end of the poem. Behind everyone trudges a mangy dog, in whose image one can easily guess the autocratic and dark past of Russia, ahead of him walks a detachment of Red Army soldiers, personifying the revolutionary present of the country, and this procession is led in a white corolla of roses by Jesus Christ, an image embodying the bright future awaiting Russia when she will rise from the hell she finds herself in.

There are other interpretations of this image. Some literary scholars believe that Jesus Christ (this version appeared due to the fact that Blok is missing one letter in the name of Jesus, and this cannot be called an accident or the necessity of the verse) is the Antichrist, leading a detachment of Red Army soldiers, and therefore the entire revolution. This interpretation is also consistent with Blok’s position regarding the revolution as a transitional period to the kingdom of God.

The poem Twelve still causes a lot of controversy among critics and readers. The plot of the poem and its images are explained in different ways. However, one thing leaves no doubt. At the time of its writing, Blok treated the revolution as a necessary evil that would help lead Russia to the true path and revive it. Then his views will change, but at that moment Blok believed in the revolution, like a sick person believes in an operation that, although it causes pain, will nevertheless save him from death.

The rights to the essay “Attitude to the Revolution of the Author of the Twelve Poem” belong to its author. When quoting material, it is necessary to indicate a hyperlink to

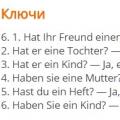

Usage and conjugation of the verbs sein and haben

Usage and conjugation of the verbs sein and haben Linguistic means characteristic of reasoning

Linguistic means characteristic of reasoning Personality and self-education Examples of personal self-development in literature

Personality and self-education Examples of personal self-development in literature