HABEN or SEIN, haben oder sein. Usage and conjugation of the verbs sein and haben

In German, the present tense (Präsens) is conjugated incorrectly. Please note that when conjugating a verb haben in the 2nd and 3rd person singular root vowel b falls out.

Verb conjugations haben in Präsens you need to learn.

*In verb haben The sound [a] in the 2nd and 3rd person singular is read briefly, in all other persons it is read long.

Remember that after the verb haben nouns are used in Akkusativ, as a rule, with an indefinite article. The construction Ich habe, du hast... is translated I have it, you have it, For example:

Sie hat einen Bruder und eine Schwester. She has a brother and a sister.

In sentences with a verb haben in meaning have verb haben unstressed. The direct object is under the main stress, and the subject is under the secondary stress if it is expressed by a noun.

Exercises

1. a) conjugate the following sentences with the verb haben in Präsens.

Ich habe eine ‘Tochter und einen ‘Sohn.

b) Read the following sentences with the verb haben out loud, translate the sentences into Russian.

1. Hat er diese Karte? - Ja, er hat diese Karte.

2. Hast du einen Text? - Ja, ich habe einen Text.

3. Haben sie (they) ein Kind? - Ja, sie haben eine Tochter.

4. Habt ihr eine Wohnung? - Ja, wir haben eine Wohnung.

2. Sentences must be supplemented with nouns that are given below the line; they must be placed in Akkusativ.

1. Meine Schwester hat….

2. Wir haben….

3. Mein Bruder hat… .

4. Sie hat….

5. Diese Aspiranten haben… .

___________________________________________

eine Tante, ein Sohn, ein Sohn, dieses Buch, diese Wohnung

3. Read the following sentences, answer the questions in the affirmative, use the verb haben in your answers. Don't forget to put the noun in Akkusativ.

For example: Sie haben eine Schwester. Und Sie?

Ich habe auch eine Schwester.

1. Meine Schwester hat eine Tochter. Und Sie?

2. Mein Vater hat ein Auto. Und du?

3. Mein Kollege hat ein Zimmer. Und Sie?

4. Diese Frau hat eine Tante. Und du?

4. Give affirmative answers to the questions; you need to change the possessive pronoun accordingly.

For example: - Hat deine Schwester einen Sohn?

- Ja, meine Schwester hat einen Sohn.

1. Hat Ihre Tante ein Kind?

2. Hat Ihr Kollege eine Tochter?

3. Hat Ihre Mutter einen Bruder?

4. Hat Ihr Kollege eine Tante?

5. Hat Ihr Sohn einen Freund?

5. How would you phrase your question to get the following answer? You need to remember what the word order is in a question sentence without a question word.

Sample: - Ja, ich habe ein Buch. - Hast du ein Buch?

1. Ja, sie (they) haben ein Heft.

2. Ja, sie hat ein Rind.

3. Ja, meine Schwester hat eine Tochter.

4. Ja, mein Freund hat eine Karte.

5. Ja, das Mädchen hat einen Bruder und eine Schwester.

6. Translate the sentences into German.

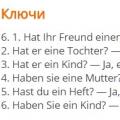

1. Does your friend have a son? - Yes, he has a son.

2. Does he have a daughter? - Yes, he has a daughter.

3. Does he have a child? - Yes, he has a child.

4. Do they have a mother? – Yes, they have a father and a mother.

5. Do you have a notebook? - Yes, I have a book and notebook.

6. Do you have a child? - Yes, we have a child.

More about verb conjugation in Präsens and

Past tense (Präteritum)

Except Perfect (perfect tense) There is also a simple past tense in the German language - Präteritum(which in Latin means past past). It is formed using the suffix -t-. Compare:

Ich tanze. – I am dancing (present tense – Präsens).

Ich tanz t e. – I danced (past tense – Präteritum).

This is similar to the English past tense, where the sign of the past tense is the suffix -d-:

I dance – I danced.

Präsens Präteritum

ich sage - I say ich sagte - I said

wir, sie, Sie sagen wir, sie, Sie sagten

du sagst du sagtest

er sagt er sagte (!)

ihr sagt ihr sagtet

Feature Präteritum is what is in the form he she it) no personal ending added -t, that is: forms I And He match up. (As you remember, the same thing happens with modal verbs.)

As we have already said, the German language has strong (irregular, non-rule) verbs. Sagen – weak, regular verb. And here fallen – strong:

ich, er fiel (I, he fell), wir, sie, Sie fielen,

du fielst,

ihr fielt.

The past tense suffix is no longer needed here -t-, since the past tense is indicated by the changed word itself (compare with English: I see - I see, I saw - I saw). Forms I And He are the same, there are no personal endings in these forms (all the same as with modal verbs in the present tense).

So, the Russian phrase I bought beer It can be translated into German in two ways:

Ich kaufte Bier. – Präteritum (past tense).

Ich habe Bier gekauft. – Perfect (perfect tense).

What is the difference?

Perfect is used when an action performed in the past is connected with the present moment, when it is relevant. For example, you come home and your wife asks you (as they say, dreaming is not harmful):

Hast du Bier gekauft? – Did you buy beer?

Ja, ich habe Bier gekauft.(You answer with a sense of accomplishment).

She is not interested in the moment in the past when you bought beer, not in history, but in the result of the action - that is, the availability of beer. Is it done or not? Has it happened or not? Hence the name - Perfect (perfect tense).

Präteritum (past tense) used when an action performed in the past has nothing to do with the present moment. It's just a story, a story about some past events. That's why Perfect is used, as a rule, in conversation, in dialogue, when exchanging remarks (after all, it is in conversation that what is most often important is not the action itself in the past, but its relevance for the present, its result), and Präteritum- in a story, in a monologue. For example, you talk about how you spent your vacation:

Ich kaufte ein paar Flaschen Bier... Dann ging ich an den Strand... – I bought a few bottles of beer, went to the beach...

Or tell your child a fairy tale:

Es war einmal ein König, der hatte drei Töchter... - Once upon a time there was a king, he had three daughters...

Ich kam, ich sah, ich siegte. – I came, I saw, I conquered.

Because the Präteritum needed, as a rule, for a story, then the second person form ( you you) are rarely used. Even in a question to a person telling about something, it is more often used Perfect – so used to it that this form is for replicas, Präteritum with this interruption of the narrator it sounds very literary (albeit beautiful): Kauftest du Bier? Gingt ihr dann an den Strand? Basically, you will encounter and use the following two forms:

(ich, er) kaufte, wir (sie) kauften– for weak verbs,

(ich, er) ging, wir (sie) gingen– for strong verbs.

Table - formation of the preterite:

So: in conversation you use Perfect, in a story (about events not related to the present moment) - Präteritum.

However Präteritum verbs sein, haben and modal verbs (+ verb wissen) is also used in conversation - along with Perfect:

Ich war in der Türkei. (Präteritum) – I was in Turkey.

= Ich bin in der Türkei gewesen. (Perfect)

Ich hatte einen Hund. (Präteritum) – I had a dog.

= Ich habe einen Hund gehabt. (Perfect)

Ich musste ihr helfen. (Präteritum) – I had to help her.

= Ich habe ihr helfen müssen. (Perfect)

Ich wusste das. (Präteritum) - I knew it.

Ich habe das gewusst. (Perfect)

Past tense forms sein -> war (du warst, er war, wir waren…) And haben -> hatte (du hattest, er hatte, wir hatten…) need to remember.

Modal verbs form Präteritum as weak - by inserting a suffix -t-, with the only peculiarity that Umlaut (mutation) in this case it “evaporates”: müssen -> musste, sollen -> sollte, dürfen -> durfte, können -> konnte, wollen -> wollte.

For example:

Ich konnte in die Schweiz fahren. Ich hatte Glück. Ich war noch nie in der Schweiz. – I was able to go to Switzerland. I was lucky (I was lucky). I've never been to Switzerland before.

Separately, you need to remember: mögen -> mochte:

Ich mochte früher Käse. Jetzt mag ich keinen Käse. – I used to love cheese. Now I don't like cheese.

Now we can write down the so-called basic forms of the verb (Grundformen):

Infinitiv Präteritum Partizip 2

kaufen kaufte gekauft

(buy) (bought) (purchased)

trinken trunk getrunken

For weak verbs, there is no need to memorize the basic forms, since they are formed regularly. The basic forms of strong verbs must be memorized (as, by the way, in English: drink – drank – drunk, see – saw – seen…)

For some strong verbs, as you remember, you need to remember the present tense form (Präsens) – for forms You And he she it): nehmen – er nimmt (he takes), fallen – er fällt (he falls).

Of particular note is a small group of verbs intermediate between weak and strong:

denken – dachte – gedacht (to think),

bringen – brachte – gebracht (bring),

kennen – kannte – gekannt (to know, to be familiar),

nennen – nannte – genannt (to name),

rennen – rannte – gerannt (run, rush),

senden – sandte – gesandt (to send),

(sich) wenden – wandte – gewandt (to address).

They get in Präteritum and in Partizip 2 suffix -t, like weak verbs, but at the same time they change the root, like many strong ones.

For senden And wenden weak forms are also possible (although strong (with -A-) are used more often:

Wir sandten/sendeten Ihnen vor vier Wochen unsere Angebotsliste. – We sent you a list of proposals four weeks ago.

Sie wandte/wendete kein Auge von ihm. – She didn’t take her eyes off him (didn’t turn away).

Haben Sie sich an die zuständige Stelle gewandt/gewendet? – Have you contacted the appropriate (responsible) authority?

If senden has the meaning broadcast, A wenden – change direction, turn over, then only weak forms are possible:

Wir sendeten Nachrichten. - We conveyed the news.

Er wendete den Wagen (wendete das Schnitzel). – He turned the car (turned the schnitzel over).

Jetzt hat sich das Blatt gewendet. – Now the page has turned (i.e. new times have come).

There are several cases where the same verb can be both weak and strong. At the same time, its meaning changes. For example, hängen in meaning hang has weak forms, and in the meaning hang - strong (and in general, in such “double” verbs, the active “double”, as a rule, has weak forms, and the passive one has strong forms):

Sie hängte das neue Bild an die Wand. – She hung a new picture on the wall.

Das Bild hing schief an der Wand. – The picture hung crookedly on the wall.

Hast du die Wäsche aufgehängt? -Have you hung up your laundry?

Der Anzug hat lange im Schrank gehangen. – This suit hung in the closet for a long time.

Verb erschrecken – weak if it means frighten, and strong if it means get scared:

Er erschreckte sie mit einer Spielzeugpistole. “He scared her with a toy gun.”

Sein Aussehen hat mich erschreckt. – His (appearance) frightened me.

Erschrecke nicht! - Do not scare!

Sie erschrak bei seinem Anblick. – She was scared when she saw him (literally: when she saw him).

Ich bin über sein Aussehen erschrocken. – I’m scared by his appearance (the way he looks).

Erschrick nicht! - Do not be afraid!

Verb bewegen could mean like move, set in motion(and then he is weak), so encourage(strong):

Sie bewegte sich im Schlaf. – She moved (i.e., tossed and turned) in her sleep.

Die Geschichte hat mich sehr bewegt. – This story really touched me.

Sie bewog ihn zum Nachgeben. – She prompted, forced him to yield (prompted him to yield).

Die Ereignisse der letzten Wochen haben ihn bewogen, die Stadt zu verlassen. “The events of recent weeks have prompted him to leave the city.

Verb schaffen - weak in meaning to work hard, to cope with something(by the way, the motto of the Swabians, and indeed the Germans in general: schaffen, sparen, Häusle bauen - to work, save, build a house) and strong in meaning create, create:

Er schaffte die Abschlussprüfung spielend. – He passed the final exam effortlessly.

Wir haben das geschafft! – We achieved it, we did it!

Am Anfang schuf Gott Himmel und Erde. – In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.

Die Maßnahmen haben kaum neue Arbeitsplätze geschaffen. – These events did not create new jobs.

Conjugation of the verbs haben and sein in the present

Let me remind you that present (Präsens) is the present tense of the verb. Verbs haben"have" and sein“to be, to appear” are the most frequent in the German language, since their functions are very diverse. Beginners learning German, as a rule, take them up at the very first steps, because it is impossible to do without it. It is important to know that these verbs are irregular, since the formation of their forms in the present tense (and not only in the present) differs from the generally accepted one. But there is no harm in this: frequency verbs quickly enter the vocabulary of beginners, since they will have to work with them very often. And in the future, conjugating irregular verbs will become automatic. Actually, let's move on to verbs.

In Russian we say: “I am an actor”, “you are a teacher”, “he is a student”. The Germans literally say: “I am an actor,” “you are a teacher,” “he is a student.” In this case we use the verb sein, which has various shapes. If we want to say “I have (something or someone)”, we use the verb haben. Literally, the Germans say “I have (something or someone).” To say all this in German depending on person, number and gender, refer to the table below.

The table is quite easy to navigate. You associate the desired personal pronoun (§ 15) with the desired verb and then put the word you need (nouns take the required number). For example, verb sein with a noun:

You can, for example, say “I am good”, “he is bad”. In this case, after the verb there is a regular adjective without any changes.

With verb haben in the same way, just don’t forget about articles (§ 7), if they are needed. And one more thing... since you can have anything and in any quantity, nouns can be in any number.

There are some stable phrases like Zeit haben"to have time" Unterricht haben"to have classes" Angst haben“to be afraid”, which can be without an article.

- Ich muss los. Ich habe keine Zeit.- I have to go. I have no time.

- Heute habe ich Unterricht.- Today I have classes.

- Ich habe Angst vor diesem Hund.- I'm afraid of this dog.

Verbs sein And haben also participate in the formation of various tense constructions as auxiliary verbs. More on this in other paragraphs.

Step 5 – two of the most important and most commonly used words in the German language: the verbs haben and sein.

haben- have

sein- be

The conjugation of these two verbs is different from the others. Therefore, you just need to remember them.

haben

| ich | habe | wir | haben |

| du | hast | ihr | habt |

| er/sie/es | hat | Sie/sie | haben |

sein

| ich | bin | wir | sind |

| du | bist | ihr | seid |

| er/sie/es | ist | Sie/sie | sind |

It's interesting that verbs haben And sein are used in German much more often than in Russian. There is no verb in the sentence “I am Russian” - we simply don’t say it. In German, all sentences have a verb, so this sentence sounds like this: Ich bin Russe. (I am Russian).

Another example. In Russian we say “I have a car.” The Germans formulate this phrase differently - “Ich habe ein Auto” (I have a car). That is why these verbs are the most common in the German language.

Here are two fun videos to help you remember these verbs faster:

Verbs haben and sein: examples

The most popular phrases with sein:

Wie alt bist du? — How old are you?

Ich bin 20 Jahre alt. — I am 20 years old.Wer best du? — Who are you?

Ich bin Elena (=Ich heiße Elena). — I'm Elena.

Wer sind Sie? — Who you are?

Ich bin Frau Krause. — I'm Frau Krause.

Wo seid ihr? — Where are you?

Wir sind jetzt in Paris. — We are in Paris.

Was it das? — What is this?

Das ist eine Yogamatte. — This is a yoga mat.

Examples with haben:

Wieviel Glaser hast du? — How many glasses do you have?

Ich habe zwei Glaser. — I have two glasses.

Woher hast du das? — Where did you get this from?

Was it du? — What do you have?

Ich habe Brot, Käse und Wurst. — I have bread, cheese and sausage.

Hat er Milch zu Hause? — Does he have milk at home?

Ja, er hat. — Yes, I have.

Wie viel Teller har er? — How many plates does he have?

Er hat 10 Teller. — He has 10 plates.

The most common verbs in the German language include the verbs “haben - to dispose, to have at disposal” and “sein - to exist, to be, to be”. The peculiarity of these verbs is that when used in German speech they do not necessarily carry a semantic load. In addition to being used in their usual lexical meaning, they are used as auxiliary verbs, which serve in German to form tense forms of the verb and other constructions. In this case, they do not have their usual dictionary meaning, and the lexical meaning is conveyed by the semantic verb with which they form the corresponding grammatical construction.

Related topics:

Verbs HABENand SEIN belong to irregular, in other words, irregular verbs of the German language, therefore their formation must be remembered: it is not subject to any template rules for the formation of verb forms. They also form the three main forms inherent in the German verb in a very unique way:

1st form: infinitive (indefinite form) = Infinitiv

2nd form: imperfect / preterit (past simple) = Imperfekt / Präteritum

3rd form: participle II (participle II) = Partizip II

1 – haben / 2 – hatte / 3 – gehabt

1 – sein / 2 – war / 3 – gewesen

German verb conjugation HABEN, SEIN in Präsens (present), Indikativ (indicative)

|

Singular, 1st-3rd person |

Plural, 1st-3rd person |

||||

German verb conjugation HABEN, SEIN in Präteritum (simple past), Indikativ (indicative)

|

Singular, 1st-3rd person |

Plural, 1st-3rd person |

||||

The verb SEIN is also called a linking verb. It received this name because, since the verb in a German sentence plays a primary role in the construction of a syntactic structure and its presence in the sentence is mandatory, then in cases where there is no verb in the sentence according to the meaning, it takes its place and connects the sentence into a single whole. This is not natural for the Russian language, so this rule must be firmly understood. For example:

- Er ist bescheuert, findest du nicht? – He (is) crazy, don’t you think?

- Dein Protege ist Elektronikbastler, und wir brauchen einen qualifizierten Funkingenieur. – Your protégé (is) is a radio amateur, and we need a qualified radio engineer.

Thus, in German, sentences of this kind must necessarily contain the linking verb SEIN. It is not translated into Russian.

Now let's look at the use of two main verbs of the German language as auxiliaries in the formation of tense verb forms - past complex tenses Perfekt and Plusquamperfekt, and the principle of choosing an auxiliary verb applies equally to both the indicative (Indikativ) and the subjunctive mood (Konjunktiv). When used in this function, the choice of verb is essential HABENor SEIN to construct a certain grammatical structure, which is dictated by the semantic features of the semantic verb and some of its other characteristics.

- Perfekt Indikativ = personal form sein / haben (Präsens) + semantic verb (Partizip II)

- Plusquamperfekt Indikativ = personal form haben / sein (Imperfekt) + semantic verb (Partizip II)

Choosing a verb as an auxiliary: HABENor SEIN

|

Choice HABEN |

SEIN selection |

| 1. For intransitive verbs that do not denote any movement in space or time, movement or transition from one state to another | 1. For intransitive verbs that denote any movement in space, movement |

| 2. For verbs that denote a long-term, time-extended state | 2. For intransitive verbs that denote a transition from one state to another |

| 3. For transitive verbs, which, accordingly, require a direct object in the accusative case after themselves * | 3. The verb SEIN itself in its usual lexical meaning “to be, to be, to exist” |

| 4. For reflexive verbs that are used with the particle sich and denote focus (return) on the character (subject) | 4. For a number of verbs that always form tense forms with SEIN and which need to be remembered: “become - werden”, “succeed - gelingen”, “meet - begegnen”, “stay - bleiben”, “happen, occur - passieren, geschehen » |

| 5. For modal verbs: “must = be obliged to smth. do – sollen”, “must = be forced to sth. to do - müssen", "to want, to like, to love - möchten", "to desire, to want - wollen", "to have the right, permission to do something, to be able - dürfen", "to be able, to be able, to be able - können" | |

| 6. For impersonal verbs used in impersonal sentences and denoting various natural phenomena (precipitation, etc.). | |

| 7. The verb HABEN itself in its usual lexical meaning “to have, possess, own” |

* Here it is very important to always take into account the fact that the transitivity / intransitivity property of Russian and German verbs when translated within a given language pair does not coincide in all cases, so you should always check (if you are not sure) the control of the verb in the dictionary.

Consider the choice and use of verbs HABENor SEIN as auxiliary examples. All examples are given in the indicative mood.

HABEN

(1) Nach der Gesellschafterversammlung hat er sich ganz schnell von seinen Kollegen verabschiedet. — After the meeting of the founders, he very quickly said goodbye to his colleagues. (Here we have an intransitive verb, in its semantics, which has nothing to do with movement or movement, so the Perfekt form is formed using “haben”).

(2) Gestern hatte er über drei Stunden am Nachmittag Geschlafen, was ihn wieder gesund und munter machte. “Yesterday he slept for more than three hours in the afternoon, which made him healthy and vigorous again. (The continuous state verb is used in Plusquamperfekt with “haben”).

(3) Anlässlich unseres letzten Aufenthaltes in Holland haben wir endlich unsere Freunde in Amsterdam be sucht und ihre Kinder kennengelern. – During our last stay in Holland, we finally visited our friends in Amsterdam and met their children. (Both verbs are transitive and form the perfect form with "haben").

(4) Dein Sohn hatsich immer sämtlichen Forderungen der Erwachsenen und allen möglichen festgelegten Regeln widersetzt. - Your son always resisted and did not comply with all the demands of adults and all sorts of strictly established rules. (The choice of the verb “haben” to form the Perfect form is due to the reflexivity of the semantic verb).

(5) Ehrlich gesagt ist es immer mein Wunschbuch gewesen. Ich habe aber immer gewollt es zu lesen und nie gelesen. – To be honest, I always dreamed of this book. However, I always wanted to read it and never did. (The modal verb forms perfect with “haben”).

(6) Erinnerst du dich an den Tag im Juni 1978, an welchem es richtig geschneit hat? - Do you remember that day in June 1978 when it really snowed? (“Haben” is chosen as the auxiliary verb to form the Perfect form, since we are dealing with an impersonal verb here).

(7) Ich habe nie ein eigenes Zimmer gehabt. – I have never had my own room. (The semantic verb “haben” forms a Perfect with the auxiliary verb “haben”).

SEIN

(1) In diese gemütliche Dreizimmerwohnung sind wir vor drei Jahren eingezogen. “We moved into this cozy three-room apartment three years ago. (The verb of motion forms the Perfect form with "sein").

(2) Am Ende dieses sehr schönen und eblebnisvollen Tages ist das Kind sofort eingeschlafen. – At the end of this wonderful and very eventful day, the child immediately fell asleep. (The choice of the verb “sein” to form the Perfect form is determined by the semantics of the semantic verb, which conveys the transition from one state to another).

(3) Sie haben mich mit jemandem verwechselt. Vorgestern war ich hier nicht gewesen. (Plusquamperfekt of the verb “sein” requires it as an auxiliary verb).

(4) A) Das ist unbegreiflich, dass uns so was passiert ist. “It’s inconceivable that something like this could happen to us.” (One of those verbs that always forms Perfect and Plusquamperfekt with the verb “sein”).

b) Gestern ist es dir richtig gut gelungen, alle unangenehmen Fragen ausweichend zu beantworten. – Yesterday you really successfully managed to avoid direct answers to all the unpleasant questions. (This verb always requires "sein" as an auxiliary).

V) Seine Schwester hatte das unangenehme Gefühl, dass ihr jemand ständig gefolgtwar. – His sister had an unpleasant feeling that someone was constantly watching her = someone was constantly chasing her. (With this verb, “sein” is always used as an auxiliary).

G) Dieser Junge ist mutterseelenallein geblieben, als er noch ganz klein war. “This boy was left alone in this world when he was still very small. (With this verb, “sein” is always used as an auxiliary).

d) In der Schwimmhalle war sie zufällig ihrer alten Schulfreundin begegnet. — In the pool she accidentally met her old school friend. (With this verb, “sein” is always used as an auxiliary).

e) Was nothing geschehenist, ist nothing geschehen. -What didn’t happen didn’t happen. (With this verb, “sein” is always used as an auxiliary).

The German language has a number of verbs that have several different meanings depending on their use in a particular context. The meaning that a verb conveys in a particular situation may determine whether it has certain qualities (for example, transitivity / intransitivity), and, accordingly, various auxiliary verbs will be selected to form tense forms. For example:

- So ein schönes und modernes Auto bin ich noch nie gefahren. “I have never driven such a magnificent modern car before.” (In this case we have an intransitive verb of movement, since it is used in the meaning of “to go”; accordingly, “sein” is chosen for the Perfect form).

Usage and conjugation of the verbs sein and haben

Usage and conjugation of the verbs sein and haben Linguistic means characteristic of reasoning

Linguistic means characteristic of reasoning Personality and self-education Examples of personal self-development in literature

Personality and self-education Examples of personal self-development in literature