Secrets of old paintings - "Troika" by Vasily Perov

Who among us does not remember Perov's famous "Troika": three tired and frozen children are dragging a sleigh with a barrel full of water along a winter street. Behind the wagon pushes an adult man. An icy wind blows in the face of the children. The wagon is accompanied by a dog running on the right in front of the children...

"Troika" is one of the most famous and outstanding paintings by Vasily Perov, which tells about the difficulties of peasant life. It was written in 1866. Its full name is Troika. Apprentice craftsmen carry water.

“Pupils” used to be the name given to village children driven to large cities for “fishing”. Child labor was exploited to the fullest in factories, workshops, shops and stores. It is not difficult to imagine the fate of these children.

From the memoirs of a student boy:

“We were forced to carry boxes weighing three or four pounds from the basement to the third floor. We carried boxes on our backs with rope straps. Climbing the spiral staircase, we often fell and crashed. And then the owner ran up to the fallen man, grabbed him by the hair and banged his head on the cast-iron stairs. All of us, thirteen boys, lived in the same room with thick iron bars on the windows. They fell on the bunk. Apart from a mattress stuffed with straw, there was no bed.

After work, we took off our dresses and boots, put on dirty robes, which we girded with a rope, and put on props on our feet. But we were not allowed to rest. We had to chop wood, heat stoves, set up samovars, run to the bakery, to the butcher shop, to the tavern for tea and vodka, to carry snow from the pavement. On holidays we were also sent to sing in the church choir. In the morning and in the evening we went with a huge tub to the pool for water and each time brought ten tubs ... "

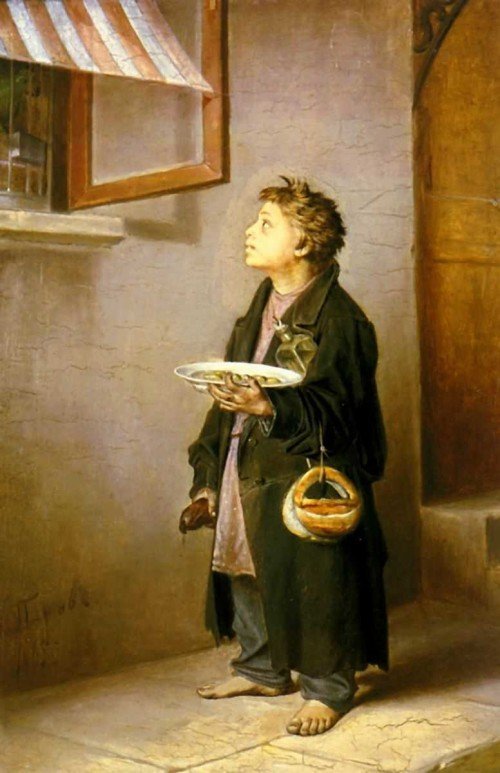

So lived the children depicted in Perov's painting. By the way, by the time Troika was written, many other paintings by the artist were also dedicated to children - for example, Orphans (1864), Seeing the Dead Man (1865), Boy at the Craftsman (1865).

Seeing the deceased, 1865. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow  "A artisan boy staring at a parrot", 1865. Ulyanovsk Art Museum

"A artisan boy staring at a parrot", 1865. Ulyanovsk Art Museum

The artist paid special attention to the problem of child labor even after writing Troika. All plots were taken from life and each subsequent picture aroused in the viewer a feeling of deep compassion and empathy. Nevertheless, it was Troika that became the “special canvas”. This is partly due to the story that accompanies the picture, filled with mental anguish, feelings and pain. This story will be shared one day by the author himself, in the short story "Aunt Marya". It must be admitted that Vasily Grigorievich was not only an outstanding artist, but also a talented, interesting storyteller. Thanks to this story, the painting got into the tops of the most discussed masterpieces of Russian art at the exhibition "Secrets of Old Paintings" in 2016, at the State Tretyakov Gallery.

The story tells us about the tragic fate of the boy - the main, central character of the picture. So, the story "Aunt Marya", author Vasily Perov:

“A few years ago I painted a picture in which I wanted to represent a typical boy. I searched for it for a long time, but, despite all the searches, the type I had conceived did not come across.

However, once in the spring, it was at the end of April, on a magnificent sunny day, I somehow wandered near the Tverskaya Zastava, and I began to come across factory and various artisans returning from the villages, after Easter, to their heavy summer work; whole groups of pilgrims, mostly peasant women, went to worship St. Sergius and the Moscow miracle workers; and at the very outpost, in an empty watch house with boarded up windows, on a dilapidated porch, I saw a large crowd of tired pedestrians.

Some of them sat and chewed some kind of bread; others, sweetly falling asleep, scattered under the warm rays of the brilliant sun. The picture was attractive! I began to peer into her details and, to the side, I noticed an old woman with a boy. The old woman was buying something from a fidgety peddler.

Coming closer to the boy, I was involuntarily struck by the type that I had been looking for for so long. I immediately struck up a conversation with the old woman and with him and asked them among other things: from where and where are they going? The old woman did not hesitate to explain that they were from the Ryazan province, were in New Jerusalem, and now they are making their way to Trinity-Sergius and would like to spend the night in Moscow, but they do not know where to take shelter. I volunteered to show them a place to sleep. We went together.

The old woman walked slowly, limping slightly. Her humble figure with a knapsack on her shoulders and with her head wrapped in something white was very pretty. All her attention was directed to the boy, who ceaselessly stopped and looked at everything that came across with great curiosity; the old woman, apparently, was afraid that he would not get lost.

Meanwhile, I was considering how to begin an explanation with her about my intention to write her companion. Without thinking of anything better, I began by offering her money. The old woman was perplexed and did not dare to take them. Then, out of necessity, I immediately told her that I really liked the boy and I would like to paint a portrait of him. She was even more surprised and even seemed to be timid.

I began to explain my desire, trying to speak as simply and clearly as possible. But no matter how I contrived, no matter how I explained, the old woman understood almost nothing, but only looked at me more and more incredulously. I then decided on the last resort and began to persuade him to come with me. To this the old woman agreed. Arriving at the workshop, I showed them the painting I had begun and explained what was the matter.

She seemed to understand, but nevertheless stubbornly refused my proposal, referring to the fact that they had no time, that it was a great sin, and besides, she also heard that people not only wither from this, but even die. As far as possible, I tried to assure her that this was not true, that these were just fairy tales, and as proof of my words, I cited the fact that both kings and bishops allow portraits to be painted from themselves, and St. the evangelist Luke was a painter himself, that there are many people in Moscow from whom portraits were painted, but they do not wither and do not die from this.

The old woman hesitated. I gave her a few more examples and offered her a good wage. She thought, thought, and finally, to my great joy, agreed to allow the portrait of her son to be taken, as it turned out later, twelve-year-old Vasya. The session started immediately. The old woman settled right there, nearby, and incessantly came and prettified her son, now straightening his hair, now pulling his shirt: in a word, she interfered terribly. I asked her not to touch or approach him, explaining that it slowed down my work.

She sat down quietly and began to talk about her life, all looking with love at her dear Vasya. From her story it could be seen that she was not at all as old as I thought at first sight; she was not many years old, but her life of work and grief had aged her before her time, and her tears extinguished her small, meek and affectionate eyes.

The session continued. Aunt Marya, that was her name, kept talking about her hard work and timelessness; of sickness and famine sent to them for their great transgressions; about how she buried her husband and children and was left with one consolation - her son Vasenka. And since then, for several years, she has been annually going to worship the great saints of God, and this time she took Vasya with her for the first time.

She told a lot of interesting, although not new, things about her bitter widowhood and peasant poverty. The session was over. She promised to come the next day and kept her promise. I continued my work. The boy sat well, but Aunt Marya again talked a lot. But then she began to yawn and cross her mouth, and finally, she completely dozed off. There was an imperturbable silence that lasted for about an hour.

Marya slept soundly and even snored. But suddenly she woke up and began to fuss about somehow uneasily, every minute asking me how long I would keep them, that it was time for them, that they would be late, the time was supposed to be long after noon and they should have been on the road long ago. Hastening to finish the head, I thanked them for their work, paid them off and saw them off. So we parted, satisfied with each other.

It's been about four years. I forgot both the old woman and the boy. The painting was sold long ago and hung on the wall of the currently famous gallery in the city of Tretyakov. Once at the end of Holy Week, returning home, I found out that some old village old woman had visited me twice, she waited a long time and, not having waited, wanted to come tomorrow. The next day, as soon as I woke up, they told me that the old woman was here and was waiting for me.

I went out and saw in front of me a small, hunched-over old woman with a large white headband, from under which a small face peeked out, cut with the smallest wrinkles; her thin lips were dry and seemed to be turned inside her mouth; little eyes looked sad. Her face was familiar to me: I had seen it many times, seen it in the paintings of great painters and in life.

This was not a simple village old woman, of whom we meet so many, no - she was a typical personification of boundless love and quiet sadness; he was something between the ideal old women in Raphael's paintings and our good old nannies, who are no longer in the world, and it is unlikely that there will ever be their like.

She stood leaning on a long stick, with a spirally carved bark; her unsheathed sheepskin coat was girded with some kind of braid; a rope from a knapsack thrown over her back pulled off the collar of her sheepskin coat and exposed her emaciated, wrinkled neck; her unnatural size bast shoes were covered with mud; all this shabby, more than once mended dress had a kind of sad look, and something bruised, suffering could be seen in her whole figure. I asked what she needed.

She moved her lips silently for a long time, fussed aimlessly, and finally, pulling out the eggs tied in a handkerchief from the body, she handed them to me, asking me to convincingly accept the gift and not to refuse her great request. Then she told me that she had known me for a long time, that three years ago she had been with me and I had copied her son, and, as far as she could, she even explained what kind of picture I had painted. I remembered the old woman, although it was difficult to recognize her: she had grown so old at that time!

I asked her what brought her to me? And as soon as I had time to utter this question, instantly the old woman's whole face seemed to stir, set into motion: her nose twitched nervously, her lips trembled, her little eyes blinked frequently, and suddenly stopped. She began some phrase, uttered the same word for a long time and incomprehensibly, and, apparently, did not have the strength to finish this word. “Father, my son,” she began for almost the tenth time, and tears flowed profusely and did not allow her to speak.

They flowed and in large drops quickly rolled down her wrinkled face. I gave her water. She refused. He offered her to sit down - she remained on her feet and wept all the time, wiping herself with the shaggy skirt of her rough short fur coat. Finally, after crying a little and calming down a little, she explained to me that her son, Vassenka, had contracted smallpox the previous year and had died. She told me with all the details about his serious illness and painful death, about how they lowered him into the damp earth, and with him buried all her joys and joys. She did not blame me for his death—no, it was the will of God, but it seemed to me myself that I was partly to blame for her grief.

I noticed that she thought the same, although she did not speak. And so, having buried her dear child, having sold all her belongings and having worked through the winter, she saved some money and came to me in order to buy a picture where her son was written off. She convincingly asked not to refuse her request. With trembling hands, she untied the handkerchief where her orphan's money was wrapped, and offered it to me. I explained to her that the painting was no longer mine and that it could not be bought. She became sad and began to ask if she could at least look at her.

I rejoiced her, saying that she could look, and appointed her to go with me the next day; but she refused, saying that she had already made a promise to stay with St. Saint Sergius, and, if possible, he will come the next day of Pascha. On the appointed day, she came very early and kept urging me to go faster so as not to be late. About nine o'clock we went to the city of Tretyakov. There I told her to wait, I myself went to the owner to explain to him what was the matter, and, of course, immediately received permission from him to show the picture. We walked through the richly decorated rooms, hung with paintings, but she paid no attention to anything.

Arriving in the room where the picture hung, which the old woman so convincingly asked to sell, I left it to her to find this picture. I confess, I thought that she would look for a long time, and perhaps not at all find the features dear to her; all the more so it could be assumed that there were a lot of paintings in this room.

But I was wrong. She looked around the room with her meek glance and quickly went to the picture where her dear Vasya really was depicted. Approaching the picture, she stopped, looked at it, and, clasping her hands, somehow unnaturally cried out:

"You are my father! You are my dear, here is your tooth knocked out!

"Troika". Craftsmen carrying water, 1866. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

"Troika". Craftsmen carrying water, 1866. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow - and with these words, like grass, cut by the swing of a scythe, fell to the floor. Having warned the man to leave the old woman alone, I went upstairs to the owner and, having been there for about an hour, returned downstairs to see what was happening there.

The next scene presented itself to my eyes: a man with wet eyes, leaning against the wall, pointed to the old woman and quickly went out, and the old woman was kneeling and praying to the picture. She prayed fervently and intently for the image of her dear and unforgettable son. Neither my arrival, nor the steps of the departed servant diverted her attention; she heard nothing, forgot about everything around her, and only saw in front of her what her broken heart was full of. I stopped, not daring to interfere with her holy prayer, and when it seemed to me that she had finished, I went up to her and asked: had she seen enough of her son?

The old woman slowly raised her meek eyes to me, and there was something unearthly in them. They shone with some kind of mother's delight at the unexpected meeting of their beloved and dead son. She looked inquiringly at me, and it was clear that she either did not understand me or did not hear me. I repeated the question, and she quietly whispered in response: "Can't you kiss him," and pointed to the image with her hand. I explained that this was not possible, by the tilted position of the painting.

Then she began to ask to be allowed to see enough of her dear Vasenka for the last time in her life. I left and, returning with the owner, Mr. Tretyakov, an hour and a half later, I saw her, as for the first time, still in the same position, on her knees in front of the picture. She noticed us, and a heavy sigh, more like a groan, escaped her chest. Crossing herself and bowing several more times to the ground, she said:

“Forgive me, my dear child, forgive me, my dear Vasenka!” - she got up and, turning to us, began to thank Mr. Tretyakov and me, bowing at her feet. G. Tretyakov gave her some money. She took them and put them in the pocket of her sheepskin coat. It seemed to me that she did it unconsciously.

For my part, I promised to paint a portrait of her son and send it to her in the village, for which I took her address. She fell at her feet again - it was no small effort to stop her from expressing such sincere gratitude; but, at last, she somehow calmed down and said goodbye. As she left the yard, she kept crossing herself and, turning around, bowed low to someone. I also took leave of Mr. Tretyakov and went home.

On the street, overtaking the old woman, I looked at her again: she walked quietly and seemed tired; her head was lowered on her chest; at times she spread her hands and talked to herself about something. A year later, I fulfilled my promise and sent her a portrait of her son, decorating it with a gilded frame, and a few months later I received a letter from her, where she informed me that “I hung the face of Vasenka to the icons and prays to God for his comfort and my health.”

The whole letter from beginning to end consisted of thanks. A good five or six years have passed, and even now the image of a little old woman with her small face, cut with wrinkles, with a rag on her head and with hardened hands, but with a great soul, often flashes before me. And this simple Russian woman in her wretched dress becomes a lofty type and ideal of maternal love and humility.

Are you alive now, my miserable? If yes, then I send you my heartfelt greetings. Or perhaps she has been resting for a long time in her peaceful rural cemetery, dotted with flowers in summer and covered with impenetrable snowdrifts in winter, next to her beloved son Vasenka.

The problem of child slavery and labor is not a problem of one city or one particular country or era - hard labor for children was ubiquitous, as well as hopelessness, poverty, hunger and cold of the peasants and the poor.

In our modern civilized world, this social problem, it would seem, has been solved, but this is only at first glance.

The child slave trade and the use of child labor have not disappeared, and according to the International Labor Organization, child slaves are the No. 3 business after the arms and drug trade. Child labor is particularly prevalent in Asia, where over 153 million children are illegally exploited; in Africa - more than 80 million and more than 17 million - in Latin America ...

Found an error? Select it and left click Ctrl+Enter.

“Lefty” - a summary of the work N

“Lefty” - a summary of the work N Turgenev, "Biryuk": a summary

Turgenev, "Biryuk": a summary Comedy A.N. Ostrovsky "Poverty is not a vice": a summary of the work

Comedy A.N. Ostrovsky "Poverty is not a vice": a summary of the work