KNIL: guarding the Dutch East Indies. Board of the East India Company in India

( Verenigde Oost— Indische Compagnie – VOC) – East India Company (OIC) (1602 – 1798); area of activity: Indonesia, Moluccas, Japan (Nagasaki coast), Iran, Bangladesh, Thailand (formerly Siam), Guangzhou, China (formerly Canton), Taiwan (before 1662 - Formosa), South India.

OIC was a joint stock company, it raised money for its activities through the issue and sale of shares (total capital amounted to 6.5 million guilders).

OIC action

The company was headed by 17 directors, the so-called XVII Lords (Heeren XVII). The goal of the OIC was not territorial conquest, but a trade monopoly. Colonial expansion in the Far East was made possible by the weakening of Portugal and due to constant competition with Spain and England - the latter of which was constantly increasing in strength. The following stages of this expansion can be distinguished:

1605 - conquest of the island of Ambon and then the following islands of the Moluccas Archipelago;

1619 - capture of part of the island of Java and the founding of the city of Batavia there;

1624 - capture of the island of Formosa;

1641 - capture of the Moluccas;

1658 – reverse seizure of Portuguese Ceylon;

1669 – capture of Makassar;

1682 - capture of the Bantam state.

In its colonial policy, the OIC followed three tactics:

- conquest and seizure of the entire territory;

- obtaining a monopoly on trade as a result of monopolistic agreements with local rulers;

- negotiating agreements in compliance with the law of free competition from trading companies other countries.

Tactic No. 2 was preferred.

The city of Batavia (now Jakarta), founded on the island of Java, was the center of the crossing routes, linking Largest cities in Asia.

OIC commercial routes

Replica of an eighteenth century ship Amsterdam

In trade, the Netherlands focused mainly on spices: pepper, cloves and nutmeg. In areas where the OIC exercised territorial control, supplies were subject to established quotas and the price was fixed. Suppliers who failed to fulfill their obligations were punished by death or slavery (they were forced to work on OIC plantations). When prices fell, the Dutch destroyed plantations and even the products themselves. In other areas, the Dutch received goods by agreement with local rulers, who received “protection” in return for supplies. Of course, they also benefited from cooperation with Dutch merchants.

Dutch Plantation in Bengal (India), Hendrick van Schuilenberg, 1665

The OIC also maintained trade relations with Persia, Siam, Japan and China. For two centuries, Dutch trade relations with Japan were based on the privilege of exclusivity. This exceptional position was achieved by avoiding the mistakes of the Dutch predecessors - the Spaniards and Portuguese. The Dutch were not trying to manipulate, but rather to be missionaries, and, in addition, they told the Japanese that they were not Catholics! But they were not allowed into the Empire of Japan, and the Dutch were forced to remain on the artificial island of Decima, which was built especially for them.

Interesting note

Once a year, Dutch merchants were allowed to enter the territory of the empire under the pretext of presenting tribute and respect to the emperor (the Dutch considered this to be payment of a tax) - the ban, at the same time, was formally supported. During this trip, merchants had the opportunity to conduct business meetings. These trips were described in interesting reports that have survived to this day.

The Dutch on the way to Edo to pay tribute to the emperor, 1727.

The same ban was in effect in China - direct trade began only in 1729, when Guangzhou became a place of exchange. (The Chinese were prejudiced against the Dutch because of the Portuguese, who made them look bad). One of the goods purchased in those countries and exported to Europe was tea (the Dutch were the first to bring Chinese tea to Europe, this happened in 1610). Even in the 18th century, Amsterdam was the largest market for this product. OIC also exported porcelain to Europe. Attempts to imitate the famous Chinese porcelain gave impetus to the creation of the famous Delft porcelain, which became very popular in Europe.

There were also strong trade ties with Arab countries - Saudi coffee was brought by the Dutch to Europe. The OIC did not escape the role of intermediary in trade between Asian countries, from which the company also received enormous benefits. How big the profit was can be tracked by the dividends paid to shareholders. In the best period (early 18th century) dividends were as much as 40%, then for a long time the commission was between 15-25%.

OIK warehouse in Oostenberg, Amsterdam

The decline of the OIC occurred during the crisis of the Republic of the United Provinces (at the end of the 18th century). Official bankruptcy was declared in 1798, and the East India Company then ceased to exist. Currently, its archives are stored in the state archive on many kilometers of shelves. Besides the weakness of the United Provinces, there were several other reasons for the decline of the OIC. Characteristic feature OIC colonization was that colonization did not lead to mass migration of the population of the Netherlands. Without  landed peasants tended to seek happiness in other European countries rather than in the Far East (Europe was underpopulated in the first half of the 17th century). They did not care about a quick and easy career in the colonies. OIC officials also refused to leave the Netherlands and often traveled to East Indies only for the conclusion of contracts. The salaries of minor officials, soldiers, sailors and other employees were so low that large-scale smuggling flourished, and illegal transactions, falsified accounts and corruption were common. The Republic of the United Provinces was unable to exercise effective control over its outlying lands. And this was her mistake - to squeeze out maximum profits with minimum costs. Therefore, the Dutch colonies were underfunded, had too little money for defense, and could not effectively counter their colonial competitors, mostly England. In the photo: Amsterdam OIC flag

landed peasants tended to seek happiness in other European countries rather than in the Far East (Europe was underpopulated in the first half of the 17th century). They did not care about a quick and easy career in the colonies. OIC officials also refused to leave the Netherlands and often traveled to East Indies only for the conclusion of contracts. The salaries of minor officials, soldiers, sailors and other employees were so low that large-scale smuggling flourished, and illegal transactions, falsified accounts and corruption were common. The Republic of the United Provinces was unable to exercise effective control over its outlying lands. And this was her mistake - to squeeze out maximum profits with minimum costs. Therefore, the Dutch colonies were underfunded, had too little money for defense, and could not effectively counter their colonial competitors, mostly England. In the photo: Amsterdam OIC flag

Despite the scarcity of the European population, especially decent white women (those who emigrated to the East Indies were usually shrews), the Dutch for a long time avoided racial mixing with the indigenous peoples. Then they gradually recognized marriages with local Christian women, and then with non-Christian women, but did not allow them and their children to enter the territory of the republic. They were not Dutch. Those born in Asia, regardless of race, were always inferior to Europeans and had to give way to them in obtaining jobs and positions.

The OIC was also active in Africa, as described in Chapter .

II Dutch Indies. 19th century

After the fall of the OIC, the composition of the Dutch colonies changed. Ceylon and Malaya (in 1824) were irrevocably ceded to England. The British failed to maintain control over the islands of Sumatra and Java, which they captured in 1811 for only three years, and in 1814 they were returned to the Netherlands. Since then, the former East Indies began to be called the Dutch Indies. From the creation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815 until 1848, the sovereignty of the colonies was represented by the king, and from 1848 this function was transferred to the States General.

Dutch India

The fall of the OIC and the abolition of the trade monopoly, along with increasing competition from England, forced the Netherlands to define new forms of exploitation of the Dutch Indies. From this time on, peasants, subject to the new cultuurstelsel (cultivation system) imposed by the Dutch, had to use 1/5 of their land for cultivating plants, while landless people had to  were to work on plantations for 1/5 of the year. This system proved to be very effective and profits from the sale of sugar and coffee increased significantly. (Income from investments in the colonies was spent in the Netherlands.) But in the mid-19th century, under the influence of liberal ideas, a certain part of Dutch society demanded reform in the colonies: reductions state control and increased freedom for private enterprise, which led to the legalization of private capital. This was introduced in 1870 by government decree, which was in force until 1925. A significant change was the replacement of compulsory supplies of agricultural products with taxes; poll taxes, land taxes and indirect taxes were introduced. In the photo: collecting resin from a damarov acacia tree, o. Celebes.

were to work on plantations for 1/5 of the year. This system proved to be very effective and profits from the sale of sugar and coffee increased significantly. (Income from investments in the colonies was spent in the Netherlands.) But in the mid-19th century, under the influence of liberal ideas, a certain part of Dutch society demanded reform in the colonies: reductions state control and increased freedom for private enterprise, which led to the legalization of private capital. This was introduced in 1870 by government decree, which was in force until 1925. A significant change was the replacement of compulsory supplies of agricultural products with taxes; poll taxes, land taxes and indirect taxes were introduced. In the photo: collecting resin from a damarov acacia tree, o. Celebes.

During the presence of the Dutch in the Dutch East Indies, protests from the local population periodically broke out. In 1825 on the island. Java experienced an uprising against the colonists, local rulers and Chinese traders. The revolt lasted until 1830, but was brutally suppressed, with approximately 200,000 Javanese killed. Another rebellion, involving Sumatra, Sulawesi and Bali, was stopped by punitive expeditions. Local wars and conflicts were common.

1873 was the year of the sudden outbreak of war with the Sultanate of Aceh, located in northern Sumatra. In the 16th and 17th centuries it was the most important country in the region. The Sultanate used to support piracy, but as long as it did not affect the most important sea routes, the OIC did not care much about it. The situation changed with the creation of the Suez Canal, which meant that ships had to pass by the coast of Aceh. This forced the Dutch to conquer the sultanate, which led to a long and costly war (1873 - 1903), eventually the sultanate fell and the Dutch lost control of the entire island.

Dutch officers in Aceh, 1900

From about 1910, the Netherlands controlled the entire Malay Archipelago, but the status of its territories varied. More than half of the territory was included in the Dutch Indies, the rest of the territory had formal autonomy. Owning these colonies had both pros and cons. Private business benefited from the trade in sugar, tobacco, tin, oil and coal. Great profit opportunities in trade, industry, services and agriculture, as well as investment in infrastructure, have attracted residents of the Netherlands. Approximately 90,000 Dutch moved here from Europe after the First World War. On the other hand, for the state this meant huge costs for defense and warfare (the war with the Aceh Sultanate was especially expensive), although the state only partially participated in making a profit. The situation in the Dutch treasury only improved after the tax reform of 1908.

At the end of the 19th century, part of Dutch society thought about the moral aspect of the exploitation of the Far Eastern colonies, people came to the conclusion that the state had a serious moral duty in front of those colonies. It was estimated that the state profit from the use of the colonies was approximately 1.5 billion guilders. This is how the so-called “ethical policy” arose. The new policy meant the need to improve living conditions for the local population through accessible education, healthcare, improved communications, the establishment of a modern system of government and justice, etc. However, this was not done without interest for the Netherlands itself, since a better standard of living for the local population was beneficial for the sale of Dutch goods.

Interesting fact:

Despite intensive commercial contacts with the colonies, the Northern Netherlands for a long time did not consider it necessary to modernize  b your fleet - replace sailing ships to ships. The goods were delivered regularly and there was no reason to rush. In 1858 the Dutch merchant fleet consisted of 2,397 sailing ships and only 41 steamships; in 1900 there were still 432 sailing boats in use. But there were reasons for this. Steam engines required coal refueling stations along the way and in Indonesia itself. These stations also required protection and maintenance. Due to difficult working conditions, it was difficult to recruit a team. Moreover, the coal ships had to return empty, as they were too dirty to transport food: tea, coffee, rice, spices, etc. Thus, on remote routes, sailing ships were cheaper than steamships. In the photo: a ship sailing to the colony.

b your fleet - replace sailing ships to ships. The goods were delivered regularly and there was no reason to rush. In 1858 the Dutch merchant fleet consisted of 2,397 sailing ships and only 41 steamships; in 1900 there were still 432 sailing boats in use. But there were reasons for this. Steam engines required coal refueling stations along the way and in Indonesia itself. These stations also required protection and maintenance. Due to difficult working conditions, it was difficult to recruit a team. Moreover, the coal ships had to return empty, as they were too dirty to transport food: tea, coffee, rice, spices, etc. Thus, on remote routes, sailing ships were cheaper than steamships. In the photo: a ship sailing to the colony.

III 20th century – on the way to independence

At the beginning of the 20th century, dark clouds began to gather over the Dutch leadership of the Dutch East Indies. This was due to the awakening of national consciousness and the increase in anti-imperialist and revolutionary sentiment (as echoes October revolution 1917). Economic and social changes have produced big impact to these territories. Feudal relations were replaced by capitalism, and industrial development led to the birth of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, which each began to develop in its own direction. In 1927, the Indonesian National Party was founded.

Dutch colonial residence

The colonial government, representing the interests of the Dutch capital and having a thriving business there, put up strong resistance to the liberation tendencies of the Indonesians. Although political reforms were introduced, the capital maintained strict control over the colonies. Any action against the colonial authorities (for example, the uprising in 1926 on the island of Java and in 1927 on the island of Sumatra) was severely punished - imprisonment, exile in camps, and even death penalty. In this situation, Indonesians began to sympathize with Japan, which was seen as a liberator (on the eve of World War II, Japan intensified its economic expansion in the archipelago).

After the outbreak of World War II, the Dutch Indies became the site of the war with Japan. In response to a Japanese request, which was rejected by the Dutch government-in-exile, the Netherlands declared war on Japan in December 1941. From 1942, the Japanese army successively occupied Dutch-held territory, leading to the surrender of the Royal Netherlands and Indian Army, signed on March 9, 1942. From this moment on, the situation for the Dutch population became critical. The Dutch were exiled to camps, soldiers were forced to slave labor. Several thousand civilians and prisoners could not survive it.

Capture of Governor General Tjard van Starkenborgh Stachoover, 1942

Some Indonesians, including former President Sukarno, saw Japanese rule as a chance to gain independence, which they eventually received. Military defeat Japan led to the recognition of Indonesian independence, which was declared on August 17, 1945.

For a long time, the Netherlands did not want to accept the loss of this colony and tried to restore the previous status quo through military force. However, the first attempts to solve the problem were made through negotiations and signing peace treaties. One such treaty provided a new status quo based on the concept of a federation - the United States of Indonesia (part of the Kingdom), consisting of the Republic of Indonesia (Java, Madura, Sumatra) and the Greater East (Borneo and other islands under the direct rule of the Netherlands). The corresponding agreement was signed on November 15, 1946 in Linggajati, but this did not satisfy either party. (The Greater East and Moluccas voted to remain in the Kingdom as they did not want to come under Javanese leadership.)

Dutch soldiers checking documents of women of Batavia, 1946

In the following years (1947 and 1948), the Netherlands initiated two military interventions, but, despite signing new agreements, were unable to stop the emancipation of Indonesia. The last formal link between the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Republic of Indonesia (founded 5 January 1949) was the Netherlands-Indonesian Union (signed 7 May 1949), under which the Netherlands exercised strict control foreign policy, finance and military power in western New Guinea. This was when Batavia was renamed Jakarta, which became the capital of the republic. Indonesia dissolved the union in 1954, and Dutch property (public and private) was nationalized in 1957.

The longest battle was fought by the Netherlands to maintain control of western New Guinea, which led to the severance of diplomatic relations between the countries in 1960.

Dutch New Guinea, 1916

In 1961, the disputed territory was captured by the Indonesians. In 1962, the territory was handed over to the UN provisional government, to be incorporated into Indonesia as West Irian in 1963. Since the late 1960s, especially after the fall of Sukarno, relations between Indonesia and the Kingdom of the Netherlands began to normalize, as evidenced by the visit of Queen Juliana in 1971.

The legacy left by the Dutch in this territory is enormous, but perhaps even more can be traced in material terms. This topic was discussed separately in the chapter . It should be noted here that the Dutch were a factor in uniting the various kingdoms of ancient East India, and the territory of modern Indonesia coincides with the former Dutch Indies.

Bandung, De Groot Postweg Oos – road built by the Dutch

Photos: Wikimedia commons, Tropenmuseum collection

Plan

Introduction

1 Background

2 General chronology

2.1 Foundation

2.2 Territorial expansion

2.3 Islamic resistance

2.4 Fall of the Dutch East Indies

Bibliography

Introduction

Dutch East Indies (Dutch. Nederlands-Indië; Indon. Hindia-Belanda) - Dutch colonial possessions on the islands of the Malay Archipelago and in the western part of the island of New Guinea. It was formed in 1800 as a result of the nationalization of the Dutch East India Company. Existed until the Japanese occupation in March 1942. Also sometimes called colloquially and informally Netherlandish (or Dutch) India. It should not be confused with the Dutch Indies, a Dutch colonial possession on the Hindustan Peninsula. Like other colonial entities, the Dutch East Indies were created in intense competition both with local state formations and with other colonial powers (Great Britain, Portugal, France, Spain). For a long time it had a predominantly thalassocratic character, representing a series of coastal trading posts and outposts surrounded by the possessions of local Malay sultanates. The conquests of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as well as the use of powerful economic exploitation mechanisms, allowed the Dutch to unite most of the archipelago under the rule of their crown. The Dutch East Indies, with its rich reserves of oil and other minerals, were considered "the jewel in the crown of the Dutch colonial empire."1. Background

2. General chronology

- 1859: annexation of 2/3 of the territory of Portuguese Indonesia, excluding the East Timor region.

- 1942-1945: Japanese occupation of Indonesia

2.1. Base

During the Napoleonic Wars, the territory of Holland itself was captured by France, and all Dutch colonies automatically became French. As a result, the colony was ruled by a French governor-general from 1808 to 1811. In 1811-1816, during the ongoing Napoleonic Wars, the territory of the Dutch East Indies was captured by England, which feared the strengthening of France (by this time Great Britain had also managed to occupy the Cape Colony, the most important trade link between the Netherlands and Indonesia). The power of the Dutch colonial empire was undermined, but England needed a Protestant ally in the fight against the Catholic old colonial powers of France, Spain and Portugal. Therefore, in 1824, the occupied territory was returned to Holland by an Anglo-Dutch agreement in exchange for Dutch colonial possessions in India. In addition, the Malacca Peninsula passed to England. The resulting border between British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies remains to this day the border between Malaysia and Indonesia.2.2. Territorial expansion

The capital of the Dutch East Indies was Batavia, now Jakarta is the capital of Indonesia. Although the island of Java was controlled by the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch colonial administration for 350 years, from the time of Kun, full control over most of the Dutch East Indies, including the islands of Borneo, Lombok and western New Guinea, was established only at the beginning of the 20th century. .2.3. Islamic resistance

The indigenous population of Indonesia, supported by the internal stability of Islamic institutions, offered significant resistance to the Dutch East India Company and later to the Dutch colonial administration, which weakened Dutch control and tied up its military forces. The longest conflicts were the Padri War in Sumatra (1821-1838), the Java War (1825-1830) and the bloody Thirty Years' War in the Sultanate of Aceh (north West Side Sumatra), which lasted from 1873 to 1908. In 1846 and 1849 the Dutch undertook unsuccessful attempts conquer the island of Bali, which was conquered only in 1906. The natives of West Papua and most of the interior mountainous areas were only subdued in the 1920s. A significant problem for the Dutch was also quite strong piracy (Malay, Chinese, Arab, European) in these waters, which continued until mid-19th V.In 1904-1909, during the reign of Governor General J.B. Van Hoetz, the power of the Dutch colonial administration extended to the entire territory of the Dutch East Indies, thus laying the foundations of the modern Indonesian state. Southwest Sulawesi was occupied in 1905-1906, Bali in 1906 and western New Guinea in 1920.

2.4. Fall of the Dutch East Indies

On January 10, 1942, Japan, in need of the minerals that the Dutch East Indies were rich in (primarily oil), declared war on the Kingdom of the Netherlands. During the Operation in the Dutch East Indies, the territory of the colony was completely captured by Japanese troops by March 1942.The fall of the Dutch East Indies also meant the end of the Dutch colonial empire. Already on August 17, 1945, after liberation from Japan, the Republic of Indonesia was proclaimed, which Holland recognized in 1949 at the end of the Indonesian War of Independence.

Bibliography:

In the 17th century, the Netherlands became one of the largest sea powers Europe. Several trading companies responsible for the country's overseas trade and essentially engaged in colonial expansion in the South and South-East Asia, in 1602 were merged into the Dutch East India Company. The city of Batavia (now Jakarta) was founded on the island of Java, becoming an outpost of Dutch expansion in Indonesia. By the end of the 60s of the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company had become a serious organization with its own merchant and military fleet and ten thousand private armed forces. However, the defeat of the Netherlands in the confrontation with the more powerful British Empire contributed to the gradual weakening and collapse of the Dutch East India Company. In 1798, the company's property was nationalized by the Netherlands, which at that time bore the name of the Batavian Republic.

Indonesia under Dutch rule

By the beginning of the 19th century, the Dutch East Indies was, first of all, a network of military trading posts on the coast of the Indonesian islands, but the Dutch practically did not advance deeper into the latter. The situation changed during the first half of the 19th century century. By the middle of the 19th century, the Netherlands, having finally suppressed the resistance of local sultans and rajas, subjugated the most developed islands of the Malay Archipelago, now part of Indonesia, under their influence. In 1859, 2/3 of the possessions in Indonesia that previously belonged to Portugal were also included in the Dutch East Indies. Thus, the Portuguese lost the competition for influence in the islands of the Malay Archipelago to the Netherlands.

In parallel with the displacement of the British and Portuguese from Indonesia, colonial expansion continued into the interior of the islands. Naturally, the Indonesian population met colonization with desperate and long-term resistance. To maintain order in the colony and its defense from external opponents, among which there could well be colonial troops of European countries competing with the Netherlands for influence in the Malay Archipelago, it was necessary to create armed forces intended directly for operations within the territory of the Dutch East Indies. Like other European powers that had overseas territorial possessions, The Netherlands began to form colonial troops.

On March 10, 1830, a corresponding royal decree was signed on the creation of the Royal Dutch East Indian Army (Dutch abbreviation - KNIL). Like the colonial troops of a number of other states, the Royal Dutch East Indian Army was not part of the armed forces of the metropolis. The main tasks of the KNIL were to conquer the interior of the Indonesian islands, fight rebels and maintain order in the colony, and protect colonial possessions from possible attacks from external opponents. IN during the XIX- XX centuries colonial troops of the Dutch East Indies participated in a number of campaigns in the Malay Archipelago, including the Padri Wars in 1821-1845, the Java War of 1825-1830, the suppression of resistance on the island of Bali in 1849, the Acehnese War in northern Sumatra in 1873-1904, the annexation of Lombok and Karangsem in 1894, the conquest of the southwestern part of the island of Sulawesi in 1905-1906, the final “pacification” of Bali in 1906-1908, the conquest of West Papua in 1920- e years

The "Pacification" of Bali in 1906-1908 by colonial forces received widespread coverage in the world press due to the atrocities committed by Dutch soldiers against Balinese independence fighters. During the "Bali Operation" of 1906, the two kingdoms of Southern Bali - Badung and Tabanan - were finally subdued, and in 1908 the Dutch East Indian Army put an end to the largest state on the island of Bali - the Klungkung Kingdom. Incidentally, one of the key reasons for the active resistance of the Balinese rajahs to the Dutch colonial expansion became the desire of the East Indies authorities to control the opium trade in the region.

When the conquest of the Malay Archipelago could be considered a fait accompli, the use of the KNIL continued, primarily in police operations against rebel groups and large gangs. Also, the tasks of the colonial troops included the suppression of constant mass popular performances, which broke out in various parts of the Dutch East Indies. That is, in general, they performed the same functions that were inherent in the colonial troops of other European powers based in African, Asian and Latin American colonies.

Recruitment of the East Indian Army

The Royal Dutch East Indian Army had its own recruitment system. Thus, in the 19th century, the recruitment of colonial troops was carried out primarily through Dutch volunteers and mercenaries from other European countries, primarily the Belgians, Swiss, and Germans. It is known that he was recruited for service on the island of Java French poet Arthur Rimbaud. When the colonial administration waged a long and difficult war against the Muslim Sultanate of Aceh on the northwestern tip of the island of Sumatra, the number of colonial troops reached 12,000 soldiers and officers recruited in Europe.

Since Aceh was considered the most religiously “fanatical” state in the Malay Archipelago, which had a long tradition of political sovereignty and was considered the “stronghold of Islam” in Indonesia, the resistance of its inhabitants was especially strong. Realizing that the colonial troops manned in Europe, due to their numbers, could not cope with the Acehnese resistance, the colonial administration began recruiting natives for military service. 23 thousand Indonesian soldiers were recruited, primarily natives of Java, Ambon and Manado. In addition, African mercenaries from the Coast arrived in Indonesia Ivory and the territory of modern Ghana - the so-called “Dutch Guinea”, which remained under Dutch rule until 1871.

The end of the Aceh War also contributed to the cessation of the practice of hiring soldiers and officers from other European countries. The Royal Dutch East Indian Army began to be staffed by residents of the Netherlands, Dutch colonists in Indonesia, Dutch-Indonesian mestizos and Indonesians themselves. Although the decision was made not to send Dutch soldiers from the mother country to serve in the Dutch East Indies, volunteers from the Netherlands still served in the colonial forces.

In 1890, a special department was created in the Netherlands itself, whose competence included the recruitment and training of future soldiers of the colonial army, as well as their re-rehabilitation and adaptation to peaceful life in Dutch society after the end of contract service. As for the natives, the colonial authorities gave preference when recruiting for military service to the Javanese as representatives of the most civilized ethnic group, in addition to everything, they were included in the colony early (1830, while many islands were finally colonized only a century later - in the 1920s. ) and the Ambonians - as a Christianized ethnic group under the cultural influence of the Dutch.

In addition, African mercenaries were also recruited for service. The latter were recruited primarily among representatives of the Ashanti people living in the territory of modern Ghana. Residents of Indonesia nicknamed the African riflemen who served in the Royal Dutch East Indian Army as “Black Dutch”. The skin color and physical characteristics of African mercenaries terrified the local population, but the high cost of transporting soldiers from the west coast of Africa to Indonesia ultimately contributed to the gradual abandonment of the colonial authorities of the Dutch East Indies from recruiting the East Indian army, including African mercenaries.

The Christian part of Indonesia, primarily the South Molluc Islands and Timor, has traditionally been considered the most reliable supplier of military personnel for the Royal Dutch East Indian Army. The most reliable contingent were the Ambonians. Despite the fact that the inhabitants of the Ambon Islands early XIX resisted Dutch colonial expansion for centuries, they eventually became the most reliable allies of the colonial administration among the native population. This was due to the fact that, firstly, at least half of the Ambonians converted to Christianity, and secondly, the Ambonians strongly mixed with other Indonesians and Europeans, which turned them into the so-called. "colonial" ethnic group. By taking part in suppressing the uprisings of Indonesian peoples on other islands, the Ambonese earned the full trust of the colonial administration and, thus, secured privileges for themselves, becoming the category of local population closest to the Europeans. In addition to military service, the Ambonese were actively involved in business, many of them became rich and Europeanized.

The Christian part of Indonesia, primarily the South Molluc Islands and Timor, has traditionally been considered the most reliable supplier of military personnel for the Royal Dutch East Indian Army. The most reliable contingent were the Ambonians. Despite the fact that the inhabitants of the Ambon Islands early XIX resisted Dutch colonial expansion for centuries, they eventually became the most reliable allies of the colonial administration among the native population. This was due to the fact that, firstly, at least half of the Ambonians converted to Christianity, and secondly, the Ambonians strongly mixed with other Indonesians and Europeans, which turned them into the so-called. "colonial" ethnic group. By taking part in suppressing the uprisings of Indonesian peoples on other islands, the Ambonese earned the full trust of the colonial administration and, thus, secured privileges for themselves, becoming the category of local population closest to the Europeans. In addition to military service, the Ambonese were actively involved in business, many of them became rich and Europeanized.

Javanese, Sundanese, Sumatran soldiers who professed Islam received less pay compared to representatives of the Christian peoples of Indonesia, which was supposed to encourage them to accept Christianity, but in reality it only sowed internal contradictions among the contingent of military personnel, based on religious hostility and material competition . As for the officer corps, it was staffed almost exclusively by the Dutch, as well as European colonists living on the island and Indo-Dutch mestizos. The strength of the Royal Dutch East Indian Army at the beginning of World War II was about 1,000 officers and 34,000 non-commissioned officers and soldiers. At the same time, 28,000 military personnel were representatives of the indigenous peoples of Indonesia, 7,000 were Dutch and representatives of other non-indigenous peoples.

Mutinies in the colonial fleet

The multi-ethnic composition of the colonial army repeatedly became a source of numerous problems for the Dutch administration, but it could not change the system of recruiting the armed forces stationed in the colony. There would simply not be enough European mercenaries and volunteers to cover the needs of the Royal Dutch East Indian Army in private and non-commissioned officers. Therefore, one had to come to terms with serving in the ranks of the colonial troops of Indonesians, many of whom, for obvious reasons, were not really loyal to the colonial authorities. The most conflict-prone contingent were military sailors.

As in many other states, including Russian Empire, the sailors were more revolutionary than the soldiers of the ground forces. This was explained by the fact that people with more high level education and vocational training - as a rule, former workers of industrial enterprises and transport. As for the Dutch fleet stationed in Indonesia, on the one hand, Dutch workers served on it, among whom were followers of social democratic and communist ideas, and on the other hand, representatives of the small Indonesian working class, who learned in constant communication with revolutionary ideas with his Dutch colleagues.

In 1917, a powerful uprising of sailors and soldiers broke out at the naval base in Surabaya. The sailors created the Councils of Sailors' Deputies. Of course, the uprising was harshly suppressed by the colonial military administration. However, the history of performances at naval facilities in the Dutch East Indies did not stop there. In 1933, a mutiny broke out on the battleship De Zeven Provincial (Seven Provinces). On January 30, 1933, at the Morocrembangan naval base, a sailor uprising took place against low pay and discrimination by Dutch officers and non-commissioned officers, suppressed by the command. Participants in the uprising were arrested. During exercises in the area of the island of Sumatra, the revolutionary committee of sailors created on the battleship "De Zeven Provincien" decided to raise an uprising in solidarity with the sailors of Morocrembangan. The Indonesian sailors were joined by a number of Dutchmen, primarily those associated with communist and socialist organizations.

On February 4, 1933, while the battleship was off base at Kotaradia, the ship's officers went ashore for a banquet. At this moment, the sailors, led by helmsman Kavilarang and engineer Bosshart, neutralized the remaining watch officers and non-commissioned officers and captured the ship. The battleship put to sea and headed for Surabaya. At the same time, the ship's radio station broadcast the demands of the rebels (by the way, they did not contain a touch of politics): to raise the salaries of sailors, to stop discrimination against native sailors by Dutch officers and non-commissioned officers, to release the arrested sailors who took part in the riot at the Morocrembangan naval base (this riot took place a few days earlier, January 30, 1933).

To suppress the uprising, a special group of ships was formed, consisting of the light cruiser Java and the destroyers Piet Hein and Everest. The group's commander, Commander Van Dulm, led it to intercept the battleship De Zeven Provincien in the Sunda Islands area. Simultaneously command naval forces decided to transfer to coastal units or demobilize all Indonesian sailors and staff the crew exclusively with Dutchmen. On February 10, 1933, the punitive group managed to overtake the rebel battleship. The marines who landed on deck arrested the leaders of the uprising. The battleship was towed to the port of Surabaya. Kavilarang and Bosshart, like other leaders of the uprising, received serious prison sentences. The uprising on the battleship De Zeven Provincien went down in the history of the Indonesian national liberation movement and became widely known outside Indonesia: even in the Soviet Union, years later, a separate work was published devoted to a detailed description of the events on the battleship of the East India squadron of the Dutch naval forces .

Before World War II

By the time of the outbreak of World War II, the number of the Royal Dutch East Indian Army stationed in the Malay Archipelago reached 85 thousand people. In addition to 1,000 officers and 34,000 soldiers and non-commissioned officers of the colonial forces, this number included military personnel and civilian personnel of the territorial security and militia units. IN structurally The Royal Dutch East Indian Army consisted of three divisions: six infantry regiments and 16 infantry battalions; a combined brigade of three infantry battalions stationed in Barisan; a small combined brigade consisting of two marine battalions and two cavalry squadrons. In addition, the Royal Dutch East Indian Army had a howitzer battalion (105 mm heavy howitzers), an artillery battalion (75 mm field guns) and two mountain artillery battalions (75 mm mountain guns). A “Mobile Squad” was also created, armed with tanks and armored vehicles - we will talk about it in more detail below.

The colonial authorities and military command took frantic measures to modernize the units of the East Indian Army, hoping to turn it into a force capable of defending Dutch sovereignty in the Malay Archipelago. It was clear that in the event of war, the Royal Dutch East Indian Army would have to face the Japanese imperial army- an enemy many times more serious than rebel groups or even the colonial troops of other European powers.

The colonial authorities and military command took frantic measures to modernize the units of the East Indian Army, hoping to turn it into a force capable of defending Dutch sovereignty in the Malay Archipelago. It was clear that in the event of war, the Royal Dutch East Indian Army would have to face the Japanese imperial army- an enemy many times more serious than rebel groups or even the colonial troops of other European powers.

In 1936, trying to protect itself from possible aggression from Japan (the hegemonic claims of the “country rising sun" for the role of overlord of Southeast Asia had long been known), the authorities of the Dutch East Indies decided to modernize the restructuring of the Royal Dutch East Indian Army. It was decided to form six mechanized brigades. The brigade was to include motorized infantry, artillery, reconnaissance units and a tank battalion.

The military command believed that the use of tanks would significantly strengthen the power of the East Indian army and make it a serious adversary. Seventy Vickers light tanks were ordered from Great Britain just on the eve of the outbreak of World War II and fighting prevented the delivery of most of the shipment to Indonesia. Only twenty tanks arrived. The British government confiscated the rest of the shipment for its own use. Then the authorities of the Dutch East Indies turned to the United States for help. An agreement was concluded with the Marmon-Herrington company, which was engaged in the supply of military equipment to the Dutch East Indies.

According to this agreement, signed in 1939, it was planned to deliver a huge number of tanks by 1943 - 628 units. These were the following vehicles: CTLS-4 with a single turret (crew - driver and gunner); triple CTMS-1TBI and medium quadruple MTLS-1GI4. The end of 1941 was marked by the beginning of the acceptance of the first batches of tanks in the United States. However, the very first ship sent from the United States with tanks on board ran aground when approaching the port, as a result of which most (18 out of 25) of the vehicles were damaged and only 7 vehicles were usable without repair procedures.

The creation of tank units required the Royal Dutch East Indian Army to have trained military personnel capable of professional qualities serve in tank units. By 1941, when the Dutch East Indies received the first tanks, the East Indian Army had trained 30 officers and 500 non-commissioned officers and soldiers in the armored field. They were trained on previously purchased English Vickers. But even for one tank battalion, despite the presence of personnel, there were not enough tanks.

Therefore, the 7 tanks that survived the unloading of the ship, together with 17 Vickers purchased in Great Britain, formed the “Mobile Detachment”, which included a tank squadron, a motorized infantry company (150 soldiers and officers, 16 armored trucks), a reconnaissance platoon ( three armored vehicles), an anti-tank artillery battery and a mountain artillery battery. During the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies, the Mobile Force, under the command of Captain G. Wulfhost, together with the 5th Infantry Battalion of the East Indian Army, entered into battle with the Japanese 230th Infantry Regiment. Despite initial success, the Mobile Unit was eventually forced to retreat, leaving 14 men killed, 13 tanks, 1 armored car and 5 armored personnel carriers disabled. After this, the command redeployed the detachment to Bandung and no longer sent it into combat operations until the surrender of the Dutch East Indies to the Japanese.

The Second World War

After the Netherlands was occupied Hitler's Germany, the military-political situation of the Dutch East Indies began to rapidly deteriorate - after all, the channels of military and economic assistance from the metropolis were blocked, and on top of that, Germany, which until the end of the 1930s remained one of the key military-trading partners of the Netherlands, now, understandably reasons, it ceased to be such. On the other hand, Japan has become more active, having long been planning to “take control” of almost the entire Asia-Pacific region. Japanese imperial fleet delivered units of the Japanese army to the shores of the islands of the Malay Archipelago.

The very progress of the operation in the Dutch East Indies was quite rapid. Flights began in 1941 Japanese aviation over Borneo, after which units invaded the island Japanese troops, whose goal was to seize oil enterprises. Then the airport on the island of Sulawesi was captured. A force of 324 Japanese defeated 1,500 Marines Royal Dutch East Indian Army. In March 1942, battles began for Batavia (Jakarta), which ended on March 8 with the surrender of the capital of the Dutch East Indies. General Pooten, who commanded its defense, capitulated along with a garrison numbering 93,000 people.

During the 1941-1942 campaign. Almost the entire East Indian army was defeated by the Japanese. Dutch military personnel, as well as soldiers and non-commissioned officers from among the Christian ethnic groups of Indonesia, were interned in prisoner of war camps, and up to 25% of prisoners of war died. A small number of soldiers, mainly from among the Indonesian peoples, were able to escape into the jungle and continue guerrilla warfare against the Japanese occupiers. Some units managed to hold out completely independently, without any help from the allies, until Indonesia was liberated from Japanese occupation.

During the 1941-1942 campaign. Almost the entire East Indian army was defeated by the Japanese. Dutch military personnel, as well as soldiers and non-commissioned officers from among the Christian ethnic groups of Indonesia, were interned in prisoner of war camps, and up to 25% of prisoners of war died. A small number of soldiers, mainly from among the Indonesian peoples, were able to escape into the jungle and continue guerrilla warfare against the Japanese occupiers. Some units managed to hold out completely independently, without any help from the allies, until Indonesia was liberated from Japanese occupation.

Another part of the East Indian army managed to cross to Australia, after which it was attached to the Australian forces. At the end of 1942, there was an attempt to reinforce the Australian special forces, who were waging a guerrilla fight against the Japanese in East Timor, with Dutch soldiers from the East Indian army. However, 60 Dutch in Timor died. In addition, in 1944-1945. small Dutch units took part in the fighting in Borneo and the island of New Guinea. Under the operational command of the Royal Australian Air Force, four Dutch East Indies squadrons were formed from Royal Dutch East Indies Army Air Force pilots and Australian ground personnel.

As for the Air Force, the aviation of the Royal Dutch East Indian Army was initially seriously inferior to the Japanese in terms of equipment, which did not prevent the Dutch pilots from fighting with dignity, defending the archipelago from Japanese fleet, and then transfer to the Australian contingent. During the Battle of Semplak on January 19, 1942, Dutch pilots in 8 Buffalo aircraft fought against 35 Japanese aircraft. As a result of the collision, 11 Japanese and 4 Dutch aircraft were shot down. Among the Dutch aces, it is worth noting Lieutenant August Deibel, who during this operation shot down three Japanese fighters. Lieutenant Deibel managed to go through the entire war, surviving after two wounds, but death found him in the air after the war - in 1951 he died at the controls of a fighter plane in a plane crash.

When the East Indian Army surrendered, it was air Force The Dutch East Indies remained the most combat-ready unit that came under Australian command. Three squadrons were formed - two squadrons of B-25 bombers and one of P-40 Kittyhawk fighters. In addition, three Dutch squadrons were created as part of the British Air Force. The RAF was controlled by the 320th and 321st bomber squadrons and the 322nd fighter squadron. The latter, to this day, remains part of the Dutch Air Force.

Post-war period

The end of World War II was accompanied by the growth of the national liberation movement in Indonesia. Having freed themselves from Japanese occupation, the Indonesians no longer wanted to return to the rule of the mother country. The Netherlands, despite frantic attempts to keep the colony under its rule, were forced to make concessions to the leaders of the national liberation movement. However, the Royal Dutch East Indian Army was rebuilt and continued to exist for some time after World War II. Its soldiers and officers took part in two major military campaigns to restore colonial order in the Malay Archipelago in 1947 and 1948. However, all the efforts of the Dutch command to preserve sovereignty in the Dutch East Indies were in vain and on December 27, 1949, the Netherlands agreed to recognize the political sovereignty of Indonesia.

On July 26, 1950, it was decided to disband the Royal Dutch East Indian Army. By the time of its disbandment, 65,000 soldiers and officers were serving in the Royal Dutch East India Army. Of these, 26,000 were recruited into the Indonesian Republican Armed Forces, the remaining 39,000 were demobilized or transferred to serve in the Dutch Armed Forces. Native soldiers were given the option of demobilization or continued service in the armed forces of a sovereign Indonesia.

However, here again interethnic contradictions made themselves felt. The new armed forces of sovereign Indonesia were dominated by Muslim Javanese - veterans of the national liberation struggle, who always had a negative attitude towards Dutch colonization. The main contingent of the colonial troops was represented by Christianized Ambonese and other peoples of the South Mollucan Islands. Inevitable tensions arose between the Ambonese and Javanese, leading to conflicts in Makassar in April 1950 and an attempt to create an independent Republic of the South Moluccas in July 1950. Republican troops managed to suppress the Ambonese protests by November 1950.

After this, more than 12,500 Ambonese serving in the Royal Dutch East Indian Army, as well as their families, were forced to emigrate from Indonesia to the Netherlands. Some Ambonese emigrated to Western New Guinea (Papua), which remained under Dutch rule until 1962. The desire of the Ambonians, who were in the service of the Dutch authorities, to emigrate was explained very simply - they feared for their lives and safety in post-colonial Indonesia. As it turned out, it was not in vain: periodically, serious unrest breaks out on the Molluk Islands, the cause of which is almost always conflicts between the Muslim and Christian populations.

Background

Fall of the Dutch East Indies

see also

- Film Max Havelaar

Write a review on the article "Dutch East Indies"

Notes

Links

- Indonesia- article from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg. , 1890-1907.

- Ulbe Bosma.// Mainz: , 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Excerpt characterizing the Dutch East Indies

At this time, Petya, to whom no one was paying attention, approached his father and, all red, in a breaking, sometimes rough, sometimes thin voice, said:“Well, now, daddy, I will decisively say - and mummy too, whatever you want - I will decisively say that you will let me into military service, because I can’t ... that’s all ...

The Countess raised her eyes to the sky in horror, clasped her hands and angrily turned to her husband.

- So I agreed! - she said.

But the count immediately recovered from his excitement.

“Well, well,” he said. - Here’s another warrior! Stop the nonsense: you need to study.

- This is not nonsense, daddy. Fedya Obolensky is younger than me and is also coming, and most importantly, I still can’t learn anything now that ... - Petya stopped, blushed until he sweated and said: - when the fatherland is in danger.

- Complete, complete, nonsense...

- But you yourself said that we would sacrifice everything.

“Petya, I’m telling you, shut up,” the count shouted, looking back at his wife, who, turning pale, looked with fixed eyes at her youngest son.

- And I’m telling you. So Pyotr Kirillovich will say...

“I’m telling you, it’s nonsense, the milk hasn’t dried yet, but he wants to go into military service!” Well, well, I’m telling you,” and the count, taking the papers with him, probably to read them again in the office before resting, left the room.

- Pyotr Kirillovich, well, let’s go have a smoke...

Pierre was confused and indecisive. Natasha's unusually bright and animated eyes, constantly looking at him more than affectionately, brought him into this state.

- No, I think I’ll go home...

- It’s like going home, but you wanted to spend the evening with us... And then you rarely came. And this one of mine...” the count said good-naturedly, pointing at Natasha, “she’s only cheerful when she’s with you...”

“Yes, I forgot... I definitely need to go home... Things to do...” Pierre said hastily.

“Well, goodbye,” said the count, completely leaving the room.

- Why are you leaving? Why are you upset? Why?..” Natasha asked Pierre, looking defiantly into his eyes.

“Because I love you! - he wanted to say, but he didn’t say it, he blushed until he cried and lowered his eyes.

- Because it’s better for me to visit you less often... Because... no, I just have business.

- From what? no, tell me,” Natasha began decisively and suddenly fell silent. They both looked at each other in fear and confusion. He tried to grin, but could not: his smile expressed suffering, and he silently kissed her hand and left.

Pierre decided not to visit the Rostovs with himself anymore.

Petya, after receiving a decisive refusal, went to his room and there, locking himself away from everyone, wept bitterly. They did everything as if they had not noticed anything, when he came to tea, silent and gloomy, with tear-stained eyes.

The next day the sovereign arrived. Several of the Rostov courtyards asked to go and see the Tsar. That morning Petya took a long time to get dressed, comb his hair and arrange his collars like the big ones. He frowned in front of the mirror, made gestures, shrugged his shoulders and, finally, without telling anyone, put on his cap and left the house from the back porch, trying not to be noticed. Petya decided to go straight to the place where the sovereign was and directly explain to some chamberlain (it seemed to Petya that the sovereign was always surrounded by chamberlains) that he, Count Rostov, despite his youth, wanted to serve the fatherland, that youth could not be an obstacle for devotion and that he is ready... Petya, while he was getting ready, prepared a lot wonderful words which he will tell the chamberlain.

Petya counted on the success of his presentation to the sovereign precisely because he was a child (Petya even thought how everyone would be surprised at his youth), and at the same time, in the design of his collars, in his hairstyle and in his sedate, slow gait, he wanted to present himself as an old man. But the further he went, the more he was amused by the people coming and going at the Kremlin, the more he forgot to observe the sedateness and slowness characteristic of adult people. Approaching the Kremlin, he already began to take care that he would not be pushed in, and resolutely, with a threatening look, put his elbows out to his sides. But at the Trinity Gate, despite all his determination, people who probably did not know for what patriotic purpose he was going to the Kremlin, pressed him so hard against the wall that he had to submit and stop until the gate with a buzzing sound under the arches the sound of carriages passing by. Near Petya stood a woman with a footman, two merchants and a retired soldier. After standing at the gate for some time, Petya, without waiting for all the carriages to pass, wanted to move on ahead of the others and began to decisively work with his elbows; but the woman standing opposite him, at whom he first pointed his elbows, angrily shouted at him:

- What, barchuk, you are pushing, you see - everyone is standing. Why climb then!

“So everyone will climb in,” said the footman and, also starting to work with his elbows, he squeezed Petya into the stinking corner of the gate.

Petya wiped the sweat that covered his face with his hands and straightened his sweat-soaked collars, which he had arranged so well at home, like the big ones.

Petya felt that he had an unpresentable appearance, and was afraid that if he presented himself like that to the chamberlains, he would not be allowed to see the sovereign. But there was no way to recover and move to another place due to the cramped conditions. One of the passing generals was an acquaintance of the Rostovs. Petya wanted to ask for his help, but thought that it would be contrary to courage. When all the carriages had passed, the crowd surged and carried Petya out to the square, which was completely occupied by people. Not only in the area, but on the slopes, on the roofs, there were people everywhere. As soon as Petya found himself in the square, he clearly heard the sounds of bells and joyful folk talk filling the entire Kremlin.

At one time the square was more spacious, but suddenly all their heads opened, everything rushed forward somewhere else. Petya was squeezed so that he could not breathe, and everyone shouted: “Hurray! Hurray! hurray! Petya stood on tiptoes, pushed, pinched, but could not see anything except the people around him.

There was one common expression of tenderness and delight on all faces. One merchant's wife, standing next to Petya, was sobbing, and tears flowed from her eyes.

- Father, angel, father! – she said, wiping away tears with her finger.

- Hooray! - they shouted from all sides. For a minute the crowd stood in one place; but then she rushed forward again.

Petya, not remembering himself, clenched his teeth and brutally rolled his eyes, rushed forward, working with his elbows and shouting “Hurray!”, as if he was ready to kill himself and everyone at that moment, but exactly the same brutal faces climbed from his sides with the same shouts of “Hurray!”

“So this is what a sovereign is! - thought Petya. “No, I can’t submit a petition to him myself, it’s too bold!” Despite this, he still desperately made his way forward, and from behind the backs of those in front he glimpsed an empty space with a passage covered with red cloth; but at that time the crowd wavered back (in front the police were pushing away those who were advancing too close to the procession; the sovereign was passing from the palace to the Assumption Cathedral), and Petya unexpectedly received such a blow to the side in the ribs and was so crushed that suddenly everything in his eyes became blurred and he lost consciousness. When he came to his senses, some kind of clergyman, with a bun of graying hair back, in a worn blue cassock, probably a sexton, held him under his arm with one hand, and with the other protected him from the pressing crowd.

- The youngster was run over! - said the sexton. - Well, so!.. easier... crushed, crushed!

The Emperor went to the Assumption Cathedral. The crowd smoothed out again, and the sexton led Petya, pale and not breathing, to the Tsar’s cannon. Several people took pity on Petya, and suddenly the whole crowd turned to him, and a stampede began around him. Those who stood closer served him, unbuttoned his frock coat, placed a gun on the dais and reproached someone - those who crushed him.

“You can crush him to death this way.” What is this! To do murder! “Look, cordial, he’s become white as a tablecloth,” said the voices.

Petya soon came to his senses, the color returned to his face, the pain went away, and for this temporary trouble he received a place on the cannon, from which he hoped to see the sovereign who was about to return. Petya no longer thought about submitting a petition. If only he could see him, he would consider himself happy!

During the service in the Assumption Cathedral - a combined prayer service on the occasion of the arrival of the sovereign and a prayer of thanks for the conclusion of peace with the Turks - the crowd spread out; Shouting sellers of kvass, gingerbread, and poppy seeds appeared, which Petya was especially fond of, and ordinary conversations were heard. One merchant's wife showed her torn shawl and said how expensive it was bought; another said that nowadays all silk fabrics have become expensive. The sexton, Petya's savior, was talking with the official about who and who was serving with the Reverend today. The sexton repeated the word soborne several times, which Petya did not understand. Two young tradesmen joked with the courtyard girls gnawing nuts. All these conversations, especially jokes with girls, which had a special attraction for Petya at his age, all these conversations did not interest Petya now; ou sat on his gun dais, still worried at the thought of the sovereign and his love for him. The coincidence of the feeling of pain and fear when he was squeezed with a feeling of delight further strengthened in him the awareness of the importance of this moment.

Plan

Introduction

1 Background

2 General chronology

2.1 Foundation

2.2 Territorial expansion

2.3 Islamic resistance

2.4 Fall of the Dutch East Indies

Bibliography

Introduction

Dutch East Indies (Dutch. Nederlands-Indië; Indon. Hindia-Belanda) - Dutch colonial possessions on the islands of the Malay Archipelago and in the western part of the island of New Guinea. It was formed in 1800 as a result of the nationalization of the Dutch East India Company. Existed until the Japanese occupation in March 1942. Also sometimes called colloquially and informally Netherlandish (or Dutch) India. It should not be confused with the Dutch Indies - Dutch colonial possessions on the Hindustan Peninsula. Like other colonial entities, the Dutch East Indies were created in intense competition both with local state formations and with other colonial powers (Great Britain, Portugal, France, Spain). For a long time it had a predominantly thalassocratic character, representing a series of coastal trading posts and outposts surrounded by the possessions of local Malay sultanates. The conquests of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as well as the use of powerful economic exploitation mechanisms, allowed the Dutch to unite most of the archipelago under the rule of their crown. The Dutch East Indies, with its rich reserves of oil and other minerals, were considered the "jewel in the crown of the Dutch colonial empire."

1. Background

· June 23, 1596: The first Dutch trading expedition, captained by Cornelius Hootman, arrives in Bantam. The Dutch are aware of the potential profitability of these territories. And after their first successful penetration, taking advantage of the gradual weakening of Portugal, they created a number of offices in various cities and provinces of the Netherlands. These offices were associated with the army, navy and large capital and were used for trade with the countries of the East, in particular with this region. Already in 1602 they united into the East India Company, which owned a fairly large share capital for that time.

2. General chronology

· 1602-1800: the company conducts military and trade operations in the Indenesian region. Although the actual territorial gains are insignificant, the Dutch fleet completely controls the interisland waters and main ports, displacing the British and Portuguese.

· 1800-1942: intensive territorial annexation, long and bloody colonial wars with the local population and other European powers.

· 1859: annexation of 2/3 of the territory of Portuguese Indonesia, excluding the East Timor region.

· 1942-1945: Japanese occupation of Indonesia

· 1945-1949: Dutch Restoration, Indonesian War of Independence

· 1969: Annexation of the last Dutch territory, the region of West Papua.

2.1. Base

During the Napoleonic Wars, the territory of Holland itself was captured by France, and all Dutch colonies automatically became French. As a result, the colony was ruled by a French governor-general from 1808 to 1811. In 1811-1816, during the ongoing Napoleonic Wars, the territory of the Dutch East Indies was captured by England, which feared the strengthening of France (by this time Great Britain had also managed to occupy the Cape Colony, the most important trade link between the Netherlands and Indonesia). The power of the Dutch colonial empire was undermined, but England needed a Protestant ally in the fight against the Catholic old colonial powers of France, Spain and Portugal. Therefore, in 1824, the occupied territory was returned to Holland by an Anglo-Dutch agreement in exchange for Dutch colonial possessions in India. In addition, the Malacca Peninsula passed to England. The resulting border between British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies remains to this day the border between Malaysia and Indonesia.

2.2. Territorial expansion

The capital of the Dutch East Indies was Batavia, now Jakarta is the capital of Indonesia. Although the island of Java was controlled by the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch colonial administration for 350 years, from the time of Kun, full control over most of the Dutch East Indies, including the islands of Borneo, Lombok and western New Guinea, was established only at the beginning of the 20th century. .

2.3. Islamic resistance

The indigenous population of Indonesia, supported by the internal stability of Islamic institutions, put up significant resistance to the Dutch East India Company and later to the Dutch colonial administration, which weakened Dutch control and tied up its armed forces. The longest conflicts were the Padri War in Sumatra (1821-1838), the Java War (1825-1830) and the bloody thirty years war in the Sultanate of Aceh (northwestern part of Sumatra), which lasted from 1873 to 1908. In 1846 and 1849 the Dutch made unsuccessful attempts to conquer the island of Bali, which was conquered only in 1906. The natives of West Papua and most of the interior mountainous areas were only subdued in the 1920s. A significant problem for the Dutch was also quite strong piracy (Malay, Chinese, Arab, European) in these waters, which continued until the middle of the 19th century.

In 1904-1909, during the reign of Governor General J.B. Van Hoetz, the power of the Dutch colonial administration extended to the entire territory of the Dutch East Indies, thus laying the foundations of the modern Indonesian state. Southwest Sulawesi was occupied in 1905-1906, Bali in 1906 and western New Guinea in 1920.

2.4. Fall of the Dutch East Indies

On January 10, 1942, Japan, in need of minerals that were rich in the Dutch East Indies (primarily oil), declared war on the Kingdom of the Netherlands. During the Operation in the Dutch East Indies, the territory of the colony was completely captured by Japanese troops by March 1942.

The fall of the Dutch East Indies also meant the end of the Dutch colonial empire. Already on August 17, 1945, after liberation from Japan, the Republic of Indonesia was proclaimed, which Holland recognized in 1949 at the end of the Indonesian War of Independence.

Bibliography:

1. A. Crozet. The Dutch fleet in the Second World War / Trans. from English A. Patients. - M.: ACT, 2005. - ISBN 5-17-026035-0

2. Witton Patrick Indonesia. - Melbourne: Lonely Planet, 2003. - P. 23–25. - ISBN 1-74059-154-2

3. Schwartz A. A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia in the 1990s. - Westview Press, 1994. - P. 3–4. - ISBN 1-86373-635-2

4. Robert Cribb, “Development policy in the early 20th century,” in Jan-Paul Dirkse, Frans Hüsken and Mario Rutten, eds, Development and social welfare: Indonesia's experiences under the New Order (Leiden: Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land - en Volkenkunde, 1993), pp. 225-245.

Literary and historical notes of a young technician

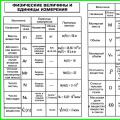

Literary and historical notes of a young technician Collection of basic formulas for a school chemistry course

Collection of basic formulas for a school chemistry course Methods of studying history and modern historical science Classical and modern Russian historical science

Methods of studying history and modern historical science Classical and modern Russian historical science