Information theory of P. Simonov. Simonov, P

The need-information theory of emotions by Pavel Vasilievich Simonov develops the idea of Pyotr Kuzmich Anokhin that the quality of emotion must be considered from the standpoint of the effectiveness of behavior. The entire sensory diversity of emotions comes down to the ability to quickly assess the possibility or impossibility of actively acting, that is, it is indirectly tied to the activating system of the brain. Emotion is presented as a certain force that controls the corresponding program of actions and in which the quality of this program is recorded. From the point of view of this theory, it is assumed that “...an emotion is a reflection by the brain of humans and animals of any current need (its quality and magnitude) and the likelihood (possibility) of its satisfaction, which the brain evaluates on the basis of genetic and previously acquired individual experience”. This statement can be represented as a formula:

E = P × (In - Is),

where E is emotion (its strength, quality and sign); P - strength and quality of current need; (In - Is) - assessment of the likelihood (possibility) of satisfying a given need, based on innate (genetic) and acquired experience; In - information about the means predicted to be necessary to satisfy the existing need; IS - information about the funds a person has at a given moment in time. It is clearly seen from the formula that when Is>In the emotion acquires a positive sign, and when Is<Ин - отрицательный.

K. Izard's theory of differential emotions

The object of study in this theory is private emotions, each of which is considered separately from the others as an independent experiential and motivational process. K. Izard (2000, p. 55) postulates five main theses:

1) the main motivational system of human existence is formed by 10 basic emotions: joy, sadness, anger, disgust, contempt, fear, shame/embarrassment, guilt, surprise, interest;

2) each basic emotion has unique motivational functions and implies a specific form of experience;

3) fundamental emotions are experienced in different ways and have different effects on the cognitive sphere and human behavior;

4) emotional processes interact with drives, with homeostatic, perceptual, cognitive and motor processes and influence them;

5) in turn, drives, homeostatic, perceptual, cognitive and motor processes influence the course of the emotional process.

In his theory, K. Izard defines emotions as a complex process, including neurophysiological, neuromuscular and sensory-experiential aspects, as a result of which he considers emotion as a system. Some emotions, due to underlying innate mechanisms, are organized hierarchically. The sources of emotions are neural and neuromuscular activators (hormones and neurotransmitters, drugs, changes in brain blood temperature and subsequent neurochemical processes), affective activators (pain, sexual desire, fatigue, other emotions) and cognitive activators (evaluation, attribution, memory, anticipation).

Speaking about basic emotions, K. Izard identifies some of their characteristics:

1) basic emotions always have distinct and specific neural substrates;

2) the basic emotion manifests itself through an expressive and specific configuration of muscle movements of the face (facial expressions);

3) the basic emotion is accompanied by a distinct and specific experience, conscious of the person;

4) basic emotions arose as a result of evolutionary biological processes;

5) basic emotion has an organizing and motivating effect on a person and serves his adaptation.

The need-information theory of P. V. Simonov

1964 - Simonov’s newly proposed theory of emotions, which states that emotion is a derivative of the brain and is associated with the satisfaction of needs. That is, emotions are considered as the body’s reaction to information deficiency. Emotions, according to this theory, are divided into negative and positive. Positive ones help reduce the information deficit. The negative ones, on the contrary, mean that this deficit is not eliminated, but rather aggravated and increased. For the first time, it is in Simonov’s theory that emotions acquire a positive character.

This theory can be presented as follows:

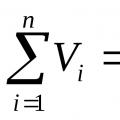

E = fP(In - Is)

Where E is an emotion, P is the quality of an actual need, In is information about the means necessary to satisfy emotions, Is is information about the means available to the subject at the moment.

From this formula it follows that the means of satisfaction, together with the need, lead to the emergence of emotion.

The influence of behavioral stereotypes on the need-motivational sphere of consumers

Consumer behavior is the behavior of the final consumer (individual or household) purchasing a product or service for personal consumption. This is a social activity directly involved in gaining...

The influence of emotions on human life

The information theory of emotions is based on the Pavlovian direction in the study of higher nervous activity of the brain. Pavlov discovered the key mechanism...

NATO information warfare in the Eastern European theater of operations

The Russian-Georgian war included a tough information confrontation in the international arena. According to the vast majority of observers and experts, Russia, having the full support of the population within the country...

The problem of thinking in various theoretical approaches

In the middle of the 20th century, based on successes in the development of ideas from cybernetics, computer science, and high-level algorithmic languages in mathematical programming, it became possible to build a new information theory of thinking...

Psychological readiness of a pregnant woman for motherhood

Filippova G.G. Filippova G. G. Psychology of motherhood. Conceptual model M., 1999; Filippova G. G. Psychology of motherhood and early ontogenesis M., 1999...

Psychological support for the education of patriotism and internationalism in adolescent children

To form patriotism and a culture of interethnic relations, it is necessary not only to know their essence and content, but also those internal psychological and pedagogical components that, taken together, act as bearers of these qualities...

Psychological impact of a computer on a person

Psychology of creativity

A person cannot be considered in a certain context, completely separating him from the rest. An individual is simultaneously a personality, an organism, a representative of a certain nationality, and a bearer of mental functions. Vygotsky notes...

Modern theories of personality

Theories of human activity

Need is the internal state of an organism that needs something. The actualization of the need indicates that the balance, homeostasis between the body and the surrounding world is disturbed. Energy...

Theories of emotions

According to Simonov's theory, a lack of information or an excess of it leads to unsatisfaction of needs and, as a consequence, the appearance of emotions...

Theories of emotions

The domestic physiologist P.V. Simonov tried to present in a brief symbolic form his set of factors influencing the occurrence and nature of emotion. He proposed the following formula for this: E = f [P, (In - Is), .... ], where E is emotion...

Feelings and emotions

Domestic physiologist P.V. Simonov tried to present in a brief symbolic form his set of factors influencing the occurrence and nature of emotion. He proposed the following formula for this: E = F (P (InIs, ...)), where E is emotion...

Emotions

According to psychophysiologist P.V. Simonov, emotion arises when there is a discrepancy between what needs to be known in order to satisfy the need, and what is actually known...

Human emotions and basic approaches to their study in psychology

This type of approach includes the information concept of emotions by psychophysiologist P.V. Simonov. According to his theory, emotional states are determined by a person’s desire or, as Simonov says...

Our approach to the problem of emotions entirely belongs to the Pavlovian direction in the study of higher nervous (mental) activity of the brain.

The information theory of emotions... is neither only “physiological”, nor only “psychological”, much less “cybernetic”. It is inextricably linked with Pavlov’s systematic approach to the study of higher nervous (mental) activity. This means that the theory, if correct, should be equally productive for the analysis of phenomena related to the psychology of emotion, and in the study of the brain mechanisms of emotional reactions in humans and animals.

In Pavlov's writings we find indications of two factors that are inextricably linked with the involvement of the brain mechanisms of emotion. Firstly, these are the inherent needs and drives of the body, which Pavlov identified with innate (unconditioned) reflexes. “Who would separate,” Pavlov wrote, “in the unconditional most complex reflexes (instincts) the physiological somatic from the mental, i.e. from experiencing powerful emotions of hunger, sexual desire, anger, etc.?” However, Pavlov understood that the infinite diversity of the world of human emotions cannot be reduced to a set of innate (even “complex”, even vital) unconditioned reflexes. Moreover, it was Pavlov who discovered the key mechanism due to which the brain apparatus responsible for the formation and implementation of emotions is involved in the process of conditioned reflex activity (behavior) of higher animals and humans.

Based on... experiments, Pavlov came to the conclusion that under the influence of an external stereotype of repeated influences, a stable system of internal nervous processes is formed in the cerebral cortex, and “the formation, the installation of a dynamic stereotype is nervous work of extremely varying intensity, depending, of course, on the complexity of the system of stimuli, on the one hand, and the individuality and state of the animal, on the other.”

“One must think,” said Pavlov from the rostrum of the XIV International Physiological Congress in Rome, “that the nervous processes of the hemispheres in establishing and maintaining a dynamic stereotype are what are usually called feelings in their two main categories - positive and negative, and in their huge gradation of intensities . The processes of establishing a stereotype, completing the installation, supporting the stereotype and violating it are subjectively diverse positive and negative feelings, which has always been visible in the motor reactions of the animal.”

We will often encounter this Pavlovian idea of discrepancy (mismatch - we will say today) between the internal stereotype prepared by the brain and the changed external one in one modification or another in a number of authors who turned to the study of emotions.

Reflective-evaluative function of emotions

Summarizing the results of our own experiments and literature data, we came to 1964. to the conclusion that emotion is a reflection by the brain of humans and animals of any current need (its quality and magnitude) and the likelihood (possibility) of its satisfaction, which the brain evaluates on the basis of genetic and previously acquired individual experience.

In its most general form, the rule for the emergence of emotions can be represented as a structural formula:

E = 1[P,(I„-IWITH),...].

Where E- emotion, its degree, quality and sign; P- the strength and quality of the current need; (ANDn- ANDWith) - assessment of the likelihood (possibility) of satisfying a need based on innate and ontogenetic experience; ANDn- information about the means predictably necessary to meet the need; ANDWith- information on the means available to the subject at the moment.

Of course, emotion also depends on a number of other factors, some of which are well known to us, while we may not yet suspect the existence of others. Well-known ones include:

Individual (typological) characteristics of the subject, primarily individual characteristics of his emotionality, motivational sphere, volitional qualities, etc.; - the time factor, depending on which the emotional reaction takes on the character of a rapidly developing affect or mood that persists for hours, days and weeks; - qualitative features of the need. Thus, emotions that arise on the basis of social and spiritual needs are usually called feelings. A low probability of avoiding an undesirable influence will give rise to anxiety in the subject, and a low probability of achieving the desired goal will give rise to frustration, etc. and so on.

But all these and similar factors determine only variations in the infinite variety of emotions, while the necessary<и достаточными являются два, только два, всегда и только два фактора: потребность и вероятность (возможность) ее удовлетворения.

To avoid misunderstandings... let us dwell on clarifying the concepts we use. We use the term “information” meaning its pragmatic meaning, i.e. change in the probability of achieving a goal (satisfying a need) due to receiving this message.

Thus, we are not talking about information that actualizes the need (for example, about a danger that has arisen), but about information necessary to satisfy the need (for example, about how to avoid this danger). By information we mean a reflection of the entire totality of achieving a goal: the knowledge that the subject has, the perfection of his skills, the energy resources of the body, the time sufficient or insufficient to organize the appropriate actions, etc.

We use the term “need” in its broad Marxian understanding, which is by no means reducible to the mere preservation (survival) of the individual and species. In our opinion, need is the selective dependence of living organisms on environmental factors essential for self-preservation and self-development, the source of activity of living systems, the motivation and purpose of their behavior in the surrounding world. Accordingly, we define behavior as a form of “life activity that can change the likelihood and duration of contact with an external object that can satisfy the body’s need.

A low probability of need satisfaction (I n is greater than I s) leads to the emergence of negative emotions. An increase in the probability of satisfaction compared to the previously available forecast (I c is greater than I n) generates positive emotions.

For example, a positive emotion when eating arises due to the integration of hunger arousal (need) with afferentation from the oral cavity, indicating an increasing likelihood of satisfying this need. In a different state of need, the same afferentation will be emotionally indifferent or generates a feeling of disgust.

So far we have talked about the reflective function of emotions, which coincides with their evaluative function. Please note that price in the most general sense of this concept is always a function of two factors: demand (need) and supply (the ability to satisfy this need). But the category of value and the evaluation function become unnecessary if there is no need for comparison, exchange, i.e. the need to compare values. That is why the function of emotions is not limited to simply signaling influences that are beneficial or harmful to the body, as supporters of the “biological theory of emotions” believe. Let's use the example given by P.K. Anokhin. When a joint is damaged, the feeling of pain limits the motor activity of the limb, promoting reparative processes. In this integral signaling of “harmfulness” P.K. Anokhin saw the adaptive significance of pain. However, a similar role could be played by a mechanism that automatically, without the participation of emotions, inhibits movements harmful to the damaged organ. The feeling of pain turns out to be a more plastic mechanism: when the need for movement becomes very great (for example, when the very existence of the subject is threatened), movement is carried out despite the pain. In other words, emotions act as a kind of “currency of the brain” - a universal measure of values, and not a simple equivalent, functioning according to the principle: harmful - unpleasant, useful - pleasant.

Information theory of emotions P.V. Simonova

The original hypothesis about the reasons for the appearance of emotions was put forward by P.V. Simonov (1966, 1970, 1986). He believes that emotions arise as a result of a lack or excess of information necessary to satisfy a need. The degree of emotional stress is determined according to P.V. Simonov, the strength of the need and the magnitude of the deficit of pragmatic information necessary to achieve the goal. This is presented to him in the form of a “formula of emotions”:

E = - P (In - Is),

where E is emotion; P – need; In – information necessary to satisfy the need; IS – information that the subject has at the time the need arises.

From this formula it follows that emotion arises only when there is a need. There is no need, there is no emotion, since the work

E = 0 (In - Is) also becomes equal to zero. There will be no emotion even if there is a need, and (In - Is) = 0, i.e. if a person has the information necessary to satisfy the need (Is = In). Simonov justifies the importance of the difference (In - Is) by the fact that on its basis a probabilistic forecast of need satisfaction is built. This formula gave Simonov the basis to say that “thanks to emotions, a seemingly paradoxical assessment of the measure of ignorance is provided” (1970, p. 48).

In a normal situation, a person orients his behavior to signals of highly probable events (i.e., to what occurred more often in the past). Thanks to this, his behavior in most cases is adequate and leads to achieving the goal. In conditions of complete certainty, the goal can be achieved without the help of emotions.

However, in unclear situations, when a person does not have accurate information in order to organize his behavior to satisfy a need, a different tactic of responding to signals is needed. Negative emotions, as Simonov writes, arise when there is a lack of information necessary to achieve a goal, which happens most often in life. For example, the emotion of fear and anxiety develops with a lack of information necessary for protection, i.e. with a low probability of avoiding an unwanted influence, and frustration - with a low probability of achieving the desired goal.

Emotions contribute to the search for new information by increasing the sensitivity of analyzers (sense organs), and this, in turn, leads to a response to an expanded range of external signals and improves the retrieval of information from memory. As a result, when solving a problem, unlikely or random associations can be used that would not be considered in a calm state. This increases the chances of achieving the goal. Although responding to an expanded range of signals whose usefulness is not yet known is redundant and irregular, it prevents missing a truly important signal, which, if ignored, could cost one's life.

All these arguments by P.V. Simonov is unlikely to cause serious objections. The point, however, is that he tries to “drive all cases of the emergence of emotions into the Procrustean bed” of his formula and recognizes his theory as the only correct and comprehensive one.

Simonov (1970) considers the advantage of his theory and the “formula of emotions” based on it to be that it “categorically contradicts the view of positive emotions as a satisfied need,” because in the equality E = - P (In - Is) the emotion will be equal zero when the need disappears. From his point of view, a positive emotion will arise only if the received information exceeds the previously existing forecast regarding the probability of achieving the goal - satisfying the need, i.e. when Is will be greater than Jn. Then, for example, an athlete, if this postulate is true, in case of success, i.e. satisfaction of the need to become a winner of a competition or break a record, should not experience any emotions if this success was expected by them. He should only rejoice at success, i.e. when the forecast was worse than it turned out. Otherwise, a person will have neither joy nor triumph if he finds himself at a goal, the achievement of which was certainly not in doubt. And really, why, for example, should an athlete – a master, defeat a beginner – rejoice?

Thus, P.V. Simonov is trying to refute the theory of “drive reduction” of Western psychologists (Hull, 1951, etc.), according to which living systems strive to reduce needs, and the elimination or reduction of needs leads to the emergence of a positive emotional reaction. He also opposes the views of P.K. Anokhin, who essentially adheres to the theory of “reduction” when presenting his “biological” theory of emotions.

According to Anokhin (1976), “a positive emotional state, such as the satisfaction of some need, arises only if the feedback from the results of the action that took place... exactly coincides with the apparatus of the action acceptor.” On the contrary, “the discrepancy between the return afferent messages from the inferior results of the act and the acceptor of the action leads to the emergence of a negative emotion.”

From Simonov’s point of view, satisfying vital needs, eliminating negative emotions, only contributes to the emergence of positive emotions, but does not cause them. If, under the influence of a negative emotion, a person or animal will strive to quickly satisfy the need that determined this emotion, then with a positive emotion everything is much more complicated. Since the elimination of a need inevitably leads to the disappearance of positive emotions, the “hedonic principle” (“the law of maximization”) encourages humans and animals to prevent the absence of a need, to seek conditions for its maintenance and renewal. “The situation is paradoxical from the point of view of the theory of drive reduction,” writes Simonov (1970).

Noting the differences between positive and negative emotions, Simonov points out that the behavior of living beings is aimed at minimizing influences that can cause negative emotions and maximizing positive emotional states. But minimization has a limit in the form of zero, rest, homeostasis, but for maximization, he believes, there is no such limit, because theoretically it represents infinity. This circumstance, Simonov believes, immediately excludes positive emotions from the scope of application of the “drive reduction” theory.

Critical analysis of the theory of P.V. Simonova. The beginning of a serious critical examination of the theory of P.V. Simonov put B.I. Dodonov (1983). True, a significant part of his criticism is directed against the data of P.V. Simonov's derogatory assessments of the merits of psychology in the study of emotions. But still, despite some vehemence in defending the priority of psychology on a number of points, Dodonov also gives constructive criticism. He rightly notes that its author gives the “formula of emotions” a number of divergent interpretations, primarily because he freely uses such concepts as “information”, “forecast”, “probability”, borrowed from cybernetics, which led to distortion understanding their essence and the patterns associated with them.

All these seemingly minor inaccuracies lead people who have a clear understanding of cybernetic terminology to misunderstand what P.V. wants to say. Simonov. It is precisely the ambiguity of Simonov’s interpretation of the “formula of emotions” and the theory itself that allows him, as Dodonov rightly notes, to easily fend off any criticism addressed to him. Dodonov also finds logical inconsistencies in a number of examples cited by Simonov.

Since many aspects of Simonov’s theory remained outside the field of vision of Dodonov, a critical examination of this theory and the “formula of emotions” was given in one of the works (Ilyin, 2000). This criticism is made on two fronts. The first is the theoretical positions of P.V. Simonov, reflected in his “formula of emotions”.

The weaknesses of this position regarding the emergence of emotions, especially positive ones, are visible to the naked eye. The “Formula of Emotions” not only does not have the merit Simonov indicated, but also contradicts common sense and actually observed facts.

First of all, we should dwell on the position that “no need, no emotion.” It is difficult to argue with this, if we keep in mind the initial lack of need. However, the absence of a need and the disappearance of a need when it is satisfied, i.e. achieving a goal - psychologically different situations. This is especially true for social needs. The initial lack of need is one thing, and hence the absence of the process of motivation, the presence of a goal. If they don’t exist, there is no reason for emotion to arise. It’s another matter when, as a result of the existing need and the unfolding motivational process, the goal determined by them is achieved. In this case, pleasure arises from the elimination of a need, not from its absence.

Contrary to Simonov’s statements, people experience joy even with expected success, i.e. when satisfying your needs (desires). Simonov himself notes that “an unsatisfied need is necessary for positive emotions no less than for negative ones” (1981). This means that the main thing in the emergence of emotions is not the lack or excess of information that a person possesses, and not even the presence of a need, but the importance of its satisfaction for the subject.

Thus, in a number of cases, the presence of a social need (the need to do something) and the lack of opportunities for this will not only not cause a negative emotion, but will lead to a positive emotion. Suffice it to remember how happy schoolchildren are when a lesson is disrupted due to a teacher’s illness. And schoolchildren would have reacted completely differently to disrupting a lesson if it was about consultation for an upcoming exam.

A number of ambiguities also arise regarding “excess information”. Why is it needed if Is, equal to In, is sufficient to satisfy the need? Why should a chess player only be happy if he has several options for checkmate? Can't he rejoice in only one way to achieve the goal that he has found?

What is “redundant information”? One that is no longer needed to achieve a goal or make a forecast? And if it is needed for forecasting, then why is it “redundant”? And couldn’t it happen that this “redundancy” (for example, the presence of many equivalent options for achieving a goal) will only prevent the chess player from achieving success, since he will begin to choose the best one and end up in time trouble? As a result, instead of a positive emotion, information excess will cause a negative emotion.

Simonov also writes about this: “Emotions are appropriate only in a situation of information deficiency. After its elimination, emotions can become more of an obstacle to the organization of actions than a factor favorable to their effectiveness” (1970). Therefore, under certain conditions, the advantages of emotions turn dialectically into their disadvantages. From this statement by Simonov it should follow that with excess information, the positive emotions that arise are certainly harmful to the organization of human behavior. What then is their role? It is difficult to understand all these contradictory statements.

In addition, in many cases, a positive emotional background for the upcoming activity (excitement) arises precisely in connection with the uncertainty of the forecast due to the lack or absence of information. On the other hand, an experienced chess player with “super information” finds it boring to play with a beginner. As Simonov writes, “the desire to preserve positive emotions dictates an active search for uncertainty, because completeness of information “kills pleasure”” (1970).

In later work, Simonov (1987), arguing with Dodonov regarding whether emotions are a value, discusses cases in which a person experiences positive emotions from a risk situation. “The subject intentionally creates a deficit of pragmatic information, a low probability of achieving the goal, in order to obtain the maximum increase in probability in the end...” [p. 82]. It is strange, however, that in asserting this, the author does not notice that he is in conflict with his formula of emotions, according to which a positive emotion arises as a result of redundancy of information.

And doesn’t he contradict himself when he writes: “We must fully understand that emotions are only a secondary product of the needs hidden behind them, only indicators of the degree of their satisfaction” (1981). I emphasize that we are not talking about the fact that emotions are indicators of the likelihood of need satisfaction, as the author insists; it is about the degree of its satisfaction. After such statements, is it logical to reject the theory of drive reduction?

Recognizing the presence of complex, bimodal emotions, in which there are both positive and negative experiences of a person (“I am sad and light, my sadness is light...”), Simonov does not further try to explain them from the point of view of the “formula of emotions.” And how to do this, because a person cannot have both a deficit and an excess of pragmatic information at the same time. True, he tries to explain the duality of experiences by the fact that a person immediately actualizes several needs with different probability of their satisfaction, but this is only a general phrase that is not disclosed by the author in any way.

In connection with the ensuing controversy, Simonov writes: “...we emphasize every time that our formula represents a structural model that demonstrates in an extremely brief and clear form the internal organization of emotions” (1981).

But in understanding the formula as a structural model showing the internal organization of emotions, Simonov is again not accurate. On the one hand, he argues that emotions and needs are different phenomena. On the other hand, calling his formula structural, he thereby includes needs (and information too) in the structure of emotion.

Thus, he believes that the main components of emotional reactions are “the strength of the need and the predictive assessment of the effectiveness of actions aimed at satisfying it” (1970). That Simonov’s last statement is not accidental is confirmed by his phrase “transformation of need into emotional arousal” (1970); I emphasize that we are not talking about the appearance of an emotional response (excitement) when a need arises, but about the transformation (transformation, transformation) of the latter into an emotion.

In another of his works, he again repeats that “... the formula clearly reproduces the complex internal structure of emotions, the interdependence of emotions, needs and the likelihood of its satisfaction...” (1987). Although in the same work one can find an exact statement regarding the relationship between emotion, need and probabilistic forecast: “Unlike concepts that operate with the categories of “attitude”, “significance”, “meaning”, etc., the information theory of emotions precisely and unambiguously defines that objectively existing reality, that “standard” that is subjectively reflected in the emotions of humans and higher animals: the need and the likelihood (possibility) of its satisfaction.”

In fact, the relationship between emotion, on the one hand, and need and information, on the other, is not structural, but functional, and therefore the more correct formula is the one that Simonov himself (1970) presented in general form:

E = f(P, ΔI...),

where ΔI = In - Is.

This formula only denotes the dependence of the magnitude of emotions both on the magnitude of the need and on the deficit or excess of information, and nothing more. He himself writes about this quite clearly: “emotion is a reflection by the brain of humans and animals of any actual need (its quality and magnitude) and the likelihood (possibility) of its satisfaction, which the brain evaluates on the basis of genetic, previously acquired individual experience” (1981) . It should be noted that in this case he is talking only about the brain’s reflection of need and probability, and not about the fact that both are structural components of emotion.

From the last formula it no longer necessarily follows that if (In - Is) is equal to zero, then there is no emotion. It can either take place or not. In addition, from the definition of emotion given by Simonov, it follows that the dependence of emotion on need and information indicated by him has only a one-way direction - from cause (need and information) to effect (emotion), but it does not at all follow that between emotions, needs and there are interdependencies in the probability of satisfying the latter, i.e. that P = f(E) or f(In - Is) or that (In - Is) = f(E, P). This is a case where cause and effect cannot change places. Although, contrary to logic, the last two options are also considered by the author.

He believes that, according to the formula, an emotionally excited subject tends to exaggerate the lack of information, i.e. worsen the prognosis, and that an increasing lack of information in many cases (but not all!) suppresses the need and weakens it. This follows from the equality P = E: (In - Is): the greater the deficit, the less the quotient of dividing E: (In - Is) and, accordingly, less P. But with an increase in the deficit of information, it should increase, as states Simonov, and a negative emotion, then the quotient of the division must remain constant. As we see, in this case, too, the “formula of emotions” comes into conflict with the logic developed by its author.

Considering the unidirectionality of the functional dependence of emotions on need and prognosis, the opposite statement that emotions enhance need does not follow from the formula. Which statement is true? If both, then under what conditions and why is this not reflected in the formula or explained in the text?

In general, Simonov’s assertion that emotions increase need is quite risky. After all, if you follow it, not forgetting the “formula of emotions,” then the relationship between them should look like this: the need leads to the appearance of emotion, the emotion strengthens the need, but the stronger the need, the greater the emotion, according to the formula, but the greater the emotion, the the more it increases the need, etc. to infinity. A system with positive feedback would arise, which would certainly lead the nervous system to a breakdown.

It is possible that emotion arises not to enhance a need, but to enhance the activity of the motivational process and drive aimed at satisfying the need. B.I. Dodonov correctly noted that in the “formula of emotions,” based on Simonov’s reasoning, P should be replaced by M (motive).

It should also follow from the formula that the need influences the prediction (assessment) of the probability of achieving the goal. The question is - why? And isn’t it the author himself who claims that the forecast depends on the difference (In – Is), i.e. from information, not needs? The author’s statement that “a huge variety of emotions is characterized by predicting the likelihood of achieving a goal (satisfying a need) at an unconscious level” (1983) also raises doubts.

Criticism of the “formula of emotions” as a tool for measuring the intensity of emotional stress. Initially P.V. Simonov believed that this formula could be both structural, i.e. show what exactly constitutes the basis of emotion, both quantitative, i.e. express the intensity of emotion. The author notes that his formula “is by no means a purely symbolic record of factors, the interaction of which leads to the emergence of emotional tension. The formula reflects the quantitative dependence of the intensity of emotional reactions on the strength of the need and the size of the deficit or increase in information necessary to satisfy it” (1970).

Omitting the inaccuracies made by the author (information cannot satisfy a biological need, it is only used to build a plan to satisfy the need), we note the main thing: with the help of this formula, as Simonov (1970, 1983) believes, it is possible to measure the intensity of emotions (though so far only the most simple). To do this, you only need to measure the magnitude of the need, as well as the necessary and available information. However, this is where both the theoretical and practical weaknesses of the “formula of emotions” become especially obvious.

It is not at all clear how Ying can be determined in each specific case. How do the brain and a person know what Ying should be like - from genetic memory? Most often, a person can only realize that he does not know how to achieve a goal, and not how much information he lacks to achieve it. After all, having knowledge of what you need to have and do to satisfy a need is a special case of human behavior in stereotypical situations. In many cases, a person is forced to make decisions and act in an uncertain environment, without knowing in advance. And without knowing this value, it is impossible to determine the difference between it and Isa.

In addition, for an emotion to receive a negative meaning, it is necessary that the minus sign accompanies not the need (the need itself can be neither negative nor positive, it receives this coloring when the emotion arises), but the difference between In and Is. But this will only happen if (Is - In) is written in the formula. Then, when In > Is, the difference will indeed become negative, like the entire product P(Is - In).

There are other logical and mathematical inconsistencies in this formula. One of them, for example, is Simonov’s statement that a positive emotion will arise even if the difference between In and Is decreases, i.e. if the likelihood of achieving the goal increases. But, according to his own statement and the “formula of emotions”, the closer (In - Is) is to zero, the less negative emotion there will be, and that’s all.

The situation of the appearance of a positive emotion with an increase in the probability of achieving a goal (if the genesis of emotions is considered in dynamics) does not fit into the “formula of emotions” proposed by him, since with any deficiency of information, even if it progressively decreases, the emotion, according to the formula, should still have a negative sign. According to Simonov, it turns out that the less the negative emotion, the greater the positive emotion (we get some compensatory relationships between positive and negative experiences). But he emphasizes the specificity of positive emotions and the mechanisms of its occurrence in comparison with negative emotions. Where is the truth in this case?

P.V. Simonov himself understands the complexity of implementing the ability to measure emotional stress using the formula he proposed. Hence his reservations: “Of course, our formula idealizes and simplifies the real complexity of the phenomena being studied”; “The existence of a linear dependence of emotional stress on the magnitude of the need and the deficit (or increase) of information undoubtedly represents only a special case of actually existing relationships. In addition, here, of course, the time factor, individual (typological) characteristics of the subject and many other, including unknown factors, are involved” (1970; 1983).

But at the same time, Simonov writes: “After all the reservations and clarifications, we will insist that the “formula of emotions” reflects not only logical, but also quantitative relationships between emotion, need and pragmatic information that determines the likelihood of achieving a goal (satisfying a need) "(1970).

A little over ten years later, under the influence of the criticism that fell upon him (Bechtel, 1968; Dodonov 1978; Lomov, 1971; Parygin, 1971; Putlyaeva, 1979; Rappoport, 1968; etc.), which noted that the “formula of emotions” did not is comprehensive and quantitative in the strict sense, Simonov (1981) is forced to write: “Of course, we do not have universal units for measuring needs, emotions and the pragmatic value of information” (1981).

Thus, the “formula of emotions” cannot serve to measure the degree of emotional stress.

It is strange that, while conducting experiments on people that were supposed to support the information theory of emotions, Simonov completely ignored the subjects’ self-reports and trusted more in the changes in GSR and heart rate when the subjects were presented with certain stimuli. But can any change in these indicators necessarily be considered evidence of the occurrence of emotion? After all, they also react to intellectual tension, which is not excluded in Simonov’s experiments.

Trying to prove the unprovable, he gives only those explanations to any facts and draws from them only those conclusions that fit into his “theory”. For example, referring to the data of M.Yu. Kistyakovskaya (1965), he argues that the satisfaction of vital needs (hunger, thirst) leads to peace and drowsiness of the baby, and not to positive emotions. But does the first interfere with the second? And how is it known that when satisfying hunger and thirst, a baby does not develop a positive emotional tone of sensation? Maybe you can find out about this from him?

Many of the “real life” examples cited by Simonov to confirm his theoretical calculations regarding the mechanism of the emergence of emotions, in particular positive ones, do not convince of the correctness of the formula. For example, why, when a person discovers his own delusion, should he laugh at it, as the author writes, “from the height of newly acquired knowledge,” and not be annoyed? Does a chess player who analyzes a lost game and discovers a mistake laugh cheerfully at his mistake? But if this is so, then it will be laughter through tears.

Or another example with pilots experiencing weightlessness for the first time. In the first seconds it seems to them that they are in a catastrophe, but then, since they see that the plane is not falling, they experience an emotion of joy. According to Simonov, this is happening because they received super information that the situation is not dangerous. But where does the presence of pragmatic information (i.e. information on how to escape) and especially super-information come into play, if at that time the pilot was not doing anything and did not plan to do anything, but was simply a passive observer of what was happening to him in a state of weightlessness?

Considering this theory, one cannot help but note Simonov’s sometimes free handling of the basic concepts that reveal his formula, which significantly complicates the understanding of what exactly is being discussed.

There is a lot of uncertainty in the author’s use of such concepts as “pragmatic information” and “pragmatic uncertainty”. In one case, this is “the true volume of upcoming activity” (1970); in the other, it is information about how to satisfy the need, i.e. about the means and ways of achieving the goal.

For him, “deficit or excess of information” suddenly becomes identical to “forecast,” although it is obvious that the forecast is secondary in relation to information. Thus, arguing that positive emotions “arise in a situation of excess pragmatic information (i.e., information about how to satisfy a need) compared to a pre-existing forecast (at a “snapshot”)” (1987), he incorrectly contrasts information with forecast . The information that the subject has at the time of the emergence of a need (IS) is transformed into a hypothesis; he considers achieving the goal (reinforcing the correctness of the forecast) as an increase in the probability of the correctness of the hypothesis, without indicating that this matters for the future (for the present, an increase in the probability of the forecast is already does not matter since the need is satisfied).

The question is significantly complicated by the fact that Simonov does not separate two cases of the emergence of emotions - about the forecast in the process of motivation and about the actual achievement or failure to achieve a goal during actions aimed at satisfying a need. In addition, it should be more clearly indicated in which case we are talking about the emergence of an emotional tone of sensations, and in which – about emotion, since these phenomena are not equivalent. For example, a person has not yet begun to satisfy the need for water, but he is already happy because he has found in the desert an object to satisfy the need - water in a well. Finding an object evokes an emotion. When does a person start drinking, i.e. satisfy the need, then he will have an emotional tone of sensations - pleasure, enjoyment.

So, we can draw the following conclusions. The theory of emotions, called P.V. Simonov "information" explains some special cases of the emergence of emotions in the process of motivation, namely when constructing a probabilistic forecast of need satisfaction. Therefore, it should rather be called “motivational”. To be fair, it should be noted that the “formula of emotions” was supported by a number of authors (Gorfunkel, 1971; Smirnov, 1977; Shingarov, 1970; Shustik and Serzhantov, 1974). D. Price and J. Barrell (Price, Barrell, 1984) even confirmed in one of the experiments with self-esteem the existence of a relationship between emotion, the strength of the need and the likelihood of its satisfaction.

Actually, this does not require special confirmation, since the dependence of emotions on two other factors is obvious. The question is whether the hypothesis and formula proposed by Simonov can explain all cases of the occurrence of emotions, whether this dependence can be considered a general law of human emotions.

This theory ignores emotional reactions that are not associated with the motivational process (for example, those that arise when achieving a goal, i.e., satisfying a need), or emotions that arise without the participation of intellectual activity and comparison of In with Is (for example, fear that occurs instantly and is conscious of us after the fact).

The “formula of emotions” sometimes simply conflicts with reality. It is neither quantitative nor structural; This is a functional formula showing the dependence of the magnitude of emotion on the strength of the need and the presence of pragmatic information used in predicting goal achievement. Explaining the emergence of positive emotions, the author proceeds from the magical power of the formula he invented, and not from actually existing facts. Hence the appearance in his theory of super-information, the practical necessity of which for forecasting he does not justify, but argues according to the principle: it is necessary because the “formula of emotions” requires it.

At the same time, it turns out that positive emotions, based on what Simonov writes, can arise not only with excess information, but also with a simple reduction in the deficit of information, i.e. when the prognosis improves. In general, it seems that when the author forgets about the notorious “formula of emotions,” he expresses reasonable and logically consistent judgments about the causes and role of positive and negative emotions.

This theory is based on the Pavlovian approach to the study of neural networks:

1) The needs and drives inherent in the body are innate reflexes.

2) Under the influence of external repeated influences in the cortex of the b.p. a stable system of internal nervous processes is formed (processes of establishing a “stereotype”, processes of support and violations - a variety of positive and negative emotions).

Emotion– this is the brain’s reflection of any current need and the likelihood of its satisfaction, which the brain evaluates on the basis of genetic and individual experience.

Factors that trigger emotions:

1) Individual characteristics of the subject (motivation, will, etc.).

2) Time factor (affect develops quickly, mood can last a long time).

3) Qualitative features of the need (for example, emotions arising on the basis of social and spiritual needs are feelings).

An emotion depends on a need and the likelihood of its satisfaction. Low probability of need satisfaction→negative emotion, high probability→positive emotion. Example: low probability of avoiding unwanted influence→anxiety arises, low probability of achieving the desired goal→frustration arises

Information- This is a reflection of the totality of means to achieve a goal.

The rule for the emergence of emotions:

Or ![]()

E - emotion, P - strength and quality of need, I n - information about the necessary means to satisfy the need, I s - information about existing means (which the subject has). I n – I s – probability assessment.

I n< И с – положительная эмоция.

And with< И н – отрицательная эмоция.

Later, Simonov rewrote the formula - a strong emotion compensates for the lack of motivation.

Functions of emotions:

1) Reflective-evaluative function. It is the result of the interaction of two factors: demand(needs) and offers(possibility of satisfying this need). But there is not always a need to compare values. Anokhin’s example: the knee joint is damaged → the feeling of pain limits motor function (thereby facilitating recovery). A threat arises → movement is carried out despite pain.

2) Switching function(behavior switches in the direction of improving performance). Approaching need satisfaction → positive emotion → the subject strengthens/repeats (maximizes) the state. Removing need satisfaction→negative emotion→the subject minimizes the state. Assessment of the likelihood of need satisfaction can occur at conscious and unconscious (intuition) levels. When competition of motives arises, a dominant need emerges. Most often, behavior is focused on an easily achievable goal (“a bird in the hand is better than a pie in the sky”).

3) Reinforcing function. Pavlov: reinforcement is the action of a biologically significant stimulus, which gives a signal value to what is combined with it and is biologically insignificant. Reinforcement in the formation of a reflex is not the satisfaction of a need, but the receipt of desirable (emotionally pleasant) or the elimination of unwanted stimuli.

4) Compensatory function. Emotions influence systems that regulate behavior, autonomic functions, etc. When emotional stress occurs, the volume of vegetative shifts (increased heart rate, etc.) usually exceeds the real needs of the body. This is a kind of safety net. designed for situations of cost uncertainty. Apparently, the process of natural selection consolidated the expediency of this excessive mobilization of resources.

The emergence of emotional tension is accompanied by a transition to forms of behavior different from those in a calm state, principles of assessing external signals and responding to them. Those. is happening dominant response. The most important feature of a dominant is the ability to respond with the same reaction to a wide range of external stimuli, including stimuli encountered for the first time in the subject’s life. An increase in emotional stress, on the one hand, expands the range of previously encountered stimuli retrieved from memory, and on the other hand, reduces the criteria for “decision making” when comparing them with these stimuli. Positive emotions: their compensatory function is realized through influencing the need that initiates behavior. In a difficult situation with a low probability of achieving a goal, even a small success (increasing probability) generates a positive emotion of inspiration, which strengthens the need to achieve the goal.

Albert Einstein short biography

Albert Einstein short biography Dalton's law for a mixture of gases: examples of problem solving

Dalton's law for a mixture of gases: examples of problem solving Breathing Boyle-Mariotte's law Boyle-Mariotte's law takes place at constant

Breathing Boyle-Mariotte's law Boyle-Mariotte's law takes place at constant