World literature. Comprehensive preparation for the External Examination

“Aeneid” (“Aeneis”) is an epic by P. Virgil Maron. The epic, dedicated to the fate of the Trojan Aeneas, who was destined to become the founder of the Roman state, was written in the last years of the life of the poet, who died in 19 BC. The composition in 12 songs remained unfinished (in terms of plot, the plan, apparently, was exhausted, and this concerns only the external decoration: some poems are not finished); the poet himself bequeathed not to publish his works that were not published during his lifetime; his executors Varius and Tucca, with the consent of Augustus, violated his will. Virgil's Aeneid, which turned into a national Roman epic and supplanted Ennius's Annals in this regard, became the subject of school study and had a colossal influence on the development of Latin, and later modern European poetry.

Compositionally, the epic is divided into two parts: the first six songs are dedicated to the wanderings of Aeneas before his arrival in Latium, the subsequent ones - to wars with his neighbors. According to the Homeric prototype, the first part is structured compositionally more complex: thus, the content of the second (the destruction of Troy; this is not in Homer, but is in the poems of the Trojan cycle) and the third (the wanderings after sailing from Troy) books chronologically precede the events of the first and are framed as the story of Aeneas himself ( as Odysseus narrates his adventures on the island of the Phaeacians). The fourth canto - one of the brightest and most famous - is entirely independent; The depiction of the love and death of the Carthaginian queen Dido, psychologically deep and rhetorically sophisticated, closer to the technique of the Hellenistic epic (Argonautica by Apollonius of Rhodes) than to the heroic epic of the archaic era, became one of the fundamental texts of European poetry. The fifth song (games in memory of Anchises) goes back to Homer’s descriptions of the games on the island of the Phaeacians (“Odyssey”) and in memory of Patroclus (“Iliad”), the Sixth song (the descent into Hades) corresponds to the eleventh song of the “Odyssey” (a similar plot); Virgil uses it to provide a providential justification for the great destinies of the Roman people, destined to rule the world. From a religious-mythological point of view, it contains many Italic elements, naturally absent from its Greek predecessor.

The second half of Virgil's Aeneid (compositionally emphasized by a special appeal to the Muse, although not at the very beginning of the seventh book) is built more consistently (like its Homeric prototype). One of the most interesting creative reworkings of the motifs of the Iliad is the episode of the death of Nysus and Euryalus in the Italian camp (analogous to the reconnaissance of Diomedes and Odysseus in the 10th song of the Iliad, which ended in the opposite way for them); the description of the shield of Aeneas, also inspired by the Greek epic, serves the purpose of showing the providential nature of the destinies of the Roman power. Here the chronological sequence is not broken; Aeneas’s struggle with Turnus (to whom the poet treats objectively, not wanting to belittle his valor for the sake of Roman patriotism, just as before he did not belittle the virtues of Dido) unfolds to its logical limit: the death of Turnus in single combat (he was killed by Pallant’s belt in the same way as at one time, the armor of Patroclus destroyed Hector). Subsequently, the close connection to many motifs of the Homeric epic served as a reason for accusations of imitation.

The characters are characterized by complexity and depth: Aeneas combines the features of a traditional epic hero with gentleness and piety in the spirit of traditional Roman values (as they were perceived by the generation that lived through the horror civil wars and enthusiastically welcomed the Augustan peace); the character of Dido in his passionate imbalance is distinguished by barbaric traits (like the character of Medea in the previous Greek tradition); the poet does not embellish the protagonist’s submission to divine destinies - and in the underworld, the Carthaginian queen turns away from him indignantly.

The Aeneid is Virgil's most mature work; this affected his techniques, language and style. The influence of Hellenistic poetry, so obvious in the works from " Appendix Virgiliana "(if we recognize their authenticity) and palpable in the "Bucolics", here finally gives way to the fully established classicism of the Augustan era. The chronological sequence of Greek examples is the reverse of the real one: from new poetry (Theocritus in Bucolics) through the didactic epic popular in the Hellenistic era (Hesiod in Dahlias), Virgil turns directly to the ancient Homeric epic. He retains the so-called “divine apparatus,” although the latter, with all the abundance of Italic elements, is more artificial and imbued with philosophical motives(for example, the religious and philosophical skepticism of the prayer of the Numidian king Iarba to his father Jupiter: “If you exist...”). The language and style of the epic were reflected in the maturity of Latin hexametric verse that had been achieved by that time (primarily in the work of the neotericists and, above all, Catullus): the technique of epic hexameter in Virgil, of course, is far from the modernism of Catullus’s circle (he uses archaic forms and words in the spirit of the tradition of the Roman historical epic), but the diversity of Ennius’s language, which reaches the point of bad taste, is alien to him to an even greater extent: in the style of Virgil’s “Aeneid” balanced classicism and strict taste prevail.

The epic contains a wide variety of material, difficult to analyze from the point of view of sources. The sixth canto is a kind of encyclopedia of the kingdom of the dead. Of course, Virgil could not ignore the historical works of Varro - the main source of that time on Roman antiquities - but his colossal erudition was not limited to a few even the largest works. To create the Aeneid, our own research efforts were undertaken, the importance of which is difficult to overestimate.

Virgil's epic "Aeneid" immediately became a classic work, was perceived as second after Homer's and did not lose this significance until modern times. The Roman epic tradition (except for Lucan's Pharsalia) is guided by it. Dante valued him highly; The first verse of Torquato Tasso's "Jerusalem Liberated" testifies to the Christian modification of the Virgilian tradition. Virgil's epic gave two types of imitations: religious epic (Milton's biblical epic with numerous quotations from the Roman poet and Klopstock's "Messiad") and historical ("Lusiad" by Camoes; "Henriad" by Voltaire; on Russian soil - "Rossiad" by Kheraskov). The latest experience is considered unsuccessful, but it rather indicates a loss of taste for the epic. Two songs from the epic by M.V. Lomonosov's "Peter the Great" testify to the dominance of Virgilian solutions in the composition: a sea storm at Solovetsky Monastery in the first and the story of the Streltsy uprisings in the second. At the turn of the XVIII-XIX centuries. the attitude towards Virgil is changing: romantic criticism rearranges its emphasis, and Shakespeare began to be perceived as the “second classic” after Homer, who had lost all influence on the course of the literary process. In Russia V.G. Belinsky supports the opinion that the historical work of Titus Livy was the true Roman epic; The Roman poet no longer has any influential defenders. Scientific criticism makes the following reproach to Virgil: he misunderstood the essence of the epic genre, seeing it in the “divine apparatus,” and created something artificial, which bore artificial fruits in European poetry, which indulged in empty imitation. In the 20th century, the significance of Virgil and his epic began to be assessed more soberly; however, the genre of the heroic epic itself is a thing of the past, and the legacy of the Roman poet has largely lost its relevance.

GENRE ORIGINALITY. The Aeneid was Virgil's "book of life". It was written in the years when peaceful life began in Rome, the state grew stronger, and Octavian Augustus was in the rays of glory. It was at this time that the need for a literary work that would match the political and military greatness of Rome in scale and perfection was felt with particular urgency in society. Virgil accomplished what the Roman poet Quintus Ennius failed to fully achieve. (III V. BC), the author of the poem “Annals”, namely - create a Roman epic. Virgil worked at a different time, when Roman literature had reached maturity. He possessed the literary will and skill, without which such a task would have remained impossible.

Virgil's plan - to glorify Rome, the Romans, Augustus - required a worthy artistic form. Of course, before him there was an indisputable sample- Homer. His the presence is constantly palpable in the Aeneid; We will return to this feature of the poem more than once. "Aeneid", however, was tied up not only with Homer’s poems, but also with the whole complex of legends and myths about the destruction of Troy, about the fate of the heroes who fought at Troy. The mythological element illustrated the idea of the divine origin of Rome.

In the Aeneid, Virgil turned to the legendary past of Rome, to the origins national history, to the founding of a great power. In the poem he mastered extensive scientific and historical material. His scholarship and erudition are palpable in literally every line of the poem.

MYTHOLOGICAL BASIS. The main character, the ancestor of the Romans, appears in the poem Aeneas, one of the participants in the Trojan War. Son of Anchises and Venus herself, he was relative of the Trojan king Priam: both of them led my lineage from Dardanus, son of Zeus. Thus, Aeneas- of divine origin. He arrived at Troy nine years after the start of the war, was an ally of Hector, and together with him attacked the Achaean ships. When the Greeks entered Troy, Aeneas bravely fought his enemies and miraculously escaped death. The gods destined for him that he would become the founder of the Roman state. This motif is also present in folk legends about Aeneas, which have long existed in Italy. Roman poets Naevius and Ennius Aeneas is also mentioned as the founder of Rome and a native of Troy. In addition, the Italian city was considered the ancestor of Rome Alba Longa, whose founder was Ascanius, son of Aeneas, which received the name Yul. He founder legendary the Julian family, to which Julius Caesar belonged, and his relative Octavian Augustus. It is no coincidence that the Princeps treated Virgil’s work on the poem with obvious passion and care: he entrusted the best poet of Italy to create an artistic version of the divine origin of his family.

Mythological characters “coexist” in the poem with real historical figures: while visiting the underworld, Aeneas observes the shadows of many figures of Roman history. Heroes depend on the will of the gods. The latter, as in Homer’s poems, often consult with each other, decide human destinies interfere in people's actions. Predictions, prophetic dreams, ghosts of the dead, etc. play a significant role.

"Aeneid", written in dactylic hexameter, - historical and mythological heroic poem. Virgil adopts many plot, compositional and stylistic techniques of the Homeric epic. And at the same time, the hand of the original master is palpable in the poem.

COMPOSITION. The theme of the poem is set in its first “textbook” lines:

I sing battles and my husband, who was the first from Troy to Italy - a fugitive drawn by Fate - who sailed to the shores of Lavinia.

The Aeneid reveals the fate of Aeneas at the heart of Roman history. The poem consists of 12 books, which form two clearly distinguishable parts. Books 1-6 are the wanderings of Aeneas from the fall of Troy to the landing in Italy. This part is reminiscent of the Odyssey, while Aeneas himself can be compared with the cunning and long-suffering Odysseus. In books 7-12, Aeneas is in Italy, fighting with local tribes: battle scenes predominate here. This part is reminiscent of the Iliad, and the hero is likened to Achilles.

The originality of the Aeneid is that each book of the poem stands out as a separate work, with a beginning and end and an internal plot; at the same time, it is organically “mounted” into the overall whole. Unlike Homer's poems, which flow like a smooth narrative rich in details, the plot of the Aeneid is built like a chain bright episodes, sharply dramatic scenes behind which one can sense a precisely calibrated literary device.

The Wanderings of Aeneas (Books I-VI)

PLOT TWISTS OF THE FIRST PART. Book one, like the Iliad, immediately introduces the reader to the thick of events: before us is Aeneas, who left Troy, sailing to the northern shores of Italy. But the goddess Juno, the hero’s opponent, commands Aeolus, the god of the winds, to create a storm and “scatter” the ships of the “hostile kind.” “Lord of storms and rainclouds,” Aeolus unleashes the fury of the elements on Aeneas’s flotilla. From the very outset of the poem, Virgil shows himself to be a master of depicting highly dramatic scenes and situations. In the future there will be many of them in the poem.

Meanwhile the hurricane roars

It furiously tears the sails and raises the shafts to the stars.

Broken oars; the ship, turning, exposes the waves

Your board; A steep mountain of water rushes after us.

AENEAS IN CARTHAGE. As a result, Aeneas' ships are scattered throughout the sea. But the sea god Neptune, rising from the depths and hearing the noise of the “disturbed sea”, the fury of the winds that did not ask for his will, stops the storm. The rescued ships of Aeneas sail to the African coast, to the country ruled by the young queen Dido, who was expelled by her brother from Phenicia. In Africa, she builds a majestic temple in honor of Juno. Entering the temple, Aeneas is stunned by its lavish decoration and decoration, in particular the wall images of the “Ili-On battles”, portraits of his comrades in Trojan War: Atris (Agamemnon), Priam, Achilles and others. This means that the rumor about the deeds at Troy reached the African shores. Finally Dido appears, “surrounded by a crowd of Tyrian youths.” The queen hospitably welcomes “the fugitives who survived the slaughter of the Danaans.” Touched by the “terrible fate” of Aeneas, Dido throws a luxurious feast in honor of the newcomers. The goddess Venus, the mother of Aeneas, asks Cupid to kindle in Dido a love passion for the hero. She hopes that Aeneas, captured by Dido, will hide from Juno’s wrath. But her plan leads to tragic consequences.

THE STORY OF AENEAS. The content of the second book is Aeneas's story at Dido's feast about his wanderings. Before us is an extensive retrospective, an excursion into the past. This is a compositional device that makes us remember Odysseus at the feast of King Alcinous. Like Homer, Virgil restores the prehistory, taking the reader to the events from the fall of Troy to the appearance of Aeneas with Dido. You command me to experience unspeakable pain again, queen!

I saw with my own eyes how the power of the Trojan power -

A kingdom worthy of tears was crushed by the treachery of the Danaans.

This is the sentiment that opens the story of Aeneas.

THE DEATH OF LAOCOON. The tenth year of the siege of Troy is coming to an end. But it is possible to take it only thanks to cunning. The Greek Sinon runs over to the Trojan camp and lulls the vigilance of the besieged with lies. He sets out a version according to which the Greeks allegedly intended to sacrifice him, but he miraculously managed to escape. The Greeks, with the help of Athena, built a huge wooden horse, which they placed near the walls of Troy. Sinon assures the Trojans that the horse does not pose any danger, and therefore it can be brought inside the fortress. Meanwhile, armed Achaean warriors hid in the belly of the horse. The Trojans break open the wall and bring a wooden horse into the city. However, the priest Laocoon warns them:

You are all crazy! Do you believe that the gifts of the Danaans can be without deception?

Another translation: “Fear the Danaans who bring gifts.” This expression has become proverbial. This is how the death of Laoko-on is described:

Suddenly, across the surface of the sea, bending their body in rings, Two huge snakes (and it’s scary to talk about it) swim towards us from Tenedos and strive for the shore together: Bodies top part rose above the swells, a bloody Crest sticks out of the water, and a huge tail drags, exploding the moisture and writhing in a wavy movement. The salty expanse groans; snakes crawled onto the shore. The burning eyes of the reptiles are full of blood and fire, The trembling tongue licks the whistling, terrible mouths. We ran away without any blood on our faces. The snakes are crawling straight towards Laocoon and his two sons, having first squeezed in a terrible embrace, entwined the thin limbs, tormented the poor flesh, ulcerated, torn with their teeth; The father rushes to their aid, shaking his spear. The reptiles grab him and tie him in huge rings, wrapping themselves twice around his body and twice around his throat, and towering over his head with a scaly neck. He strives to break the living bonds with his hands, Poison and black blood pours into the priest's bandages, A shuddering scream reaches to the stars

The unfortunate one rises...

These are the details of the death of Laocoon and his sons that are imprinted in our memory. They are strangled by snakes. But the simple-minded Trojans see this as the gods’ revenge on the priest, a deceitful predictor who wanted to deprive them of their prey - a wooden horse.

The tragic death of Laocoon has become a theme in world art. The masterpiece of Hellenistic sculpture is the “Group of Laocoon”, created by three masters: Agesander, Athenodorus and Polydorus. It is kept in the Vatican Museum. This work played a huge role in the formation of classicism in the fine arts; it is analyzed in detail by the outstanding German writer and esthetician G.E. Lessing in his treatise “Laocoon” (1766), one of the fundamental documents of world aesthetic thought. The plot of Laocoön was used in his painting by the great Spanish painter El Greco.

AENEAS IN THE BURNING THREE. So, having celebrated the capture of the booty - a wooden horse, the Trojans, without thinking about the danger, go to sleep. At night, the shadow of Hector appears to Aeneas, who conjures the hero: “Son of the goddess, run, save yourself from the fire quickly! The enemy has taken possession of the walls, Troy is falling from the top!” It turns out that the Greeks disembarked, while others outside Troy only imitated sailing away from the besieged city. Now they have taken possession of his strongholds. The battle breaks out, the city is on fire, houses are destroyed. The Achaeans mercilessly exterminate the defenders of Troy.

One of the most poignant scenes of the second book is the death of Priam. The elder “dresses his decrepit body in armor, puts on a useless sword.” Pyrrhus kills Priam at the altar, plunging his sword into him “to the hilt.” Queen Cassandra is captured. Aeneas’s mother Venus appears to her son, fighting on the streets of Troy, with the words: “Run away, my son, leave the battle! I will always be with you and will bring you safely to your father’s door.” With the help of the goddess, Aeneas manages to take his loved ones,

snatching them from the fire: the elder father Anchises, the wife Creus, the daughter of Priam and Hecuba, the son of Ascanius, a lovely child. Having placed his father on his shoulders, Aeneas makes his way through the fire-torn city to the exit, to the Scaean Gate. At this moment Creusa disappears. Aeneas searches for her in vain. The ghost of Creusa appears, asking Aeneas not to indulge in “insane grief.” Everything happened by the will of the immortal ruler of Olympus. Aeneas awaits in the future a “happy destiny”, and a “kingdom”, and a “royal spouse”.

Aeneas manages to leave the city: his father and son remain with him. The hero is joined by the surviving Trojans, who, together with Aeneas, are hiding on a wooded mountain. Aeneas builds ships and sails with his companions at random.

THE ADVENTURES OF ANEAS. The third book of the poem- This is a continuation of the story of Aeneas, covering six years of his wanderings. The story is built in the form of a chain of colorful episodes, reminiscent of those O which Odysseus told to King Alcinous. Like Homer, Virgil has an element of the miraculous here. During a stop in Thrace, he hears the voice of Polydorus, who was killed by the Thracian king who seized his gold, coming from underground. This forces Aeneas to quickly move away from the “criminal land.” Then the wanderers visit Crete, but a plague rages on the island. On the island of Strofada they meet terrible harpies. Having stopped for the winter at Cape Actium (the same place where Octavian won his memorable victory over Antony), Aeneas and his companions organize games in honor of Apollo. Finally they arrive in Epirus, where the soothsayer Helen, one of the sons of Priam, who became the husband of Andromache, Hector’s widow, predicts to the hero of the poem that he will rule Latium in Italy.

God only reveals this to you through my lips.

Let's hit the road! And raise the great Troy to heaven with your deeds!

This is how Gelen admonishes Aeneas. The latter successfully avoids Scylla and Charybdis, as well as the Cyclopes, led by the “sightless” Polyphemus - textbook figures, memorable from the Odyssey. He meets Aeneas and Achaemenides, born in Ithaca, the unfortunate companion of Ulysses (Odysseus), whom the latter, miraculously escaping Polyphemus, forgot in his cave. Anchises dies in Sicily: “the best father left his tired son.” With this episode, Aeneas completes his story. What happened next was reported in the first part: a storm that broke out drove Aeneas’s ships to the African coast, to Carthage.

LOVE OF AENEA AND DISO. In the eventful Aeneid there are episodes and scenes key, textbook ones that are literally etched in the reader’s memory. This is love story of Aeneas and Dido, unfolding in the fourth book of the poem, one of the most impressive.

Virgil writes about love in a new way, compared to Homer: it is a passion that torments and subjugates a person. Dido is a victim of the feeling instilled in her by Cupid.

Evil care meanwhile ulcerates the queen and torments

The wound, and the secret fire, spreading through the veins, consumes.

The queen wants to remain faithful to the memory of her deceased husband, but is already powerless to resist the attraction. Dido confesses to her faithful friend:

An unusual guest arrived in our city unexpectedly yesterday! How beautiful he is in face, how powerful and brave in heart! I believe, and I believe for good reason, that he was born of immortal blood. Those who are low in soul are exposed to cowardice. He was driven by a terrible fate, and he went through terrible battles...

Note: Aeneas amazed Dido with his courage. (Remember, in Shakespeare Othello says about Desdemona: “She loved me for my torments, and I loved her for my compassion for them.”)

This time, the two goddesses, Juno and Venus, are not competing with each other, but join forces to ensure the happiness of two people. Each of them has their own interests. Juno does not want Aeneas to arrive in Italy, and powerful Rome to become a mortal threat to Carthage. Venus wants to save her son from new disasters. Juno proposes to unite the heroes in marriage. During the hunt of Aeneas and Dido, Juno creates a storm, the heroes hide together in a cave for the night and here they unite. Few people in ancient literature depicted love, like a disastrous passion, with such force as Virgil:

The first cause of troubles and the first step towards death Was this day. Having forgotten about rumors, about a good name, Dido no longer wants to think about secret love: She calls her union marriage and covers up her guilt with words.

He was received by Dido and honored with her bed; Now they spend the long winter in debauchery, having forgotten their kingdoms in captivity of shameful passion.

But the idyll of love is short-lived. Virgil puts the hero in front of a painful moral dilemma: love or duty. The gods, and above all Jupiter, remind Aeneas that he is a “slave of women”, has forgotten about the “kingdom and great exploits”, that for his son he must “obtain the kingdom of Italy and the lands of Rome.” Aeneas, this true Roman hero, submitted to the will of the gods. He has no thoughts of contradicting them. And the unfortunate Dido quickly realizes that separation from her lover is imminent. This plunges the queen into despair. She reproaches Aeneas for “treachery.” And at the same time he conjures with the “bed of love”, the “unfinished wedding song”: “Stay!” The hero, “obedient to Jupiter’s will,” only reminds that he is not “the master of his own life,” and therefore sails to Italy as directed from above. And this only aggravates the torment of the queen, wounded by the hard-heartedness of Aeneas, who refused her love. With undoubted psychological authenticity, Virgil reveals the mental state of Dido, a heroic and tragic figure at the same time. Worthy to compete with Euripides' Medea and Phaedra. She is either full of moral dignity or broken by grief. Love gives way to anger, the queen predicts a cruel enmity between the Carthaginians and Rome, the birth of the coming avenger, Hannibal.

Events are moving inexorably towards a terrible denouement. As Aeneas's ships sail from the African shores, Queen Dido mounts a huge funeral pyre and unsheathes the blade once given to her by her lover:

“Even though I die unavenged, I will die a desired death, Let the cruel Dardanian look at the fire from the sea, Let my death be an ominous sign for him!” As soon as she said this, the maids suddenly saw how she drooped from the mortal blow, her hands and sword stained with blood. A Scream flew through the high chambers, and, in a frenzy, the rumor rushed through the troubled city. The palace was immediately filled with the lamentations, moans and cries of Women, and the ether echoed with a piercing, sorrowful cry.

We find a somewhat similar plot motif in the Odyssey. There, the main character, at the behest of the gods, must leave the arms of the nymph Calypso, with whom he spent seven years. Odysseus leaves the nymph for his home, his native land, Penelope, to which he is heading. Calypso regretfully breaks up with him, complaining that the gods were jealous of their happiness. However, their breakup is not tragic, like that of Aeneas and Dido.

LOVE AND DUTY. In Virgil's poem, the hero obeys not just the will of Jupiter, but fulfills the highest national duty. At first glance, Virgil poeticizes the official Augustan policy with the story of Aeneas and Dido. Aeneas, as an ideal Roman, as a citizen, sacrifices the personal in the name of the highest state interests. But the logic of artistic images and situations tells a different story. Dido, whose feeling and life itself ruthlessly sacrificed to higher goals, evokes the reader's compassion. And he has one of the “eternal questions” that people have faced throughout their centuries-old history: isn’t human life, the one and only, the highest value? Is it, after all, a state for a person, and not vice versa?! So literature, so distant from us in time, if it does not solve, then puts forward problems that are invariably relevant! The hero of the poem will not be left by the painful thought of Dido. And later, seeing her in the underworld with a wound in her chest, he admits with regret: “I did not leave your shore, queen, of my own free will!” But Dido, “hard as flint,” remains silent and then disappears. Her silence is more significant than words.

AENEAS IN SICILY. After the dramatic intensity of the fourth book, the atmosphere fifth- more calm. Having left Carthage, Aeneas and his friends stop in Sicily. There he organizes memorial games in memory of his father Anchises, on the first anniversary of his death. Funeral games were a tradition among the Greeks; the 23rd song of the Iliad describes the same games in honor of Patroclus, a friend of Achilles, who fell at the hands of Hector. In honor of Hector himself, a funeral feast is held in Troy. This tradition was revived in Rome primarily through the efforts of Augustus, who sought, on the one hand, to instill respect for antiquity, and on the other, to encourage young people to take part in sports competitions. Virgil depicts competitions in rowing, running, shooting, and equestrian sports. After this, Aeneas reaches the shores of Italy on his ships.

AENEAS IN THE KINGDOM OF THE DEAD. Significant and sixth book poems. Near the city of Cuma, not far from Vesuvius, on the slope of a mountain there is a cave, which is the entrance to the kingdom of the dead. There Aeneas in the temple of Apollo is met by the prophetess Sibyl, the “prophetic maiden”, whom the hero asks to tell about his future fate. “You, who are now freed from the terrible dangers at sea! More dangers await you on land,” says the Sibyl. Together with her, Aeneas, equipped with a magical golden branch, descends into the afterlife, described by the poet with great detail. This motif was already present in Homer (in the 11th song of the Odyssey, where the hero visits the kingdom of the dead, talks with the shadow of his mother, with his fighting friends - Agamemnon, Achilles); it will be developed further, primarily in Dante's Divine Comedy.

On Aeneas's path there are various monsters. Charon transports him across the Acheron River, he puts the dog Kerber to sleep. In Tartarus, mythological characters, sinners, rebels, and atheists experience torment. The central episode is a meeting with the shadow of Father Anchises, a righteous man in paradise. Happy with the arrival of his son, he utters words that are poignant in their authenticity.

So you came after all? Have you overcome an impossible path? Is your holy loyalty? I didn't expect anything else from you.

PROPHECY ABOUT THE GREATNESS OF ROME. Virgil puts into the mouth of Anchises a prophecy about the future of Rome, about “the glory that will henceforth accompany the Dardanids,” and shows his son “the souls of great men.” He makes a kind of historical excursion from the distant past to Virgil’s contemporary reality. And among these “great men” he names Anchises and Octavian, whose reign will mark the power of Rome. The advent of the "golden age".

Here he is, the man about whom you were told so often: Augustus Caesar, nourished by the divine father, will again return the golden age to the Latin arable lands.

Among the great men - Roman king Tarquinius; patrician families Decii And Druze, who gave many wonderful commanders; Torquatus, conqueror of the Gauls, those who attacked Rome; Gracchi, tribunes of the people; legendary tyrant fighter Lucius Brutus (not to be confused with his descendant Marcus Brutus, Caesar's killer). Anchises speaks - and Virgil himself speaks through his lips - about the historical mission of the Romans. Inferior to the Hellenes in fine arts and scientific achievements, the Romans are called upon to be rulers of the world.

Others will be able to create living sculptures from bronze. Or it’s better to repeat the faces of husbands in marble, It’s better to conduct litigation and the movements of the sky more skillfully Calculate or name the rising stars - I don’t argue. Roman! You learn to rule peoples in a sovereign way - This is your art! - to impose conditions of peace, to show mercy to the submissive and to humble the arrogant through war!

Aeneas in Italy (quiches VII-XII)

In the second part of the poem, the hero’s wanderings are replaced by military episodes, in which he is “involved” already in Italy. Virgil outlines a new turn in the narrative:

I start to sing

I'm talking about war, about kings driven to death by anger,

And about the Tyrrhenian fighters.

Virgil was given time to work - 12 years, but never completed it. He bequeathed this poem to burn to his friend. Not a word about Augustus - but he did not destroy it. He approved of the political trends that the Romans are the chosen people, destined to rule the world.

Consists of 12 books. Virgil divides it into two parts.

The first part - Aeneas's flight from burning Troy and arrival in Carthage - 5 books.

The second part is a story about the wars in Italy. In the middle of the sixth book is a story about Aeneas’s descent into the kingdom of the dead. Aeneas comes down to find out where he is sailing and about the future fate of Rome. “You suffered at sea, you will suffer on land,” the Sibyl tells Aeneas, “is waiting for you.” new war, a new Achilles and a new marriage - with a foreigner; You, in spite of adversity, do not give up and march more boldly!”

They arrive at the mouth of the Tiber, Latium region. Travelers dine by placing vegetables on flat cakes. We ate vegetables, ate flatbread. “There are no tables left!” - jokes Yul, son of Aeneas. “We are at the goal! - Aeneas exclaims. - The prophecy has come true: “you will chew your own tables.” We didn’t know where we were sailing, but now we know where we were sailing.”

But the goddess Juno is furious - her enemy, the Trojans, has prevailed over her power and is about to erect a new Troy: “Be it war, be there common blood between father-in-law and son-in-law!” There is a temple in Latium; when peace, its doors are locked, when war, its doors are open; With a push of his own hand, Juno opens the iron doors of war. ...

Aeneas's mother, Venus, goes to the forge of her husband Vulcan (Hephaestus) so that he forges armor for her son, as he once did for Achilles. On the shield of Achilles the whole world was depicted, on the shield of Aeneas - the whole of Rome: the she-wolf with Romulus and Remus, the abduction of the Sabine women, the victory over the Gauls, the criminal Catiline, the valiant Cato and, finally, the triumph of Augustus over Anthony and Cleopatra. ...

After the first day of struggle - Altars are erected, sacrifices are made, oaths are pronounced, two formations of troops stand on two sides of the field. And again, as in the Iliad, the truce suddenly breaks down. A sign appears in the sky: an eagle swoops down on a flock of swan, snatches the prey, but the flock falls on the eagle, forces it to abandon the swan and puts it to flight. “This is our victory over the alien!” - shouts the Latin fortuneteller and throws his spear into the Trojan formation. The troops rush at each other, and a general battle begins.

Aeneas and Turnus found each other: “they collided, shield with shield, and the ether was filled with thunder.” Jupiter stands in the sky and holds the scales with the lots of heroes.” Turnus is wounded and asks not to kill him, but Aeneas sees the belt of his murdered friend on him and does not spare Turnus. (Duel between Aeneas and Turnus = Achilles and Hector)

Virgil seemed to combine the Iliad and the Odyssey in reverse order. Virgil does not hide the fact that he used Homer as an example.

Aeneas is destined to found the Roman state, which will own the world. The poem is directed to the future. Another super task associated with the hero. About the fate of Aeneas, about the fate of Rome - fate is the main force that controls everything. Homer's heroes were not blind toys, but here there is complete submission to fate, denial of personality. It is aimed at the future, so it contains a lot of verbs. Selection of parts.

The ideological content was influenced by the Stoics. Suffering is justified by a goal, harmony. The reason for human suffering is that people are not always reasonable. Gods are needed to show the hierarchy of knowledge and subordination. Only the gods know the truth. Outwardly, the poem resembles Homer. But the world of the Greeks is familiar to us, but in Virgil the world expands to extraordinary limits. The concept of time expands. The hero is interested in the future of his descendants. The poem is not finished. It already seemed to many of Augustus’ contemporaries that their hopes were not justified. Virgil leaves the hero at a crossroads, the murder of Turnus.

Peculiarities:

Dedicated to both the past and the present

Unlike “I” and “O” - Homer does not know what will happen next, it does not interest him. V. knows what will happen next (3 Punic warriors, Carthage destroyed).

Dramatic, and G. has a calm narrative tone

Correlates the mythological past and modernity

Fate, rock is the main force that controls events. The gods are sublime and wise, the main thing is not them, but fate.

Aeneas is like an ideal Roman, but there is the tragedy of a man who must submit to fate.

Both Aeneas and Dido are shown in development

Each episode is epilia.

Virgil gained worldwide fame especially with his third great work - the heroic poem "Aeneid". As the very name of this work shows, here we find a poem dedicated to Aeneas. Aeneas was the son of Anchises and Venus, and Anchises was cousin Trojan king Priam. In the Iliad, Aeneas appears many times as the most prominent Trojan leader, the first after Hector. Already there he enjoyed the constant favor of the gods, and the Iliad (XX, 306 et seq.) speaks of the subsequent reign of him and his descendants over the Trojans. In the Aeneid, Virgil depicts the arrival of Aeneas and his companions in Italy after the fall of Troy for the subsequent founding of the Roman state. All this mythology, however, is not given in full in the Aeneid, since the founding of Rome is assigned to the future and only prophecies are given about it. The twelve songs of the poem created by Virgil bear traces of incomplete work (. There are a number of contradictions in content. Virgil did not want to publish his poem in this form and before his death he ordered it to be burned. But by order of Augustus, the initiator of this poem, it nevertheless, it was published after the death of its author.

a) The plot of the poem consists of two parts: the first six songs of the poem are dedicated to the wanderings of Aeneas from Troy to Italy, and the second six are dedicated to the wars in Italy with local tribes. Virgil imitated Homer in many ways, so that the first half of the Aeneid can well be called an imitation of the Odyssey, while the second half of the Iliad.

Song I, after a short introduction, tells about the pursuit of Aeneas by Juno and about a sea storm, as a result of which he and his companions arrive in Carthage, that is, in North Africa. Venus asks Jupiter to help Aeneas establish himself in Italy, and he promises her this. In Carthage, Aeneas is encouraged by Venus herself, who appears to him in the form of a huntress. Mercury prompts the Carthaginians to kindly accept Aeneas. Aeneas appears before Dido, the queen of Carthage, and she arranges a solemn feast in honor of the arrivals.

Canto II is dedicated to Aeneas's stories at Dido's feast about the destruction of Troy. Aeneas tells in detail about the treachery of the Greeks, who could not take Troy for 10 years and eventually resorted to an unprecedented trick with a wooden horse. Troy was burned by Greek soldiers who emerged at night from the inside of a wooden horse (1 -199). The song is replete with many dramatic episodes. Laocoon, a priest of Neptune in Troy, who objected to the admission of a wooden horse into the city and himself threw a spear at it, died along with his two sons from the bite of two snakes that came out of the sea (199-233). The recently deceased Hector appears to Aeneas in a dream and asks him to resist his enemies. And only when the royal palace was already burning and Pyrrhus, the son of Achilles, brutally killed the defenseless elder Priam, king of Troy, near the altar in the palace, Aeneas stopped fighting, and even then after the admonition of Venus and after a special miraculous sign. Together with his penates and companions, along with his wife Creusa and son Ascanius (Creusa immediately disappears), carrying his elderly father Anchises on his back, Aeneas finally gets out of the burning city and hides on the neighboring Mount Ida.

Canto III is a continuation of Aeneas' story about his journey. Aeneas ends up in Thrace, Delos, Crete, and the Strophadian Islands; but under the influence of various frightening events, he cannot find refuge for himself anywhere. Only at Cape Actium were games held in honor of Apollo, and only in Epirus was he touchingly greeted by Andromache, who married Helen, another son of Priam. Various circumstances prevent Aeneas from establishing himself in Italy, although he safely passes Scylla and Charybdis, as well as the Cyclops. Anchises dies in Sicily.

Canto IV is dedicated to the famous romance between Dido and Aeneas. Dido, admiring the exploits of Aeneas, seeks to marry him, in which Juno helps her. Aeneas faces a great future in Italy, where the gods themselves are sending him, and he cannot stay with Dido. When Aeneas's fleet sails from the coast of Africa, Dido, cursing Aeneas and foreshadowing future wars between Rome and Carthage, throws herself into a blazing fire and pierces herself with the sword that Aeneas gave her.

In canto V, Aeneas arrives in Sicily for the second time, where he organizes games in honor of the deceased Anchises. However, Juno does not stop her intrigues against Aeneas and, through Iris, encourages the Trojan women to set fire to his fleet; Through Aeneas' prayer to Jupiter, this fire stops. Having founded the city of Segesta in Sicily, Aeneas headed to Italy.

Canto VI depicts the arrival of Aeneas in Italy, his meeting with the prophetess Sibyl in the temple of Apollo at Cumae and receiving from her advice for descending to the underworld to learn there from Anchises a prophecy about his future (1-263). Guided by the Sibyl, Aeneas descends into the underworld, which is depicted in Virgil in great detail. They are met first by various monsters, then by Charon, the terrible ferryman across the Acheron River, then they have to put Kerberos to sleep and meet an innumerable number of shadows, and, among other things, the shadows of well-known dead. In Tartarus, in the very deep place the underworld, famous mythological sinners such as the daring Titans, the rebels Aload, the atheist Salmoneus, the dissolute insolent Titius and Ixion and others experience eternal torment. Passing the palace of Pluto, Aeneas and the Sibyl find themselves in Elysium, that is, in the region where the righteous spend their lives blissfully and where Aeneas meets Anchises, showing all his future descendants and giving advice regarding the wars in Italy. After this, Aeneas returns to the surface of the earth.

The second part of the Aeneid depicts Aeneas' wars in Italy for his establishment there for the sake of founding the future Roman state.

In Canto VII, Aeneas, having entered Latium, receives the consent of the king of this country, Latinus, to marry his daughter Lavinia. However, Juno, the constant opponent of Aeneas, upsets this marriage and raises another Italic tribe, the Rutuli, with their leader Turk, against Latinus. Latinus leaves power, and due to the machinations of Juno, a break occurs between Aeneas and the inhabitants of Latium, to whose side 14 other Italic tribes go over.

In canto VIII, Turnus enters into an alliance with Diomedes, the Greek king in Italy, and Aeneas with Evander, a Greek from Arcadia, who founded the city that was destined to become Rome. Evander's son Pallant, together with Aeneas, asks for help from the Etruscans, who rebelled against their king Mecenzius. At the request of Venus, her husband Vulcan makes for Aeneas brilliant weapons and a shield of highly artistic work with paintings of the future history of Rome.

Canto IX - description of the war. The Rutuli, under the leadership of Turnus, break into the Trojan camp to burn the ships, but Jupiter turns these ships into sea nymphs. A very important episode is with two Trojan warriors - friends Nisus and Euryalus, who bravely defend the entrance to the Trojan camp, but die after reconnaissance undertaken by them in the Rutul camp. After this, Turnus again breaks into the Trojan camp and after fierce battle returns home unharmed (176-502).

In Song X there is a new fierce battle between enemies, this time with the participation of Aeneas, who until that time was with the Etruscans. Even Jupiter is unable to stop the fight. Turnus resists Aeneas landing on shore and kills Pallant. Turnus is protected by his patroness Juno. But Aeneas kills Mezentius and his son.

In canto XI - the burial of the killed Trojans, the meeting and quarrel between Latinus and Turnus. As a result, the warlike Turnus prevails over Latinus, who proposed a truce with the Trojans. Next is the performance of the Amazon Camilla on the side of the Rutuli, which ends with her death and the retreat of the Rutuli (445-915).

Canto XII is mainly devoted to the single combat of Aeneas and Turnus, which is depicted in solemn tones, with various slowdowns and retreats. Juno stops pursuing Aeneas, and Turnus dies at the hands of the latter.

The Aeneid was not completed by Virgil; it does not depict the events that followed the war of the Trojans and Rutuli: the reconciliation and unification of the Latins with the Trojans, where the history of Rome began; the marriage of Aeneas to Lavinia; the appearance of their son Iul (who, according to other sources, was identified with the former son of Aeneas, Ascanius); the appearance in the descendants of Iul of the brothers Romulus and Remus, from whom came the first Roman kings.

b) The historical basis for the appearance of the Aeneid was the enormous growth of the Roman Republic and subsequently the Roman Empire, a growth that imperatively required both historical and ideological justification. But historical facts alone are not enough in such cases. Here mythology always comes to the rescue, the role of which is to turn an ordinary story into a miracle. Such a mythological basis for the entire Roman history was the concept that Virgil used in his poem. He was not its inventor, but only a kind of reformer, and most importantly, its most talented exponent. The motive for Aeneas's arrival in Italy is found in the Greek lyricist of the 6th century. BC. Stesichora. The Greek historians Hellanicus (5th century), Timaeus (3rd century) and Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1st century BC) developed a whole legend about the connection between Rome and the Trojan settlers who arrived in Italy with Aeneas. Roman epic writers and historians also did not lag behind the Greeks in this regard, and almost each of them paid one or another tribute to this legend (Nevius, Ennius, Cato the Elder, Varro, Titus Livy). It turned out that the Roman state was founded by representatives of one of the most respectable peoples of antiquity, namely the Trojans, that is, the Phrygians; at the same time, Augustus, as adopted by Julius Caesar, ascended to Iulus, the son of Aeneas. And regarding Aeneas, all ancient world there was never any doubt that he was the son of Anchises and Venus herself. This is how Rome justified its power. And mythology came in handy here, since the impression of a grandiose world empire suppressed minds and did not want to put up with the low and, so to speak, “provincial” origin of Rome.

From here follows the entire ideological meaning of the Aeneid. Virgil wanted to glorify the empire of Augustus in the most solemn form; and Augustus actually emerges from him as the heir of the ancient Roman kings and has Venus as his ancestor. In the Aeneid (VI), Anchises shows Aeneas, who came to him in the underworld, all the glorious descendants who will rule Rome, kings and social and political figures. And he ends his speech with elephants, in which he contrasts Greek art and science purely Roman art - military, political and legal (847-854):

Let the revived coppers forge finer than others,

I still believe that they will remove the living faces from the marble,

They will speak more beautifully in the courts, the movements of the sky

The rising stars will be determined by a compass.

You rule the people with authority, Roman, remember!

Behold, your arts will be: to impose the conditions of peace,

Spare the overthrown and overthrow the proud! (Bryusov.)

These words, like many other things in Virgil, indicate that the Aeneid is not just praise for Augustus and a justification for his empire, but also a patriotic and deeply national work. Of course, there is no patriotism without any socio-political ideology; and this ideology in this case is the glorification of the Augustan empire. Nevertheless, this glorification is given in the Aeneid in such a generalized form that it applies to the entire Roman history and to the entire Roman people. According to Virgil, Augustus is only the most prominent representative and spokesman of the entire Roman people.

Note that from a formal point of view, the idea of the Trojan origin of Rome is in complete contradiction with an Italian idea. According to one version, the Roman kings are descended from Aeneas and, therefore, from Venus, and according to another version, they are from Mars and Rhea Silvia. Let us add to this that in the Aeneid itself, purely Italian patriotism is presented extremely expressively. Strength, power, courage, battle-hardenedness, and devotion to the homeland of the Italians are sharply contrasted in Numan's dying speech with Phrygian effeminacy, a penchant for aesthetic pleasures, lethargy and laziness. Jupiter himself, in canto I and canto XII, intends to create a Roman state based on a mixture of Italians and Trojans, but with a clear superiority of the Italians, since the Roman people will not accept either the morals and customs, nor the language, nor the name of the Trojans, but will accept, according to Jupiter, only their blood.. (The rudeness and hardening of the Italians is successfully demonstrated, for example, by the fact that the Italianized Greek Evander puts Aeneas to sleep on dry leaves and a bear skin.) Consequently, in its final form, Virgil’s ideology produces Roman kings also from Mars and Rhea Silvia , but understands this latter as a descendant of Aeneas, and not as an original Italian (following Naevius and Ennius, who made Rhea Silvia not even a distant descendant of Aeneas, but directly his daughter). Thus, Virgil wants to unite the healthy, strong, but rude Italian people, led by Mars, with the noble, refined and cultural Trojan world, led by Venus.

c) The artistic reality of Virgil's Aeneid is distinguished by purely Roman and even emphatically Roman features. Roman poetry is distinguished by a monumental style combined with enormous detail, reaching the point of naturalism. However, both were sufficient in ancient literature even before Virgil. We find features of monumentality in Homer, Aeschylus and Sophocles, in the Roman epics and Lucretius, just as affective psychology is sufficiently represented in them. But in Rome and especially in Virgil these features artistic style brought to such a development that transfers them to a new quality. Monumentality is brought to the level of depicting the world Roman power, and individualism is embodied here in an extremely mature and even overripe psychology, depicting not only titanic feats, but hesitation and uncertainty, reaching deep conflicts, intense passions and premonitions of disasters. This complex Hellenistic-Roman style of Virgil can be observed both in the artistic reality of his poems, including things, people, gods and fate, and in the form of depiction of this reality, including epic, lyricism, drama and oratory in their incredible interweaving.

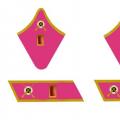

d) Let us point to the image of things in Virgil. These items are shown to be luxurious and designed to make a deep impression. Song XII depicts how, before the duel between Aeneas and Turnus, King Latinus rides in a four-horse chariot and his brow is surrounded by 12 golden rays. Turnus arrives on a white pair and brandishes two broad spears. Aeneas sparkles with a star shield and celestial weapons.

About the work of Hephaestus (Vulcan) in Homer we only read a mention of a hammer with an anvil, tongs, furs and clothes of the worker and speaks of a strong back, chest and his sinewy arms. Virgil depicts a grandiose and terrible underground factory, striking with its thunder, brilliance and its cosmic works such as thunder, thunderstorms, clouds, rain, winds, etc. While on the shield of Achilles in Homer there are pictures of an astronomical and everyday nature, on the shield of Aeneas in Virgil (VIII, 617-731) depicts the entire grandiose history of Rome, showing its greatest figures and the world power of Rome, all of which sparkles and glows, and all of Aeneas’s weapons are compared to how a gray cloud lights up from the sun’s rays. The monumentality and colorfulness of the image is evident here.

Nature in Virgil also bears the features of Roman poetry. Here, grandiosity is often mixed with very great detail, accompanied by detailed analysis various psychological experiences. It is worth reading at least the image of a storm at sea in Cantos I (50-156).

In contrast, the peaceful silence of the night, and also with different details, is depicted in canto IV (522-527).

Evander, walking with Aeneas near the future Rome, shows his companion groves, rivers, cattle; In general, a peaceful, idyllic environment is depicted (VIII). Particular attention is drawn to the idyllic nature of Elysium in the underworld (VI, 640-665). Here the ether and fields are clothed in purple light. People here and there recline on the grass and feast. There are fragrant laurels in the forest. It has its own sun and its own stars. Many spend their time in games and competitions in the lap of nature. Horses graze in the meadows. However, the image of the Sibyl's cave (VI), as well as the dirty and stormy underground river Acheron and surrounded by a fiery river, is shrouded in gloomy horror. underground city in Tartarus with a triple wall, adamantine pillars and an iron tower to the sky (VI, 558-568). This kind of painting is almost always given in the context of depicting powerful heroes, the founders of Rome.

e) People in their relationship with the gods - this main subject artistic reality in Homer - in Virgil are always depicted in positions full of drama. It is not for nothing that Aeneas is often called here “pious” or “father.” He is entirely in the hands of the gods and does not create his own will, but the will of fate. In Homer, the gods also constantly influence the lives of people. But this does not prevent Homer’s heroes from making their own decisions, which often coincide with the will of the gods, and often contradict them. In Virgil, everyone lies prostrate before the gods, and the complex psychology of the heroes, if it is depicted, is always at odds with the gods.

Historical paintings of Rome on a shield, made by Vulcan, give Aeneas pleasure, but, according to Virgil, he does not know the events themselves (VIII, 730). Aeneas leaves Troy in a direction that is completely unknown to him. He ends up with Dido, having no intention of meeting the Carthaginian queen. He arrives in Italy - no one knows why. Only Anchises in the underworld tells him about his role, but this role does not make him happy. He wanted to stay in Troy; and when he got to Dido, he would like to stay with Dido; when he got to Latinus, he wanted to stay with Latinus and marry Lavinia. However, fate itself predetermines that he become the founder of Rome, and all he can do is ask the oracles, offer prayers and make sacrifices. Aeneas submits to the gods and fate against his own will.

The poet simultaneously shows how simple and immediate religious faith was lost in his times. At every step he forcibly forces the reader to recognize this faith and see its ideal examples.

Dido, the other main character of the Aeneid, despite all her opposition to Aeneas, again repeats religious concept Virgil. This is a powerful and strong woman, who feels her duty to her late husband; she is blinded by the heroic fate of Aeneas and experiences deep love for him, so that for this reason alone she is torn apart by an internal and, moreover, severe conflict. Such internal conflict ancient literature did not know until Euripides and Apollonius of Rhodes. But Virgil further deepened and aggravated this conflict. When Aeneas leaves Dido, she, full of love for him and at the same time cursing him, throws herself into the fire and immediately pierces herself with a sword. Virgil sympathizes with Dido’s experiences, but seems to want to say that this is what disobedience to the gods leads to.

Turnus is another confirmation of Virgil’s religious-psychological concept. As a leader and warrior, and even as an orator, he has a restless character. He was destined by fate to destroy the Trojans who came to Italy. He loves Lavinia and goes to war because of her. Therefore, his personal feelings coincide with the purpose of fate. He inspires constant sympathy. But here we read about Turnus’s reluctance to fight the Trojans and about the influence of the fury Allecto on him (VII, 419-470). This fury appears to Turnus in the form of an old prophetess, but soon reveals her true face:

Erinyes hissed in so many

Serpent, this is how her face appeared; burning rotating

The gaze, while he hesitated and tried to say more,

She pushed him away, raised two serpents from her hair,

She slammed the whip and opened her mouth so fiercely... (Bryusov.)

With a menacing speech, she throws a torch at Turnus and pierces his chest with a torch that breathes black flame. He is seized with immense horror, sweats profusely, rushes about on his bed, searches for a sword and begins to burn with the rage of war. Even heroes devoted to deities and fate still experience violence from them. Natural spiritual gentleness forced Virgil to find sympathetic traits in another enemy of the Trojans - the old man Latinus. Virgil has a gentle and humane attitude towards both fighting sides at the same time. With great sorrow he depicts the death of Priam at the hands of the boy Pyrrhus. Positive and negative heroes (Mezentius, Sinon, Drank) are presented from both the Greek and Italian sides, and everyone does the will of fate.

The gods of Virgil's wife are in a calmer form. Roman discipline meant that Jupiter was not as powerless and insecure as Homer's Zeus. In the Aeneid, he is the only director of human destinies, while other gods are incomparable to him in this regard. In Canto I, Venus addresses Jupiter as an absolute ruler, and he solemnly declares to her: “My decisions are unchangeable” (260). Indeed, the picture he paints of the future destinies of Rome and the clashes of entire nations is predetermined by him down to the smallest detail. Venus addresses him with the words (X, 17 et seq.): “Oh, the eternal power of both people and events, my father! Besides, who should we beg?” An omnipotent ruler, but at the same time noble and merciful, he turns out to be in conversation even with the ever-rebellious Juno, who does not dare to object to him (XII). In contrast to the softer and more peaceful Venus, Juno is depicted as restless and malicious. One has only to read about how Jupiter is trying to reconcile Venus and Juno (X) to be convinced of the relatively flexible nature of Venus. Rumor is demonic, brutally merciless, sowing discord among people and not distinguishing between good and evil (IV).

Apollo, Mercury, Mars and Neptune are depicted in impeccable form. The highest deities in Virgil are depicted more or less sublimely, in violation of traditional polytheism. In addition, they (in contrast to Homer) are very disciplined and do not act at their own risk or fear. Jupiter rules everything, and all the gods are divided, so to speak, into some kind of class. Each has its own function and its own specialty. They are characterized by a purely Roman subordination, and, for example, Neptune, the god of the sea, is indignant that it is not he, but some minor deity Aeolus, who must tame the winds.

The intervention of gods, demons and dead people in the lives of living people not only fills the entire Aeneid, but is almost always characterized by an extremely dramatic, violent character. In addition, all these appearances of the gods, predictions and signs in the Aeneid almost always do not have some narrow everyday or even simple military character, but they are always historical in the sense of contributing to the main goal of the entire Aeneid - to depict the future power of Rome. The gods entering the battle behave violently during the fire of Troy. Amid fire, smoke, chaos of stones and destruction of houses, Neptune shakes the walls of the city and the entire city at its very foundation. Juno, girded with a sword and occupying the Skeian Gate, shouts furiously, calling on the Greeks. Pallas Athena, illuminated by a halo and terrifying everyone with her Gorgon, sits on the fortress walls of Troy. Jupiter himself excites the troops (II, 608-618). During the fire of Troy, the ghost of Hector, who was killed by Achilles shortly before, appears to Aeneas in a dream. Hector, after Achilles’ abuse of him, is not only sad, he is black with dust, bloody, his swollen legs are entangled in belts, his beard is covered in dirt, his hair is stuck together with blood, there are gaping wounds on him. With deep lamentation, he orders Aeneas to leave Troy, entrusting him with the shrines of Troy (I, 270-297).

When Aeneas appears in Thrace and wants to tear a plant out of the ground for a sacrifice, he sees black blood on the trunks of the plant and hears a mournful voice from the depths of the hill. It was the blood of Polydor (son of Priam), killed by the Thracian king Polymestor (III, 19-48).

Fate is against the marriage of Aeneas and Dido, and so, when Dido makes sacrifices, the sacred water turns black, the wine brought turns into blood, a voice is heard from the temple of her deceased husband, a lonely owl moans on the towers. In Homer, Zeus sends Hermes to Kirke with the order to release Odysseus, and she releases him only with some dissatisfaction. In Virgil, Jupiter also sends Mercury to Aeneas with a reminder of his departure (IV). After this, the tragic story of Dido plays out. And when Aeneas, having boarded the ship, fell asleep peacefully, Mercury appears to him in a dream for the second time. Mercury hurries Aeneas and speaks of the possible intrigues of Dido (IV, 5.53-569).

In Homer, Odysseus descends to Hades to find out his fate. In Virgil, Aeneas descends into Hades to find out the fate of thousand-year-old Rome. In a conversation with Aeneas, the Sibyl is presented as completely frantic (VI, 33-102):

When I said that

In front of the doors, her suddenly appearance, a single color

And in disorder the hair has changed;

And the heart rises in a wild frenzy; and it seems

She is taller, she does not speak like people, she is covered in will

Close god already (46-51). (Bryusov.)

In a more peaceful form, Tiberin, the god of the Tiber River, appears to Aeneas, among the poplar thickets, covered with azure muslin and with reeds on his head, but he again speaks of the creation of a new kingdom (VIII, 31-65).

In Crete, the Penates appear to Aeneas and announce that Italy is the ancient homeland of the Trojans and that he should go there to create Trojan power (III). Venus gives a sign to Aeneas about war, again among menacing phenomena (VIII, 524-529):

For suddenly the ether trembled, a radiance flashed

With thunder and ringing, and everything suddenly disappeared from view,

And the Tyrrhenian trumpet began to howl in the air.

They looked, and again and again a huge roar was heard.

They see how among the clouds, where the sky is clear, weapons

It glows in the azure distance and thunders, clanking against each other. (S. Solovyov.)

The intervention of the gods in the affairs of people is especially frequent in songs IX-XII, where war is depicted; Virgil everywhere wants to depict something wonderful or unusual. If Homer wants to make everything supernatural completely natural, ordinary, then with Virgil it’s just the opposite. In Homer, Pallas Athena, in order to hide Odysseus from the Phaeacians, envelops him in a thick cloud, but this happens in the evening (Od., VII). In Virgil, Aeneas and Achates are enveloped in a cloud in broad daylight, so the miraculousness of this phenomenon is only emphasized. When people are depicted by Virgil outside of any mythology, they are also distinguished by his increased passion, often reaching the point of hesitation and uncertainty, to insoluble conflicts. The love of Dido and Aeneas ignites in a cave, where they are hiding from a terrible storm and sudden mountain streams (IV). Aeneas is full of hesitation. In this difficulty, he prays to the gods, makes sacrifices and asks the oracles. At the decisive moment of the victory over Turnus, when the latter begs him for mercy in touching words, he hesitates whether to kill him or leave him alive, and only Pallante’s belt with plaques is noticed him on Tournai, forced him to put an end to his enemy (XII, 931-959).

The main characters of the Aeneid are, strictly speaking, Juno and Venus. But they, too, constantly change decisions, hesitate, and their enmity is devoid of principles and often becomes petty. Touching is the unfortunate Creusa, the disappeared wife of Aeneas, who even after her death still cares about Aeneas himself and their boy Ascanius (I, 772-782). Andromache is also touching, also having experienced endless disasters and still yearning for her Hector , even after marrying Helen (III). Palinur's request for his burial is heartbreaking, since he remains unburied in a foreign country (VI). Euryalus's mother, having learned about the death of her son, gets cold feet, knitting needles fall out of her hands, and falls yarn; in madness, with her hair torn, she runs away to the troops and fills the sky with groans and lamentations (IX, 475-499). Evander, almost unconscious, falls on the body of his dead son Pallant and also furiously moans and laments passionately and helplessly (XI) In contrast to this, the Trojans Nisus and Euryalus, two devoted friend soldier's friend; they die as a result of mutual devotion (IX, 168-458).

Not only Dido resorts to suicide, but also Latinus’s wife, Amata, shocked by the defeat of her relatives (XII). Virgil did not ignore the simple life of ordinary workers, which, obviously, was also well known to him (VIII, 407-415).

f) The genres in the Aeneid are very diverse, which was the norm for Hellenistic-Roman poetry. First of all, this is, of course, an epic, that is, a heroic poem, the source of which was Homer, as well as the Roman poets Naevius and Ennius, along with the Roman annalists. Virgil borrows mass from Homer individual words, expressions and entire episodes, differing from its simplicity with enormous psychological complexity and nervousness.

The epic genre also manifests itself in Virgil in the form of many epillia, in which one cannot help but see some influence of neotericism. Almost every canto of the Aeneid is a complete epillium. But even here, socio-political ideology once and for all separated Virgil from the carefree small forms of the neo-territics, who often wrote in the style of art for art’s sake.

Virgil’s lyricism is also clearly represented, examples of which are visible in the laments of Evander and the mother of Euryalus. But what especially sharply distinguishes Virgil's epic from other epics is its constant, sharp drama, the tragic pathos of which sometimes reaches the level of tragedy.

As for prose sources, the influence of Stoicism (Aeneas’s stoic obedience to fate) is undeniable in the Aeneid. The Aeneid is further filled with rhetoric (a mass of speeches, many of which are composed very skillfully and require special analysis). Virgil, as we have seen, is also no stranger to descriptions, which are also very far from the calm and balanced epic and are sprinkled with dramatic and rhetorical elements. These descriptions relate to nature, to a person’s appearance, to his behavior, to his weapons, and to numerous battles. Rhetoric, like Virgil’s varied Hellenistic scholarship in general, testifies to the poet’s long study of numerous prose materials. He also made his trip to Greece to study various materials for his poem. All of these genres are by no means presented in an isolated form in Virgil - this is a complete and unique artistic style, which is often epic only in form, but in essence it is impossible to even say which of these genres prevails in such a picture as the taking of Troy, for example. in a novel, for example, like that of Dido and Aeneas, and in such a duel, for example, as between Aeneas and the Turk. This is Hellenistic-Roman diversity, accompanied, moreover, by typically Hellenistic scholarship.

g) The artistic style of the Aeneid, resulting from this variety of genres, is also extremely far from the simplicity of the classics and is filled with numerous and contradictory elements that make an indelible impression on the reader.

The whole originality of Virgil’s artistic style lies in the fact that his mythology is indistinguishable from historicism. Everything in Virgil is filled with history. The origin of Rome, its growing power and the Principate that eventually emerged are the ideas to which almost every artistic technique in his work is subordinated, even such as, for example, description or speech.

However, this historicism should not be understood as only an objective ideology or as only an objective picture of the history of Rome. All these methods of objective depiction were deeply and passionately experienced by Virgil; his emotions often reach an ecstatic state. Therefore, psychologism, and, moreover, psychologism of an amazing nature, is also one of the most essential principles of the artistic style of the poem.

The construction of artistic images in the Aeneid is distinguished by great rationality and organizational power, which could not but be here, since the entire poem is a glorification of a powerful world empire. There is nothing frail or unbalanced in Virgil’s psychologism. All hysterical characters (Sibyl, Dido) are complex psychologically, but are strong in their organization and logical consistency in their actions. Virgil builds on this the entire positive ideological side of his artistic style. This style often pursues educational goals, since the entire poem was written solely for the preaching of ancient ascetic ideals, for the restoration of strict antiquity in this age of depravity, for the restoration of an ancient and harsh religion with all its wonders and signs, its oracles, its social and ancient morality. Virgil in his poetics is one of the greatest ancient moralists. His moralism is filled with the most sincere and most sincere condemnation of war and love for simple and peaceful rural life. In Virgil, absolutely all the heroes not only suffer from the war, but also die from it, except perhaps Aeneas. However, Aeneas also gives instructions to his son (XII, 435 et seq.):

Valor, youth, learn from me tireless labors,

Fortunately - alas! - other's. (S. Solovyov.)

Anchises says to Aeneas (VI, 832-835):

O children, do not accustom your souls to such discords,

Do not turn your fatal power on the heart of your homeland.

You are the first to leave your family leading from Olympus,

Drop the sword from your hands, you who are my blood! (Bryusov.)

Not only does Turnus ask Aeneas for mercy, but Drunk also addresses Turnus with the following words (XI, 362-367):

There is no salvation in battle, and we all demand peace,

Turnus, you also have to seal the world with an indestructible pledge.

I myself am the first, whom you consider to be an enemy, and with this

I won’t argue, I come with a prayer. Have pity on yours!

Throw away your pride and walk away amazed. Looked pretty good

We, broken, have a funeral feast and devastation of huge villages. (S. Solovyov.)

Virgil is thus a man of a soft soul, cordial and peaceful mood, not only in the Bucolics and Georgics, but also in the Aeneid, and here, perhaps, most of all. One of the incorrect views regarding the artistic style of the Aeneid is that it is a far-fetched and fantastic work, far from life, filled with mythology, in which the poet himself does not believe. Therefore, the supposed artistic style of the Aeneid is the opposite of any realism. But realism is a historical concept, and ancient realism, like any realism in general, is quite specific. In the eyes of the builders and contemporaries of the rising Roman Empire, the artistic style of the Aeneid is undoubtedly realistic. Did Virgil believe in his mythology or not? Of course, there can be no talk of any naive and literal mythological belief in this age of high civilization. However, this does not mean that Virgil’s mythology is pure fantasy. Mythology is introduced in this poem solely for the purpose of generalizations and justifications of Roman history. According to Virgil, the Roman Empire arose as a result of the immutable laws of history. He expressed all this immutability with the help of the invasion of mythical forces into history, since the ancient world was generally unable to substantiate this immutability in any other way. Thus, the artistic style of the Aeneid is the true realism of the period of the rising Roman Empire.

To this it is necessary to add the fact that Virgil’s gods and demons ultimately themselves depend on fate, or fate (the words of Jupiter in Song X, 104-115).

Finally, all those nightmarish visions and hysteria, of which there are so many in the Aeneid, also represent a reflection of the bloody and inhuman reality of the last century of the Roman Republic with its proscriptions, the mass destruction of innocent citizens, and the unprincipled struggle of political and military leaders.

One could cite many texts from Roman historiography that paint the last century of the Roman Republic in even more nervous and nightmarish tones than we find in the Aeneid.

In the same sense, it is necessary to talk about the nationality of the Aeneid. Nationality is also a historical concept. In the strictly defined and limited sense in which one can talk about the realism of the Aeneid, one must also talk about its nationality. "The Aeneid" is a work of ancient classicism, complex, learned and overloaded with psychological detail. But this classicism is a reflection of an equally complex and confusing period of ancient history.

The Aeneid cannot in any way be placed on the same plane as the poems of the so-called “false classicism” of new literature.

Finally, its external side is in full accordance with all the noted features of the artistic style of the Aeneid.

The style of “The Aeneid” is distinguished by a compressed and intense character, which is noticeable in almost every line of the poem: either it is the artistic image itself, ardent and restrained at the same time, or it is some short, but sharp and apt verbal expression. Numerous expressions of this kind became sayings already in the first centuries after the appearance of the poem, entered world literature and remain so in literary use to this day. This strong, artistically expressive verse of the poem masterfully uses longitude for semantic purposes where we would expect a short syllable, or puts a monosyllabic word at the end of the verse and thereby sharply emphasizes it; There are numerous alliterations and verbal sound notation, which only those who have read the Aeneid in the original have an idea about. Such tension and maximum conciseness, lapidary stylistic devices are characteristic of the Aeneid.

"The Aeneid" is a mythological poem with a historical perspective, linking myth and modernity. By updating the great mythological epic, Virgil entered - according to ancient ideas - into “competition” with Homer. This meant a complete break with the aesthetic principles of Alexandrinism.

Virgil did not have time to finish the Aeneid before his death and asked not to publish it, but Augustus did not listen.

The plot of the Aeneid falls into two parts: Aeneas wanders, then fights in Italy. Virgil devoted six books to each of these parts. The first half of the poem is thematically close to the Odyssey, the second half to the Iliad. Aeneas “fugitive by fate”; The reference to "fate" not only serves as a justification for Aeneas's flight from Troy, but also indicates the driving force of the poem.

The narrative begins with the last wanderings of Aeneas, and the preceding events are given as the hero's story about his adventures.

When Aeneas and his flotilla are already approaching Italy, the final destination of the voyage, the angry Juno sends a terrible storm. The ships are scattered across the sea, and the exhausted Trojans land on unknown shores. And then the narrative is interrupted by a scene on Olympus: Jupiter reveals to Venus the future fate of Aeneas and his descendants, up to the time of Augustus, and predicts the power and greatness of the Roman power. In the further course of the story, the Olympic plan continues to alternate with the earthly one, and human motivations are duplicated by divine suggestions. The stubborn hostility of Juno is opposed by the loving care of Venus, the hero’s mother. The heroes sail to Libya to Carthage, which is under construction. This powerful city was founded by an energetic woman, Queen Dido, who fled from Tyre after her beloved husband Sychaeus was treacherously killed by her brother Pygmalion.

The first book ends with an exposition of Dido's love for Aeneas. In general structure, it reproduces the scheme of books 5 - 8 of the Odyssey: the voyage of Odysseus, the storm raised by Poseidon, and the arrival in the country of the Phaeacians, a warm welcome from King Alcinous, in whose country they are already singing about the Trojan War, and a request to tell about the adventures.

From the “borrowings” a new whole is created, with an increased emphasis on aspects of lyricism and subjective motivation of action that are alien to the Homeric epic. Aeneas' story occupies the second and third books.