The most famous ancient Greek orators. Oratory as a prototype of journalism

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Hosted at http://www.allbest.ru/

Introduction

1.1 Gorgias

1.3 Demosthenes

2. Hellenistic era

2.1 Dio Chrysostom

2.2 Aelius Aristides

3.1 Cicero

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction orator genre hellenism greece

Public speech was the most widespread genre among the educated people of antiquity. The knowledge that gives people the command of oral speech, which occupies the minds and hearts of people, was called rhetoric.

In terms of the place occupied in the art of the artistic word of ancient Hellas, rhetoric was comparable to such genres of art as the heroic epic or classical Greek drama. Of course, such a comparison is valid only for the era in which these genres coexisted. speaker genre hellenism greece

Subsequently, in terms of the degree of influence on the development of later European literature, rhetoric, which still played a significant role in the Middle Ages, in modern times gave way to other genres of literature that determined the nature of the national cultures of Europe for many centuries.

It should be especially noted that of all types of artistic expression in the ancient world, public speech was most closely connected with its contemporary political life, social system, level of education of people, way of life, way of thinking, and finally, with the peculiarities of the development of the culture of the people who created this genre.

1. Oratory in Ancient Greece

Love for a beautiful word, a lengthy and magnificent speech, replete with various epithets, metaphors, comparisons, is already noticeable in the earliest works of Greek literature - in the Iliad and the Odyssey. In the speeches uttered by the heroes of Homer, admiration for the word, its magical power is noticeable - so, it is always “winged” there and can strike like a “feathered arrow”. Homer's poems make extensive use of direct speech in its most dramatic form, dialogue. In terms of volume, the dialogic parts of the poems far exceed the narrative ones. Therefore, the heroes of Homer seem unusually talkative, the abundance and fullness of their speeches is sometimes perceived by the modern reader as prolixity and excess.

The very nature of Greek literature favored the development of oratory. It was much more "oral", so to speak, more designed for direct perception by listeners, admirers of the author's literary talent. Having become accustomed to the printed word, we do not always realize what great advantages the living word, which sounds in the mouth of the author or reader, has over the written word. Direct contact with the audience, richness of intonation and facial expressions, plasticity of gesture and movement, and finally, the very charm of the speaker's personality make it possible to achieve a high emotional upsurge in the audience and, as a rule, the desired effect. Public speaking is always an art.

In Greece of the classical era, for the social system of which the form of a city-state, a polis, in its most developed form - a slave-owning democracy, is typical, especially favorable conditions were created for the flourishing of oratory. The supreme body in the state, at least nominally, was the People's Assembly, to which the politician addressed himself directly. In order to attract the attention of the masses (demos), the speaker had to present his ideas in the most attractive way, while convincingly refuting the arguments of his opponents. In such a situation, the form of speech and the skill of the speaker played, perhaps, no less a role than the content of the speech itself.

1.1 Gorgias

The largest theoretician and teacher of eloquence in the 5th century BC. e. was Gorgias from the Sicilian city of Leontina. In 427, he arrived in Athens, and his skillful speeches attracted everyone's attention. Later, he traveled all over Greece, speaking to audiences everywhere. At the meeting of the Greeks in Olympia, he addressed the audience with a call for unanimity in the struggle against the barbarians. The Olympic speech of Gorgias glorified his name for a long time (a statue was erected to him in Olympia, the base of which was found in the last century during archaeological excavations).

Tradition has preserved little of the creative heritage of Gorgias. For example, the following advice to the speaker has been preserved: "Refut the serious arguments of the opponent with a joke, jokes with seriousness." Only two speeches attributed to Gorgias have survived in their entirety - “Praise to Helen” and “Justification of Palamedes”, written on the plots of myths about the Trojan War. The oratory of Gorgias contained many innovations: symmetrically constructed phrases, sentences with the same endings, metaphors and comparisons; the rhythmic articulation of speech and even rhyme brought his speech closer to poetry. Some of these techniques have retained the name "Gorgian figures" for a long time. Gorgias wrote his speeches in the Attic dialect, which is a clear evidence of the increased role of Athens in the literary life of ancient Hellas.

Gorgias was one of the first orators of a new type - not only a practitioner, but also a theorist of eloquence, who taught young men from wealthy families to speak and think logically for a fee. Such teachers were called sophists, "experts in wisdom." Their "wisdom" was skeptical: they believed that absolute truth does not exist, the true is that which can be proved in a sufficiently convincing way. Hence their concern for the persuasiveness of the proof and the expressiveness of the word: they made the word the object of a special study. Especially a lot they were engaged in the origin of the meaning of the word (etymology), as well as synonymy. The main field of activity of the sophists was Athens, where all genres of eloquence flourished - deliberative, epidictic and judicial.

The most outstanding Athenian orator of the classical era in the field of judicial eloquence was undoubtedly Lysias (c. 415--380 BC). His father was a metek (a free man, but without civil rights) and owned a workshop in which shields were made. The future speaker, together with his brother, studied in the southern Italian city of Furii, where he listened to a course in rhetoric from famous sophists. Around 412, Lysias returned to Athens. The Athenian state at that time was in a difficult position - the Peloponnesian War was going on, unsuccessful for Athens. In 405, Athens suffered a crushing defeat. After the conclusion of a humiliating peace, proteges of the victorious Sparta, the “30 tyrants”, came to power, pursuing a policy of cruel terror in relation to the democratic and simply powerless elements of Athenian society. The large fortune owned by Lysias and his brother was the reason for the massacre of them. Brother Lysias was executed, the orator himself had to flee to neighboring Megara. After the victory of democracy, Lysias returned to Athens, but he did not succeed in obtaining civil rights. The first judicial speech delivered by Lysias was against one of the thirty tyrants responsible for the death of his brother. In the future, he wrote speeches for other people, making this his main profession. In total, up to 400 speeches were attributed to him in antiquity, but only 34 have come down to us, and not all of them are genuine. The vast majority of those that have survived belong to the judicial genre, but in the collection we find both political and even solemn speeches - for example, a funeral word over the bodies of soldiers who fell in the Corinthian war of 395-386. The characteristic features of the Lysias style are clearly noted by the ancient critics. His presentation is simple, logical and expressive, the phrases are short and symmetrical, the oratorical techniques are refined and elegant. Lysias laid the foundation for the genre of judicial speech, creating a kind of standard of style, composition and argumentation itself - subsequent generations of orators followed him in many respects. Especially great are his merits in the creation of the literary language of Attic prose. We will not find in him either archaisms or confusing turns, and subsequent critics (Dionysius of Halicarnassus) admitted that no one subsequently surpassed Lysias in the purity of Attic speech. What makes the story of the speaker alive and graphic is the description of the character (etopea) - and not only the characters of the persons depicted, but also the character of the speaking person (for example, the stern and simple-hearted Euphilet, in whose mouth the speech "On the murder of Eratosthenes" is put).

1.3 Demosthenes

The greatest master of oral, predominantly political, speech was the great Athenian orator Demosthenes (385-322). He came from a wealthy family - his father owned workshops in which weapons and furniture were made. Very early, Demosthenes was orphaned, his fortune fell into the hands of his guardians, who turned out to be dishonest people. He began his independent life with a process in which he spoke out against the robbers (the speeches he made in connection with this have been preserved). Even before that, he began to prepare for the activity of an orator and studied with the famous Athenian master of eloquence, Isei. The simplicity of the style, the conciseness and significance of the content, the strict logic of the proof, the rhetorical questions - all this was borrowed by Demosthenes from Isaius.

From childhood, Demosthenes had a weak voice, besides, he burr. These shortcomings, as well as the indecision with which he kept himself on the podium, led to the failure of his first performances. However, by hard work (there is a legend that, standing on the seashore, he recited poetry for hours, drowning out the noise of coastal waves with the sounds of his voice), he managed to overcome the shortcomings of his pronunciation. The orator attached particular importance to the intonational coloring of the voice, and Plutarch in the biography of the speaker gives a characteristic anecdote: “They say that someone came to him with a request to make a speech in court in his defense, complaining that he was beaten. "No, nothing like that happened to you," said Demosthenes. Raising his voice, the visitor shouted: “How, Demosthenes, this didn’t happen to me ?!” “Oh, now I clearly hear the voice of the offended and injured,” said the speaker.

At the beginning of his career, Demosthenes delivered court speeches, but later he became more and more involved in the turbulent political life of Athens. He soon became a leading political figure, often speaking from the podium of the People's Assembly. He led a patriotic party that fought against the Macedonian king Philip, tirelessly calling on all Greeks for unity in the fight against the "northern barbarian." But, like the mythical prophetess Cassandra, he was destined to proclaim the truth without meeting understanding or even sympathy.

Philip began his onslaught on Greece from the north - he gradually subjugated the cities of Thrace, took possession of Thessaly, then established himself in Phokis (Central Greece), sending his agents even to the island of Euboea, in the immediate vicinity of Athens. The first war of Athens with Philip (357-340) ended in a Philocratic peace unfavorable for Athens, the second (340-338) ended in a crushing defeat of the Greeks at Chaeronea, where Demosthenes fought as an ordinary fighter. The two most famous speeches of Demosthenes are associated with these events. After the Peace of Philocrates, he denounced his perpetrators in the speech “On the Criminal Embassy” (343), and after Chaeronea, when it was proposed to reward the orator with a golden wreath for services to the fatherland, he had to defend his right to this award in the speech “On the Wreath” ( 330). The great orator was destined to survive another defeat of his homeland, in the Lamian War of 322, when the Greeks, taking advantage of the confusion after the death of Alexander the Great, opposed his successors.

This time the Macedonian troops captured Athens. Demosthenes, along with other leaders of the patriotic party, had to flee. He took refuge in the temple of Poseidon on the island of Kalavria. The Macedonian soldiers who overtook him there wanted to take Demosthenes out by force, so he asked for time to write a letter to his friends, took a papyrus, thoughtfully raised a reed pen to his lips and bit it. In a few seconds, he fell dead - a fast-acting poison was hidden in the reeds.

In the literary heritage of Demosthenes (61 speeches have come down to us, but not all, apparently, are genuine), it is precisely political speeches that determine his place in the history of Greek oratory. They are very different from the speeches of Isocrates. So, for example, the introduction in the speeches of Isocrates is usually drawn out; on the contrary, since Demosthenes' speeches were delivered on burning topics and the speaker was supposed to immediately attract attention, the introduction to his speeches was for the most part short and energetic. Usually it contained some kind of maxim (gnome), which was then developed on a specific example. The main part of Demosthenes' speech is the story - the presentation of the essence of the matter. It is built unusually skillfully, everything in it is full of expression and dynamics. There are also ardent appeals to the gods, to listeners, to the very nature of Attica, and colorful descriptions, and even an imaginary dialogue with the enemy. The flow of speech is suspended by the so-called rhetorical questions: “What is the reason?”, “What does this really mean?” etc., which gives the speech a tone of extraordinary sincerity, which is based on genuine concern for the matter.

Demosthenes made extensive use of tropes, in particular metaphor. The source of the metaphor is often the language of the palestra, the gymnastic stadium. Opposition, antithesis is used very elegantly - for example, when “the current century and the past century” are compared. The method of personification used by Demosthenes seems unusual to the modern reader: it consists in the fact that inanimate objects or abstract concepts act as persons defending or refuting the arguments of the orator. The combination of synonyms in pairs: “look and observe”, “know and understand” - contributed to the rhythm and elevation of the syllable. A spectacular technique found in Demosthenes is the “silence figure”: the speaker deliberately keeps silent about what he would certainly have to say in the course of the presentation, and the listeners inevitably supplement it themselves. Thanks to this technique, the listeners themselves will draw the conclusion necessary for the speaker, and he will thereby significantly gain in persuasiveness.

2. Hellenistic era

The time that came after the fall of free polis Greece is commonly called the era of Hellenism. Political eloquence had less and less place in public life, interest in the content of speeches gave way to an interest in form. The rhetoric schools studied the speeches of former masters and tried to slavishly imitate their style. Fakes of the speeches of Demosthenes, Lysias and other great orators of the past are spreading (such fakes have come down to us, for example, as part of the collection of Demosthenes' speeches). The names of Athenian orators who lived in the period of early Hellenism and consciously composed speeches in the spirit of old models are known: for example, Charisius composed judicial speeches in the style of Lysias, while his contemporary Democharus was known as an imitator of Demosthenes. This tradition of imitation was then called "atticism". At the same time, a one-sided interest in the verbal form of eloquence, which became especially noticeable in the new Greek cultural centers in the East - Antioch, Pergamum and others, gave rise to the opposite extreme, a passion for deliberate mannerism: this style of eloquence was called "Asiatic". Its most famous representative was Hegesias from Asia Minor Magnesia (mid-III century BC). Trying to outdo the speakers of the classical era, he chopped periods into short phrases, used words in the most unusual and unnatural sequence, emphasized rhythm, heaped up paths. The flowery, pompous and pathetic style brought his speech closer to melodic declamation. Unfortunately, the oratory of this era can only be judged by a few surviving quotations - almost no whole works have come down to us. However, the works of orators of the Roman time have come down to us in large numbers, mainly continuing the traditions of eloquence of the Hellenistic era.

2.1 Dio Chrysostom

Dion Chrysostom ("Chrysostom" - c. 40--120 AD) was a native of Asia Minor, but spent his young and mature years in Rome. Under the suspicious emperor Domitian (81-96), the orator was accused of malice and went into exile. He spent a long time wandering, earning his livelihood by physical labor. When Domitian fell victim to a conspiracy, Dion again became respected, rich and famous, still continuing his travels throughout the vast Roman Empire, never stopping in one place for a long time.

Dion belonged to the type of orators who combined the talent of an artist with the erudition of a thinker, philosopher, connoisseur of science. Deeply engaged in the liberal arts, especially literature, he scorned the pompous chatter of street speakers, ready to talk about anything and glorify anyone (“Damned sophists,” as Dion calls them in one of his speeches). In philosophical views, he was an eclecticist, gravitating towards the Stoics and Cynics. Some of his speeches even resemble cynic diatribes, the protagonist in them is the philosopher Diogenes, famous for his eccentric antics. Here there is a resemblance to Plato, in whose dialogues his teacher Socrates is a constant character. The hero of Dion's speeches subjects the foundations of social, political and cultural life to devastating criticism, shows the vanity and futility of human aspirations, demonstrating the complete ignorance of people about what is evil and what is good. Many of Dion's speeches are devoted to literature and art - among them the Olympian Oration, glorifying the sculptor who created the famous statue of Zeus, and the paradoxical Trojan Speech, which jokingly turns inside out the myth of the Trojan War, sung by Homer, Dion's favorite writer.

In Dion's speeches there is also a lot of autobiographical material. He willingly and a lot talks about himself, while trying to emphasize how favorable the emperors of Rome were to him. It becomes clear why Dion in his works paid so much attention to the theory of an enlightened monarchy as a form of government, which he develops in four speeches "On royal power".

As for the style of Dion, already ancient critics especially praised him for having cleansed the literary language of vulgarisms, paving the way for pure Atticism, in which Aelius Aristides followed him.

2.2 Aelius Aristides

Aelius Aristides (c. 117-189) was also a native of Asia Minor and also wandered, visited Egypt, delivered speeches at the Isthmian Games and in Rome itself. Of his literary heritage, 55 speeches have been preserved. Some approach epistles in type (such is the speech in which he asks the emperor to help the city of Smyrna after the earthquake). Other speeches are exercises on historical topics, such as what might be said in the People's Assembly at such and such a critical moment in Athenian history in the 5th-4th centuries BC. e. Some of them are written on the themes of the speeches of Isocrates and Demosthenes. Among the speeches associated with modernity, the “Praise of Rome” (about 160) should be attributed: it exalts the Roman state system to the skies, combining the advantages of democracy, aristocracy and monarchy. Finally, among the surviving speeches, we also find "Sacred speeches", that is, speeches addressed to the gods - Zeus, Poseidon, Athena, Dionysus, Asclepius and others. They give allegorical interpretations of ancient myths, along with echoes of new religious trends associated with the penetration of foreign cults into Hellas. The content of some speeches was marked by the disease that the orator suffered - she made him a regular visitor to the temples of Asclepius, the god of healing. In honor of this god, the orator even composed poems: in the Asclepeion of Pergamon, a fragment of a marble slab was found with the text of a hymn, the author of which turned out to be Aelius Aristides.

Aristide's speeches were not improvisations; he prepared for them long and carefully. He was able to reproduce with great accuracy the manner of speech of the Attic orators of the 4th century BC. e., however, in some of his works he also uses the techniques of Asianists.

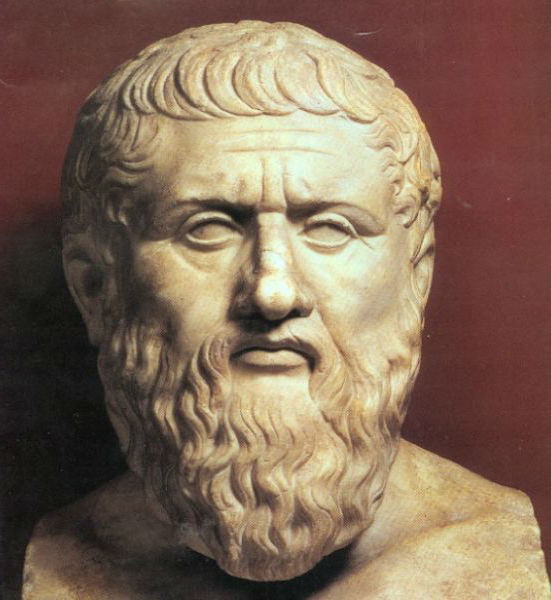

Aelius Aristides had a high opinion of his literary work and sincerely believed that he combined Plato and Demosthenes. But time proved to be a stricter judge, and it is now clear to us that he was only a shadow of the greatest orator of antiquity.

In the last period of its history, Hellenic eloquence gradually grew decrepit and degenerated. Its sunset, which took place in the full of dramatic events of the struggle of ancient ideology and religion with the advancing Christianity, was nevertheless majestic and glorious, and in many respects instructive. It is inextricably linked with the historical events of the 4th century AD. e. Thus, one of the most remarkable figures of late Greek rhetoric was none other than the emperor-philosopher Julian (322-363), who for his struggle against Christianity received the nickname of the Apostate. He is the author of talented polemical and satirical works, among which there are speeches (for example, the prose hymns "To the Mother of the Gods", "To the King of the Sun").

3. Oratory of ancient Rome

The development of eloquence in Rome was largely facilitated by brilliant examples of Greek oratory, which from the 2nd century. BC e. becomes the subject of careful study in special schools.

Passionate speeches were made by politicians, such as the reformers, the Gracchi brothers, especially Gaius Gracchus, who was an orator of exceptional power. Captivating the masses with the gift of words, he also used some theatrical techniques in his speeches. Among Roman speakers, for example, such a technique as showing scars from wounds received in the struggle for freedom was widespread.

Like the Greeks, the Romans distinguished two directions in eloquence: Asian and Attic. The Asian style, as you know, was characterized by pathos and an abundance of refined speech turns. Atticism was characterized by a concise, simple language, which was written by the Greek orator Lysias and the historian Thucydides. The Attic direction in Rome was followed by Julius Caesar, the poet Lipinius Calv, the republican Mark Julius Brutus, to whom Cicero dedicated his treatise Brutus.

But, for example, such an orator as Cicero developed his own, middle style, which combined the features of the Asian and Attic directions.

3.1 Cicero

Mark Tullius Cicero, the famous orator of antiquity, embodies, along with Demosthenes, the highest level of oratory.

Cicero lived from 106 to 43 BC. e. He was born in Arpin, southeast of Rome, descended from the equestrian class. Cicero received an excellent education, studied Greek poets, and was interested in Greek literature. In Rome, he studied eloquence with the famous orators Antony and Crassus, listened to and commented on the well-known tribune Sulpicius speaking at the forum, and studied the theory of eloquence. The orator needed to know Roman law, and Cicero studied it with the then popular lawyer Scaevola. Knowing the Greek language well, Cicero became acquainted with Greek philosophy through closeness with the Epicurean Phaedrus, the Stoic Diodorus, and the head of the new academic school, Philo. From him, he learned dialectics - the art of argument and argument.

Although Cicero did not adhere to a specific philosophical system, in many of his works he expounds views close to Stoicism. From this point of view, in the second part of the treatise "On the State", he considers the best statesman, who must have all the qualities of a highly moral person. Only he could improve morals and prevent the death of the state. Cicero's views on the best political system are set forth in the first part of this treatise. The author comes to the conclusion that the best state system existed in the Roman Republic before the Gracchi reform, when the monarchy was exercised in the person of two consuls, the power of the aristocracy was in the person of the senate, and democracy - in the people's assembly.

For a better state, Cicero considers it right to establish ancient laws, to revive the "custom of the ancestors" (treatise "On Laws").

Cicero also expresses his protest against tyranny in a number of works in which questions of ethics predominate: such are his treatises “On Friendship”, “On Duties”; in the latter, he condemns Caesar, directly calling him a tyrant. He wrote treatises "On the Limits of Good and Evil", "Tusculan Conversations", "On the Nature of the Gods". Cicero does not reject or approve the existence of the gods, however, he recognizes the need for a state religion; he resolutely rejects all miracles and fortune-telling (treatise "On fortune-telling").

Questions of philosophy had an applied character for Cicero and were considered by him depending on their practical significance in the field of ethics and politics.

Considering the horsemen the "support" of all classes, Cicero did not have a definite political platform. He sought first to gain the favor of the people, and then went over to the side of the optimates and recognized the union of horsemen with the nobility and the senate as the state basis.

His political activities can be characterized by the words of his brother Quintus Cicero: “Let you be sure that the Senate regards you according to how you lived before, and looks at you as a defender of his authority, Roman horsemen and rich people on the basis of your past life. they see in you a zealot of order and tranquility, but the majority, since your speeches in courts and at gatherings showed you to be half-hearted, let them think that you will act in his interests.

The first speech that has come down to us (81) “In defense of Quinctius”, about the return of illegally seized property to him, brought success to Cicero. In it, he adhered to the Asian style, in which his rival Hortensius was known. He achieved even greater success with his speech "In defense of Roscius of Ameripsky." Defending Roscius, whom his relatives accused of murdering his own father for selfish purposes, Cicero spoke out against the violence of the Sullan regime, exposing the dark actions of Sulla's favorite, Cornelius Chrysogon, with the help of which the relatives wanted to take possession of the property of the murdered. Cicero won this process and, by his opposition to the aristocracy, gained popularity among the people.

For fear of reprisals from Sulla, Cicero went to Athens and to the island of Rhodes, allegedly due to the need to study philosophy and oratory more deeply. There he listened to the rhetorician Apollonius Molon, who influenced Cicero's style. From that time on, Cicero began to adhere to the "middle" style of eloquence, which occupied the middle between the Asian and moderate Attic styles.

A brilliant education, oratorical talent, a successful start to advocacy opened Cicero access to government positions. The reaction against the aristocracy after the death of Sulla in 78 helped him in this. He took the first public position of a quaestor in Western Sicily in 76. Having earned the confidence of the Sicilians by his actions, Cicero defended their interests against the governor of Sicily, the propraetor Verres, who, using uncontrolled power, plundered the province. The speeches against Verres were of political importance, since in essence Cicero opposed the oligarchy of the optimates and defeated them, despite the fact that the judges belonged to the senatorial class and the famous Hortensius was the defender of Verres.

In 66 Cicero was elected praetor; he delivers a speech "On the Appointment of Gnaeus Pompey as General" (or "In Defense of the Law of Manilius"). Cicero supported the bill of Manilius to grant unlimited power to fight Mithridates to Gnaeus Pompey, whom he praises immoderately.

This speech, defending the interests of wealthy people and directed against the political order, was a great success. But with this speech ends Cicero's speeches against the Senate and the optimates.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party stepped up its demands for radical reforms (debt cassation, granting land to the poor). This met with clear opposition from Cicero, who in his speeches strongly opposed the agrarian bill introduced by the young tribune Rullus to purchase land in Italy and settle it with poor citizens.

When Cicero was elected consul in 63, he reinstated senators and horsemen against agrarian reforms. In the second agrarian speech, Cicero speaks sharply about the representatives of democracy, calling them troublemakers and rebels, threatening that he will make them so meek that they themselves will be surprised. Speaking against the interests of the poor, Cicero stigmatizes their leader Lucius Sergius Catiline, around whom people who suffered from the economic crisis and senatorial tyranny were grouped. Catiline, like Cicero, put forward his candidacy for consulship in 63, but, despite all the efforts of the left wing of the democratic group, to get Catiline consuls, he did not succeed due to the opposition of the optimates. Catiline conspired, the purpose of which was an armed uprising and the assassination of Cicero. The plans of the conspirators became known to Cicero thanks to well-organized espionage.

In his four speeches against Catiline, Cicero ascribes to his adversary all sorts of vices and the most vile aims, such as the desire to set fire to Rome and destroy all honest citizens.

Catiline left Rome and, with a small detachment, surrounded by government troops, died in battle near Pistoria in 62. The leaders of the radical movement were arrested and, after an illegal trial of them, were strangled in prison by order of Cicero.

Crouching before the Senate, Cicero in his speeches carries out the slogan of the union of senators and horsemen.

It goes without saying that the reactionary part of the Senate approved of Cicero's actions to suppress the Catiline conspiracy and bestowed on him the title of "father of the fatherland."

The activities of Catiline are tendentiously covered by the Roman historian Sallust. Meanwhile, Cicero himself in his speech for Murepa (XXV) cites the following remarkable statement by Catiline: “Only he who is unhappy himself can be a faithful defender of the unfortunate; but believe, afflicted and destitute, in the promises of both the prosperous and the happy... the least timid and the most affected - this is who should be called the leader and standard-bearer of the oppressed.

Cicero's brutal reprisal against the supporters of Catiline caused displeasure, popular. With the formation of the first triumvirate, which included Pompeii, Caesar and Crassus, Cicero, at the request of the people's tribune Clodius, was forced to go into exile in 58.

In 57, Cicero returned to Rome again, but no longer had his former political influence and was mainly engaged in literary work.

His speeches in defense of the people's tribune Sestius, in defense of Milop, belong to this time. At the same time, Cicero wrote the famous treatise On the Orator. As proconsul in Cilicia, Asia Minor (AD 51-50), Cicero gained popularity among the army, especially through his victory over several mountain tribes. The soldiers proclaimed him emperor (the highest military commander). Upon returning to Rome at the end of 50, Cicero joined Pompey, but after his defeat at Pharsalus (48), he refused to participate in the struggle and outwardly reconciled with Caesar. He took up the issues of oratory, publishing the treatises Orator, Brutus, and popularizing Greek philosophy in the field of practical morality.

After the assassination of Caesar by Brutus (44), Cicero again returned to the ranks of active figures, speaking on the side of the Senate party, supporting Octavian in the fight against Antony. With great harshness and passion, he wrote 14 speeches against Antony, which, in imitation of Demosthenes, are called "Philippika". For them, he was included in the proscription list and in 43 BC. e. killed.

Cicero left works on the theory and history of eloquence, philosophical treatises, 774 letters and 58 judicial and political speeches. Among them, as an expression of Cicero's views on poetry, a special place is occupied by a speech in defense of the Greek poet Archius, who appropriated Roman citizenship. Having glorified Archius as a poet, Cicero recognizes the harmonious combination of natural talent and assiduous, patient work.

The literary heritage of Cicero not only gives a clear idea of his life and work, often not always principled and full of compromises, but also paints historical pictures of the turbulent era of the civil war in Rome.

Conclusion

As can be seen from all of the above, the genre of Ancient Greek and Ancient Roman cultures did not die along with ancient civilization, but, despite the fact that the heights of this genre have so far remained inaccessible to contemporaries, it continues to live at the present time. The living word has been and remains the most important tool of Christian preaching, the ideological and political struggle of our time. And it is the rhetorical culture of antiquity that underlies the liberal education of Europe from the time of the Renaissance until the 18th century. It is no coincidence that today the surviving texts of the speeches of ancient orators are not only of historical interest, but have a powerful influence on the events of our time, retain great cultural value, being examples of convincing logic, inspired feeling and a truly creative style.

Bibliography

1. Averintsev S.S. Rhetoric and the origins of the European literary tradition. M., 1996

2. "Antique Literature", Moscow, publishing house "Enlightenment", 1986;

3. Ancient rhetoric. M., 1978. Antique theories of language and style. SPb., 1996

4. Aristotle and ancient literature. M., 1978

5. Gasparova M., V. Borukhovich "Oratory of ancient Greece", Moscow, publishing house "Fiction", 1985;

6. Kokhtev N.N. Rhetoric: Textbook for students in grades 8-9. 2nd ed. - M.: Enlightenment, 1996.

7. Losev A.F. History of ancient aesthetics. Aristotle and the Late Classic. M., 1976

8. Fundamentals of rhetoric. R.Ya. Velts, T.N. Dorozhkina, E.G. Ruzina, E.A. Yakovlev. - study guide - Ufa: kitap, 1997

9. Radtsig S.I. "History of Ancient Greek Literature", Moscow, from-in "Higher School", 1969;

10. Tronsky O.M. "History of Ancient Literature", Leningrad, UCHPEDGIZ, 1946

Hosted on Allbest.ru

...Similar Documents

social life in ancient Greece. Theory of oratory. Interest in Public Speaking in Ancient Greece. Forms of oratory, the laws of logic, the art of argument, the ability to influence the audience. Greek orators Lysias, Aristotle and Demosthenes.

presentation, added 12/05/2016

Ancient Greece and its culture occupy a special place in world history. History of Ancient Greece. Olbia: city of the Hellenistic era. Cultural History of Ancient Greece and Rome. Art of the Ancient World. Law of Ancient Greece.

abstract, added 03.12.2002

The culture of the ancient Greek Polis, the world through the eyes of ancient Greek philosophers. Man in the literature and art of Ancient Greece. In search of unearthly perfection. Features of the Hellenistic era. The rise and fall of an empire. First contacts between East and West.

abstract, added 12/02/2009

The origin of the main centers of civilization. Crete-Mycenaean, Homeric, archaic and classical periods of the economic history of Ancient Greece. Periods in the development of Ancient Rome. The economic structure of the Italian countryside. Domestic trade throughout Italy.

abstract, added 02/22/2016

The urban planning system of Ancient Greece, the improvement of cities. Monument of urban planning art of ancient Greece - the city of Miletus. Residential quarter of the Hellenistic period. The house is middle class and the people are poorer. Features of the culture of ancient Greece.

abstract, added 04/10/2014

The main line of the historical development of Greece in the VIII-VI centuries. BC. The rise of the culture of ancient Greece. The cultural heritage of Greek civilization, its influence on all the peoples of Europe, their literature, philosophy, religious thinking, political education.

abstract, added 06/17/2010

Stages of formation and development of political thought in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. The birth of the science of politics, the emergence of a realistic concept of power. The development by thinkers of antiquity of the ideas of human freedom, justice, citizenship, responsibility.

abstract, added 01/18/2011

Study of the formation, development, flourishing and decline of Ancient Greece through the prism of cultural heritage. Periods of development of Greek mythology. Periodization of ancient Greek art. Cultural ties between Greece and the East. Philosophy, architecture, literature.

abstract, added on 01/07/2015

A feature in the formation of the state in Ancient Greece was that this process, due to the constant migration of tribes, proceeded in waves, intermittently. The most interesting was the process of state formation in two Greek policies - ancient Athens and Sparta.

test, added 01/16/2009

The main periods of the history of primitive society. Reasons for the birth of the state. Civilizations of the Ancient East, Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. The era of the Middle Ages and its role in the history of mankind. The world in the era of modern times, the Thirty Years' War.

Ministry of Education of the Republic of Bashkortostan

GOU VUZ BGPU them. M. Akmulla

abstract

Topic: "Great Orators of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome"

Introduction

Chapter 1 Ancient Greek Rhetoric

1.1 Sophists-teachers of rhetoric

1.2 Socrates and Plato - the creators of the theory of "genuine eloquence"

1.3 Aristotle and his rhetoric

Chapter 2 Rhetoric of Ancient Rome

2.1 Cicero and his writings on oratory

Conclusion

Literature

Introduction

“The Word is a great ruler, who, having a very small and completely imperceptible body, does wonderful things. For it can overtake fear, and destroy sadness, and inspire joy, and awaken compassion, ”one of the most ancient philosophers-enlighteners Gorgias very aptly and figuratively noted. However, the word is not only the most important means of influencing others. It gives us the opportunity to know the world, to subjugate the forces of nature. The word is a powerful means of self-expression, this urgent need of each of the people. But how to use it? How to learn to speak in such a way as to interest listeners, influence their decisions and actions, and attract them to your side? What speech can be considered the most effective?

The answer to these and other questions related to the ability to master the word is given by rhetoric (from Greek, the art of eloquence) - the science of the skill of “persuading, captivating and delighting” with speech (Cicero).

And who is this speaker? In the "Dictionary of the Modern Russian Language" (in 17 volumes) we read the following definition of this word: 1) a person professionally engaged in the art of eloquence; 2) the person making the speech; 3) a herald of something; 4) a person with the gift of speech.

There is probably no need to convince you that every schoolchild, student who prepares messages for lessons or circle classes, speaks at school and class meetings, at solemn acts, etc., has to speak publicly. worry about your unsuccessful speeches, or get bored listening to your oratory comrades. But at the same time, of course, everyone can recall a bright, interesting, fascinating speech by a lecturer, or a favorite teacher, or one of their peers.

In order to be an excellent rhetorician, you need to know the history of rhetoric, how it began, how it developed, how ancient orators evaluated the word. This is the relevance of this topic.

Chapter 1 Ancient Greek Rhetoric

1.1 Sophists - teachers of rhetoric

Ancient Greece is considered the birthplace of eloquence, although oratory was known in Egypt, Babylon, Assyria, and India. In antiquity, the living word was of great importance: possession of it was the most important way to achieve authority in society and success in political activity. The ancient Greeks highly valued the "gift of oratory". They listened with reverence to the “sweet-talking” King Nestor of Pylos and admired Odysseus: “Speech, like a snow blizzard, rushed out of his mouth”

For a long time oratory existed only in oral form. Sample speeches, even the best ones, were not recorded. Only sophists, "teachers of wisdom", in the second half of the 5th century. BC e. introduced written recording of speeches. Sophists traveled around the cities and for a fee taught the art of arguing and "making the weakest argument the strongest." They considered it their task to teach students to "speak well and convincingly" on matters of politics and morality, for which they forced them to memorize whole speeches as role models. The main place in sophistry was occupied by the theory of persuasion. The term "sophism" was generated by the methods of evidence used by the sophists; it is also used today to determine a position, a proof that is correct in form, but false in essence. In parallel with practical eloquence, the sophists began to develop the theory of oratory - rhetoric. Tradition connects the opening of the first rhetorical schools, the creation of the first textbooks on rhetoric with the names of the sophists Korak and his student Tisias from Syracuse (5th century BC).

The sophist Gorgias of Leontina (485-380 BC) received recognition and contributed to the theory of eloquence. Gorgias paid the main attention to questions of style. To enhance the psychological impact of speech, he used stylistic means of decoration, known as "Gorgian figures". Among them are antithesis (a pronounced opposition of concepts), oxymoron (a combination of concepts that are opposite in meaning), dividing sentences into symmetrical parts, rhyming endings, alliteration (playing with consonants), assonances (repetition for the purposes of euphony and expressiveness of similar vowel sounds) . Gorgias' contemporaries - the sophists Frasimachus, Protagoras and others - continued to develop and enrich the theory of eloquence. Thanks to the work of the sophists, rhetoric received great recognition and entered the circle of sciences that are obligatory for citizens.

1.2 Socrates and Plato - the creators of the theory of "genuine eloquence"

The rhetoric of the sophists, which Plato does not consider science, he contrasts with genuine eloquence, based on knowledge of the truth, and therefore accessible only to a philosopher. This theory of eloquence is set forth in the dialogue "Phaedrus", which presents a conversation between the philosopher Socrates and the youth Phaedrus. The essence of the theory is as follows: “Before you start talking about any subject, you must clearly define this subject”

Further, according to Socrates, it is necessary to know the truth, that is, the essence of the subject: “First of all, you need to know the truth about any thing you speak or write about; be able to define everything according to this truth; true art of speech cannot be achieved without knowledge of the truth”; "He who does not know the truth, but pursues opinions, his art of speech will apparently be ridiculous and unskillful."

It is clearly and clearly stated in the dialogue about the construction of speech. In the first place, at the beginning of the speech, there should be an introduction, in the second place - a statement, in the third - evidence, in the fourth - plausible conclusions. There are also possible confirmation and additional confirmation, refutation and additional refutation, side explanation and indirect praise.

Valuable in Plato's theory of eloquence is the idea of the impact of speech on the soul. In his opinion, the speaker "needs to know how many kinds the soul has," therefore, "listeners are such and such." And what kind of speech, how it affects the soul.

So, according to Plato, true eloquence is based on knowledge of the truth. Having known the essence of things, a person comes to a correct opinion about them, and having known the nature of human souls, he has the opportunity to inspire his opinion to listeners.

1.3 Aristotle and his rhetoric

The achievements of Greek oratory were summarized and put into rules by the encyclopedist of antiquity Aristotle (384-322 BC). This he did in his Rhetoric, which consists of three books.

In the first book, the place of rhetoric among other sciences is considered, three types of speeches are reviewed: deliberative, epideictic, judicial. The purpose of these speeches is good, the categories of which are virtue, happiness, beauty and health, pleasure, wealth and friendship, honor and glory, the ability to speak and act well, natural talents, sciences, knowledge and arts, life, justice. The purpose of court speeches is to accuse or justify, they are associated with an analysis of the motives and actions of a person. Epideictic speeches are based on the concepts of beauty and shame, virtue and vice; their purpose is to praise or blame.

The second book deals with passions, morals, and general methods of proof. The orator, according to Aristotle, must emotionally influence the listeners, express anger, neglect, mercy, hostility to hatred, fear and courage, shame, beneficence, compassion, indignation.

The third book is devoted to the problems of style and construction of speech. Aristotle's doctrine of style is the doctrine of ways of expressing thoughts, of composing speech. He demanded from style, first of all, fundamental and deepest clarity: "The dignity of style lies in clarity, the proof of this is that since speech is not clear, it will not achieve its goal." The construction of speech, according to Aristotle, must correspond to the style, must be clear, simple, understandable to everyone. He called the obligatory structural parts of speech: preface, accusation and methods of its refutation, story-statement of facts, evidence, conclusion. The works of Aristotle on rhetoric had a huge impact on the entire further development of the theory of eloquence. Aristotle's rhetoric affects not only the area of oratory, it is devoted to the art of persuasive speech and dwells on ways to influence a person through speech.

Chapter 2 Speakers of Ancient Rome

2.1 Cicero and his writings on oratory

The culture of Ancient Greece, including achievements in the field of rhetoric, was creatively perceived by Ancient Rome. The heyday of Roman eloquence falls on the 1st century. n. e., when the role of the People's Assembly and the courts especially increases. The pinnacle of the development of oratory is the activity of Cicero.

Mark Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) is recognized as the brightest and most famous orator and theoretician of eloquence. His literary heritage is extensive. 58 speeches survived

Of the three main types of eloquence, Cicero presents two: political and judicial. He developed his own special style, intermediate between Asianism and moderate Atticism. His speeches are characterized by abundant, but not excessive use of rhetorical embellishments, the allocation of large, logically and linguistically distinct and rhythmically designed periods, a change - if necessary - in stylistic tone; the absence of foreign words and vulgarisms.

Cicero summarized the achievements of ancient rhetoric and his own "practical experience" in three rhetorical treatises: "On the Orator", "Brutus", "Orator". In them, he raises issues that are relevant today. First of all, he was interested in the question of what data a speaker needs, and came to the conclusion that a perfect speaker must have natural talent, memory, have skill and knowledge, be an educated person and an actor. Only with all these data, the speaker "will be able to realize the three great goals of eloquence -" convince, please, win (influence) ". Cicero, following the Greeks, continued to develop the theory of three styles and advocated the classical scheme for constructing speech, according to which the speaker must find what to say, arrange the material in order, give the proper verbal form, remember everything, pronounce.

Rhetoric- the science of eloquence. In Greece, since ancient times, beautiful, convincing and vivid speech has always been valued. Tens of years have been devoted to teaching the skill of oratory. These skills were welcomed, and people with the necessary skills were worthy of respect and reverence.

Exactly in ancient Greece the method of teaching rhetorical foundations originates. Ancient thinkers called it "the science of eloquence." Over time, the proximity of Greece to Rome and the constant rivalry between the philosophers of these states led to approximately equal opportunities for both.

What is rhetoric?

From time immemorial, this science has carried the idea of forming a person's logical thinking and his own style of presenting thoughts. The main goal is to bring information to people in a form that is understandable to them. The importance of rhetoric acquired during the period of mass trials in court, at meetings of elders. The solution of the main state problems was not complete without eloquent thinkers who, by their speeches, brought important facts to the attention of the audience, arguing their every word. Rhetorical devices are still used today by lawyers and prosecutors in their court speeches.

The origin of rhetoric is attributed to the 5th century. BC. Hellas became the birthplace of eloquence. Scientists believe that the prerequisites for a powerful impetus in the development of this science were laid by the socio-political system of this state. It is known that the cities were ruled by the most revered inhabitants of the people, and the National Assembly was the supreme body. Politicians and ordinary citizens with their questions turned to the "top" in front of hundreds of people. The courts were also significant. The accused was forced to defend himself on his own, and in many respects his life depended on the oratorical skills of the suspect.

Thinkers - the founders of rhetoric

Almost from the first years of the more or less established position of rhetoric and its popularity, teachers of eloquence (sophists) appeared in Greece. For a fee, they gave instructions and trained those who wished to receive lessons in rhetoric. From these masters, the most significant laws of oratory later spread.

The first rhetoric textbook was written in the same 5th century. BC. Only references to that work have come down to us. It was created by the Greek Corax, who at one time opened a school of eloquence in Syracuse. It is known that the publication contains the basics of the skill of oratory.

The experience of Demosthenes is remarkable. Initially, he spoke so languidly and inexpressively that the crowd always laughed at his speech. This made the future consummate speaker work on himself. He reached such heights in his skill that people listened to him, fading, and literally opening their mouths.

No less striking in his eloquence was Cicero. He became famous not only for his brilliant craftsmanship, but also for his labors. Treatises saw the light:

"Brutus".

"About the speaker".

"Speaker".

According to the idea of the thinker, only a well-educated person could become an orator. At the same time, he must fight for justice and the happiness of people. The foundations of Cicero's writings are exercises for optimal speech rhythm, work on its expressiveness, correct pronunciation, and diction. No less attention was paid to gestures and facial expressions. Speech should become simpler, but at the same time, be sublime and expressive. “The science of persuading by the skill of the word,” said Cicero about rhetoric.

When the world saw the works of Aristotle, they became relevant. This has continued at all times. They remain so to this day. Book of Aristotle so it was called - "Rhetoric". It has 3 parts: general principles (with types of texts for speeches, characteristics and arguments), names of speakers and rules for addressing people (basics of verbal formation of sentences).

The Greek Quintilian produced 12 of his works. The series of books is called Rhetorical Instructions. The scientist outlined his thoughts on the education of a master of oratory, honor, conscience and a prosperous word. Attention is also paid to the form of presentation of speech. It all starts with an introduction (attack), then the main idea (narration) is stated, after that the thought is proved (proof) and a conclusion (conclusion) is made. In the process, the author's reasoning, his conclusions can be wedged into speech. According to Quintilian, the speaker should "catch" the crowd with his speech, causing people to laugh or get angry. His speech should be clear, correct and decorated with all sorts of turns, with the correct pronunciation.

Generally, ancient Greek philosophers became the founders of the following foundations of rhetoric, which have become axioms for many years and have come down to contemporaries:

The basis of eloquence can be the natural data of a person that needs to be developed.

The right to speak is given by the education and experience of the speaker. An unlearned person cannot communicate his ideas to people. The speaker must take into account all the nuances of the topic he is talking about.

Speeches are classified. Among them there are military, judicial, business, educational.

Eloquence is based on logical thought, morality and the word.

The science of eloquence is divided into several parts. Among them: work on the content of speech, its memorization and correct pronunciation, the use of opportunities for the location of people.

Over time, the coming era of Christianity completely rejected the ideas of the ancient Greeks as pagans. But from rhetoric, the art of eloquence was adopted for a successful church service. The basics of oratory were taught in theological seminaries so that priests could prepare for communication with people, conveying to them the basic laws of God. The art of oratory also helped in sermons.

The skill of speech is valued today no less than in the days of ancient Greece. The principles of oratory help modern Greeks achieve the heights of excellence in their field and preserve the cultural traditions of the country.

Lake Plastira - Greek Switzerland.

If you are planning a trip to Greece and suddenly want to see the natural beauty of Switzerland, you do not have to go anywhere. Especially for you, fabulous Hellas took care of this and created the most beautiful lake Plastira. It is artificial and officially called Tauropos. The lake provides water to the local hydroelectric power station and the inhabitants of the city of Karditsa, not far from which it is located at an altitude of 750 meters above sea level.

Oracles in Ancient Greece

Homeric Greece

Alcoholic drinks in Greece

Traditional alcoholic drinks are an indicator by which it is easy to determine the temperament of a nation, its attitude towards alcohol and everything connected with it. In Greece, strong drinks are an integral part of any feast: both noisy fun of a big company, and a secret romantic dinner.

It should be noted that the period of the V-VI centuries. BC e. in Ancient Greece was not only a period of creation of theoretical works on rhetoric, it was also a period of outstanding orators.

First of all, as noted above, oratory was closely associated with political activity. Pericles was a famous political orator. His speeches have not been preserved. However, one can talk about his eloquence based on the reviews of his contemporaries. In particular, Pericles always prepared for speeches. When calls to speak were heard from the audience, he often refused, referring to the fact that he did not have time to prepare. During the speech, Pericles kept calm, his expression hardly changed, he did not gesticulate, never laughed and did not make the audience laugh with funny stories.

The following story of that time testifies to Pericles as an outstanding orator: the Spartan king Archidamus asked Thucydides, a representative of the aristocratic party, the political opponent of Pericles, about which of them was more skillful in the fight. Thucydides replied:

"If I knock down Pericles in the fight, then he will say that he did not fall, so he will be the winner and convince those who saw it."

The most famous ancient Greek orators were Lysias and Demosthenes. The Bald Man (c. 459-380 BCE) was forced to become an orator through the hardships of life. He delivered his first speech when he was already in his sixties. As a result of the oligarchic coup (404 BC. E. E.), Lysias went bankrupt and was forced to act as an accuser at the trial against the culprit in the death of his brother. Then he chose the profession of a logographer. Logograph- this is the person who created speeches for others.

Among the advantages of Lysias, one should note his ability to prepare material in a fairly short time, established by the Athenian court. His speeches were distinguished by brevity and clarity of thought. This was ensured by the desire to use words in their own sense, to avoid bold metaphors, poetic expressions and the like. Later, the style of Lysias was recognized as a model for Atticism and became an example to follow.

The most interesting orator of ancient Greece was probably Demosthenes (384-322 BC). His figure, in particular, shows that for the success of a speaker, natural inclinations are not the main ones. The main thing is the constant training of both thoughts and words. From childhood, Demosthenes had a weak voice and lisped. These shortcomings, as well as the indecision with which he kept himself in public, led to the failure of his first performances. However, he was a very stubborn man: he overcame his physical handicaps with constant exercise. Demosthenes tried to correct his inexpressive pronunciation by picking up pebbles in his mouth and trying to read passages from poems clearly and legibly. The weak voice improved by the fact that he went to the seashore and tried to drown out the noise of the coastal waves with the sound of his voice.

A well-known speaker believed that tone and manner of pronunciation provide persuasiveness to words. In this regard, Plutarch in the biography of Demosthenes recalls such an incident. Once a Greek asked Demosthenes to appear in court and defend him, because he was beaten:

"But you didn't get hurt by that!" - The speaker told him. "Nothing hurt!" - exclaimed the Greek at the top of his voice. "Now," said Demosthenes, "I really hear the person who has suffered."

In addition, Demosthenes carefully studied the speeches that he heard and tried to restore the course of reasoning from memory. To his own words or the words of other people, he came up with possible corrections and ways to express the same thoughts in other words. He never performed without prior preparation. Demosthenes himself admitted that although he did not write the whole speech in full, he did not speak at all without preliminary outlines. At the same time, he said that the one who prepares the speech in advance is truly devoted to the people, that this is the service to him. In Demosthenes' opinion, to show indifference before the majority of the audience understands the speech means to sympathize with the oligarchy and rely more on coercion than persuasion.

This constant preliminary preparation for speeches once again shows that not only natural talent is important for oratory skills, but also hard work. Demosthenes eventually overcame his physical handicaps.

The speeches of Demosthenes against the Macedonian king Philip are well known. According to legend, Philip of Macedon himself, when he read one of them, remarked: "If I had heard Demosthenes, I myself would have voted for him as a leader in the fight against me."

ORATORY

The Hellenes demonstrated their abilities and civil position primarily in public life. One of the brightest manifestations of the culture of ancient Greece was oratory. Its rise is associated with the conditions of life in the policy, when any information was transmitted orally. The need to defend one's views and convince fellow citizens of one's rightness in debates in a national assembly, jury trial, etc. unusually elevated the art of owning a sounding word.

Analyzing the art of eloquence, Aristotle divided all speeches into three types: advisory, or political judicial(accusatory and defensive) and epideictic, or solemn. The purpose of deliberative speeches is to persuade or reject, judicial speeches to accuse or justify, epideictic speeches to praise or blame.

The huge role of the sounding word in the life of the ancient Greeks caused the need for rhetoricians- teachers of eloquence. So it appears rhetoric- oratory, and mastery of rhetoric becomes the highest level of ancient education.

A famous philosopher and teacher of eloquence was Gorgias(c. 480 - c. 380 BC) from the Sicilian city of Leontina. When he in 427 BC. e. arrived in Athens, he was enthusiastically received as an orator and teacher of rhetoric. Gorgias spoke to the Athenians with defensive speeches on mythological subjects. Two of them have come down to us: “Praise to Helen” and “Justification of Palamedes”, in which Gorgias convincingly, with brilliant argumentation, proved the innocence of mythological characters. Among the speeches of Gorgias there are many examples of solemn eloquence. For example, in the "Tombstone" the orator glorifies the Greeks who died in defense of the fatherland in a stilted style.

To increase the psychological impact on listeners, Gorgias was the first to use poetic techniques in oratory speech: antithesis, metaphors and comparisons, rhythmic articulation of speech, and even rhymed endings (they were called Gorgias figures). Gorgias taught not only the design of the material, but also the principles of its presentation: "Refut the serious arguments of the enemy with a joke, jokes with seriousness." The rhetorician, who had many students and followers, outlined his theory of oratory in special writings. He had a great influence on the orators Lysias and Isocrates, on the historian Thucydides. The philosopher Plato in the dialogue "Gorgias" analyzes in detail the skill of the famous orator.

The most common oratorical genre in ancient Greece was court speeches. In the life of the Hellenes, and especially the Athenians, who were famous for their litigation, the court occupied a very large place. In order to decide cases in court, a citizen had to not only know the laws, but also be able to attract the sympathy of jurors to his side. The connoisseur of rhetoric, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, taught: “When judges and accusers are the same person, it is necessary to shed abundant tears and utter thousands of complaints in order to be listened to with benevolence.” It was not for everyone to make a convincing and vivid speech. These circumstances have led to logographers– experienced litigant speech writers. There have been cases when the same logographer made speeches for both the plaintiff and the defendant.

The famous logographer and master of judicial eloquence Lysias (c. 435-380 BC) came from a family of meteca. He received his rhetorical education in the southern Italian city of Furii from famous sophists. Returning to Athens as a metecus, he devoted himself entirely to the activity of a logographer and wrote more than 230 speeches (of which about 30 have been preserved in their entirety and in fragments). The oratorical style of Lysias is characterized by persuasiveness in presenting the circumstances of the case. He recounts events simply, concisely and expressively. Describing the character of a person, Lysias endows him with a language adequate to his status. Perhaps his skill was most fully manifested in the speech “Against Eratosthenes”, where the speaker managed to draw a vivid picture of the atrocities of the Athenian tyrants, who, hiding behind lofty phrases, indulged in robberies and murders. And in the famous speech of Lysias in defense of the disabled, with great artistic skill, a portrait of an elderly Athenian citizen who received disability benefits from the state was painted with great artistic skill. With his speeches, Lysias laid the foundations of European judicial eloquence.

One of the famous students of Gorgias was Isocrates (436-338 BC), who became an unsurpassed master solemn eloquence. Because of his shyness and weak voice, Isocrates was first a logographer, then he founded a school of rhetoric in Athens, which became famous throughout Greece. 21 of his speeches have come down to us, the most famous of which are Panegyric, Philip, Panathenaic Speech, as well as a eulogy to the Cypriot king Evagoras. Isocrates lived in the era of the crisis of the polis system and in his speeches tried to formulate a political program for the salvation of Hellas by uniting all the Greeks for a joint campaign against the barbarians. He proposed to transfer the wars that had engulfed Greece to Asia, the wealth of Asia to Europe, and the union of Greek policies to be placed under the rule of the monarch of a rich and strong state (he considered Philip II, king of ancient Macedonia, to be the most suitable figure for this role).

The school of Isocrates developed principles of construction of the speaker's speech. It should include an introduction to grab the attention of the listeners, a body with a compelling and vivid system of evidence, a refutation of the opponent's arguments, and finally a conclusion summarizing what has been said. The speaker's style is characterized by numerous speech embellishments. The speeches of Isocrates are distinguished by the rhythmic articulation of speech, the smoothness of presentation, the use of refined rhetorical devices, etc. The orator strove for the prose speech to sound as elegant and harmonious as the poetic one. According to his contemporaries, his speeches were focused more on the reader than on the listener. The rhetorical art of Isocrates and his ideas of the unity of the Greek world had a huge impact on his contemporaries and were further developed in the Hellenistic era.

The greatest orator of antiquity, the master political eloquence was Demosthenes (c. 384-322 BC). He was born into the family of a wealthy Athenian citizen, but after the death of his father, the guardians took possession of the orphan's property by fraud. With a weak voice and poor diction, the young man seemed to have no chance of succeeding in rhetoric. But with hard work, he managed to overcome his shortcomings and become a brilliant speaker. For contemporaries and descendants, Demosthenes appears as a patriot of Athens, an ideological leader in the struggle for Hellas to preserve its independence.

Most of the speeches of Demosthenes (61 speeches, 56 introductions to speeches and 6 letters are attributed to the orator) are devoted to current political issues worried the Athenian citizens. Therefore, unlike the texts of Isocrates, designed for recitation to a small group of listeners, the passionate speeches of Demosthenes were focused on mass audience. The political position of the orator is most clearly revealed in the so-called "Philippics" (eight speeches: three "Olynthian", three "Against Philip", "On the World", "On Affairs in Chersonese"), united by a single theme of the struggle against the Macedonian king Philip II. In them, Demosthenes called on fellow citizens to create a Hellenic coalition against the Macedonian danger.

In his speeches there are no detailed long introductions, the speaker quickly moves on to the main topic. To win the audience over to his side, Demosthenes speaks in short phrases, dynamic and tense, using both high style and colloquial speech. The speaker skillfully introduces both imaginary dialogues with opponents, and rhetorical questions, and antitheses, and metaphors, and “default figures”, inviting listeners to draw their own conclusions. An outstanding master of public eloquence of the classical era, Demosthenes became a model for many outstanding orators of antiquity.

From the book Ancient Rus' and the Great Steppe author Gumilyov Lev Nikolaevich35. Where is the art? Indeed, why is there nothing left of the Khazars, while the Xiongnu kurgans are full of masterpieces, Turkic and Polovtsian “stone women” were found in huge numbers, Uighur frescoes adorn the galleries of the Hermitage and the Berlin Museum, and even from ancient

From the book History of Art of All Times and Peoples. Volume 2 [European Art of the Middle Ages] author Woerman Karl From the book Empire of Charlemagne and the Arab Caliphate. End of the ancient world author Pirenne Henri3. Art The Germanic invasions did not disturb in any sensitive way the development of art in the Mediterranean. In art, the influence of the East not only survived, but became more and more dominant. Influence of the cultural traditions of Persia, Syria and Egypt

author Kumanetsky KazimierzOratory The zeal of the sophists, their desire to instill in young people the skills of skillful dispute, reasoned debate on any topic, gave rise to a steady interest of the Greeks and, above all, the inhabitants of democratic Athens, in judicial speeches. Gained great popularity

From the book History of Culture of Ancient Greece and Rome author Kumanetsky KazimierzORATORY After the loss of independence by Greece, the art of eloquence, not finding a use in political life, seemed to come to naught. But this did not happen. Displaced from the ago. ry, from the political sphere, it found refuge in the schools of rhetoric.

From the book History of Culture of Ancient Greece and Rome author Kumanetsky KazimierzORATORY The aggravation of the political struggle and the example of the Greeks prompted the active participants in the events to be more concerned about the publication of their political and judicial speeches. If in the III century. BC e. Appius Claudius, and in the first half of the 11th century. BC e. Cato the Elder was composed in

author Yarov Sergey Viktorovich4. Art Domestic filmmakers of the 1920s. made an outstanding contribution to the development of not only Soviet, but also world cinema. The films “October”, “Battleship Potemkin”, “Strike” by S. Eisenstein, “Mother” by V. Pudovkin, “Arsenal” and

From the book Russia in 1917-2000. A book for everyone interested in national history author Yarov Sergey Viktorovich4. Art A caustic satire on "Soviet" morals (true, attributing negative phenomena to "remnants of the past"), a realistic view of the problems of history and modern life, subtle lyricism - all this was reflected with great force in the cinema art of the 1950s-1960s

From the book Russia in 1917-2000. A book for everyone interested in national history author Yarov Sergey Viktorovich4. Art Despite the strict censorship conditions, it is impossible to talk about the forceful and artistic unification of the spheres of art in the 1960s–1980s. is no longer possible. The policy of direct and strict prohibitions has begun to become a thing of the past. However, they did not completely abandon it: they ended up on the notorious

From the book Russia in 1917-2000. A book for everyone interested in national history author Yarov Sergey Viktorovich4. Art Filmmakers were the first among those who contributed to the cause of the spiritual "restructuring" of society. The film "Repentance" by T. Abuladze exposed the arbitrariness of the 1930s. Many paintings were devoted to a satirical description of the mores of the bureaucracy. Public response

From the book Russia in 1917-2000. A book for everyone interested in national history author Yarov Sergey Viktorovich4. Art Among the most notable films of the 1990s are Urga and Burnt by the Sun by N. Mikhalkov, The Government Inspector by A. Gazarov, Brother by A. Balabanov, Sky in Diamonds by V. Pichula, Shirley myrli" by V. Menshov, "Country of the Deaf" by V. Todorovsky. New actors received recognition

From the book History of the Ancient World [East, Greece, Rome] author Nemirovsky Alexander ArkadievichOratory It is very significant that at the turn of the 5th and 4th centuries BC. e., during the period of clearly identified trends in the beginning of the crisis of the polis system, another genre of Hellenic literature appeared - the works of orators, masters of eloquence and rhetoric. At that time,

From the book The Art of Ancient Greece and Rome: a teaching aid author Petrakova Anna EvgenievnaTopic 21 Fine Arts of Republican Rome (sculpture, painting, arts and crafts) era (slow development in

author Petrakova Anna EvgenievnaTopic 15 Architecture and fine arts of the Old and Middle Babylonian periods. Architecture and fine arts of Syria, Phenicia, Palestine in the II millennium BC. e Chronological framework of the Old and Middle Babylonian periods, the rise of Babylon during

From the book Art of the Ancient East: study guide author Petrakova Anna EvgenievnaTopic 16 Architecture and visual arts of the Hittites and Hurrians. Architecture and art of Northern Mesopotamia at the end of II - beginning of I millennium BC. e Features of Hittite architecture, types of structures, construction equipment. Hatussa architecture and issues

From the book Art of the Ancient East: study guide author Petrakova Anna EvgenievnaTopic 19 Architecture and fine arts of Persia in the 1st millennium BC. e.: architecture and art of Achaemenid Iran (559-330 BC) General characteristics of the political and economic situation in Iran in the 1st millennium BC. e., the rise to power of Cyrus from the Achaemenid dynasty in

Oratory as a prototype of journalism

Oratory as a prototype of journalism Quotes about Napoleon - dslinkov — LiveJournal

Quotes about Napoleon - dslinkov — LiveJournal Me vengeance The man on the bulldozer destroyed the city

Me vengeance The man on the bulldozer destroyed the city