Mongol Tatar invasion of Rus' map. Rise of the Mongol-Tatar Empire

Steppe ubermensch on a tireless Mongolian horse (Mongolia, 1911)

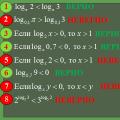

The historiography about the invasion of the Mongol-Tatars (or Tatar-Mongols, or Tatars and Mongols, and so on, as you like) into Rus' goes back over 300 years. This invasion has become a generally accepted fact since the end of the 17th century, when one of the founders of Russian Orthodoxy, the German Innocent Gisel, wrote the first textbook on the history of Russia - “Synopsis”. According to this book, the Russians hammered home history for the next 150 years. However, so far no historian has taken it upon himself to make a “road map” of Batu Khan’s campaign in the winter of 1237-1238 in North-Eastern Rus'.

A little background

IN late XII century, a new leader appeared among the Mongol tribes - Temujin, who managed to unite most of them around himself. In 1206, he was proclaimed at the kurultai (analogous to the Congress of People's Deputies of the USSR) as the all-Mongolian khan under the nickname Genghis Khan, who created the notorious “state of nomads.” Without wasting a minute, the Mongols began to conquer the surrounding territories. By 1223, when the Mongol detachment of commanders Jebe and Subudai clashed with the Russian-Polovtsian army on the Kalka River, the zealous nomads managed to conquer territories from Manchuria in the east to Iran, the southern Caucasus and modern western Kazakhstan, defeating the state of Khorezmshah and capturing part of northern China along the way.

In 1227, Genghis Khan died, but his heirs continued his conquests. By 1232, the Mongols reached the middle Volga, where they waged war with the nomadic Cumans and their allies - the Volga Bulgars (ancestors of the modern Volga Tatars). In 1235 (according to other sources - in 1236), a decision was made at the kurultai on a global campaign against the Kipchaks, Bulgars and Russians, as well as further to the West. The grandson of Genghis Khan, Khan Batu (Batu), had to lead this campaign. Here we need to make a digression. In 1236-1237, the Mongols, who by that time were fighting in vast areas from modern Ossetia (against the Alans) to the modern Volga republics, captured Tatarstan (Volga Bulgaria) and in the fall of 1237 began concentrating for a campaign against the Russian principalities.

Empire on a planetary scale

Empire on a planetary scale

In general, why the nomads from the banks of Kerulen and Onon needed to conquer Ryazan or Hungary is not really known. All attempts by historians to laboriously justify such agility of the Mongols look rather pale. Regarding Western campaign Mongols (1235-1243), they came up with the story that the attack on the Russian principalities was a measure to secure their flank and destroy potential allies of their main enemies - the Cumans (part of the Cumans went to Hungary, but the bulk of them became the ancestors of modern Kazakhs). True, neither the Ryazan principality, nor the Vladimir-Suzdal, nor the so-called. The “Novgorod Republic” was never allies of either the Cumans or the Volga Bulgars (you can read an interesting study on this topic).

Also, almost all historiography about the Mongols does not really say anything about the principles of forming their armies, the principles of managing them, and so on. At the same time, it was believed that the Mongols formed their tumens (field operational units), including from conquered peoples, the soldier was not paid anything for his service, and for any offense they were threatened with the death penalty.

Scientists tried to explain the successes of the nomads this way and that, but each time it turned out quite funny. Although, ultimately, the level of organization of the Mongol army - from intelligence to communications - could be envied by the armies of the most developed states of the 20th century (however, after the end of the era of wonderful campaigns, the Mongols - already 30 years after the death of Genghis Khan - instantly lost all their skills). For example, it is believed that the head of Mongolian intelligence, commander Subudai, maintained relations with the Pope, the German-Roman emperor, Venice, and so on.

Moreover, the Mongols, naturally, during their military campaigns acted without any radio communications, railways, road transport and so on. IN Soviet time historians interspersed the traditional by that time fantasy about steppe ubermenches who did not know fatigue, hunger, fear, etc., with classical ritual in the field of the class-formational approach:

With a general recruitment into the army, each ten tents had to field from one to three warriors, depending on the need, and provide them with food. Weapons in Peaceful time stored in special warehouses. It was the property of the state and was issued to soldiers when they went on a campaign. Upon returning from the campaign, each warrior was obliged to surrender his weapons. The soldiers did not receive a salary, but they themselves paid the tax with horses or other livestock (one head per hundred heads). In war, each warrior had an equal right to use the spoils, a certain part of which was obliged to hand over to the khan. In the periods between campaigns, the army was sent to public works. One day a week was reserved for serving the khan.

The organization of the army was based on the decimal system. The army was divided into tens, hundreds, thousands and tens of thousands (tumyns or darkness), headed by foremen, centurions and thousands. The commanders had separate tents and a reserve of horses and weapons.

The main branch of the army was cavalry, which was divided into heavy and light. The heavy cavalry fought with the main forces of the enemy. The light cavalry carried out guard duty and conducted reconnaissance. She started a battle, disrupting the enemy ranks with arrows. The Mongols were excellent archers from horseback. Light cavalry pursued the enemy. The cavalry had a large number of factory (spare) horses, which allowed the Mongols to move very quickly over long distances. A feature of the Mongol army was the complete absence of a wheeled train. Only the tents of the khan and especially noble persons were transported on carts...

Each warrior had a file for sharpening arrows, an awl, a needle, thread and a sieve for sifting flour or straining muddy water. The rider had a small tent, two tursuks (leather bags): one for water, the other for kruta (dried sour cheese). If food supplies ran low, the Mongols bled their horses and drank it. In this way they could be content for up to 10 days.

In general, the term “Mongol-Tatars” (or Tatar-Mongols) itself is very bad. It sounds something like Croatian-Indians or Finno-Negros, if we talk about its meaning. The fact is that Russians and Poles, who encountered nomads in the 15th-17th centuries, called them the same - Tatars. Subsequently, the Russians often transferred this to other peoples who had nothing to do with the nomadic Turks in the Black Sea steppes. Europeans also made their contribution to this mess, who for a long time considered Russia (then Muscovy) Tatarstan (more precisely, Tartaria), which led to very bizarre constructions.

The French view of Russia in the mid-18th century

The French view of Russia in the mid-18th century

One way or another, society learned that the “Tatars” who attacked Rus' and Europe were also Mongols only at the beginning of the 19th century, when Christian Kruse published “Atlas and tables for reviewing the history of all European lands and states from their first population to our times." Then Russian historians happily picked up the idiotic term.

Particular attention should also be paid to the issue of the number of conquerors. Naturally, no documentary data on the size of the Mongol army has reached us, and the most ancient source that enjoys unquestioning trust among historians is historical work a team of authors under the leadership of the official of the Iranian state of the Hulaguids, Rashid ad-Din, “List of Chronicles”. It is believed that it was written in early XIV century in Persian, however, it surfaced only at the beginning of the 19th century, the first partial edition in French published in 1836. Until the middle of the 20th century, this source was not completely translated and published.

According to Rashid ad-Din, by 1227 (the year of Genghis Khan's death), the total army of the Mongol Empire was 129 thousand people. If you believe Plano Carpini, then 10 years later the army of phenomenal nomads consisted of 150 thousand Mongols themselves and another 450 thousand people recruited in a “voluntary-forced” manner from subject peoples. Pre-revolutionary Russian historians estimated the size of Batu's army, concentrated in the fall of 1237 near the borders of the Ryazan principality, from 300 to 600 thousand people. At the same time, it was taken for granted that each nomad had 2-3 horses.

By the standards of the Middle Ages, such armies look completely monstrous and implausible, we must admit. However, reproaching pundits for fantasizing is too cruel for them. It is unlikely that any of them could even imagine even a couple of tens of thousands of mounted warriors with 50-60 thousand horses, not to mention the obvious problems with managing such a mass of people and providing them with food. Since history is an inexact science, and indeed not a science at all, everyone can evaluate the range of fantasy researchers. We will use the now classic estimate of the size of Batu’s army at 130-140 thousand people, which was proposed by the Soviet scientist V.V. Kargalov. His assessment (like all the others, completely sucked from thin air, to be very serious) in historiography, however, is prevalent. In particular, it is shared by the largest modern Russian researcher of the history of the Mongol Empire, R.P. Khrapachevsky.

From Ryazan to Vladimir

In the autumn of 1237, Mongol troops, who had fought throughout the spring and summer across vast areas from the North Caucasus, Lower Don and to the middle Volga region, converged general collection- Onuza River. It is believed that we're talking about O modern river Prices in the modern Tambov region. Probably, some detachments of Mongols also gathered in the upper reaches of the Voronezh and Don rivers. There is no exact date for the start of the Mongols’ offensive against the Ryazan principality, but it can be assumed that it took place in any case no later than December 1, 1237. That is, steppe nomads with a herd of almost half a million horses, they decided to go on a hike in winter. This is important for our reconstruction. If so, then they probably had to be sure that in the forests of the Volga-Osk interfluve, still rather weakly colonized by the Russians by that time, they would have enough food for horses and people.

Along the valleys of the Lesnoy and Polny Voronezh rivers, as well as the tributaries of the Pronya River, the Mongol army, moving in one or several columns, passes through the forested watershed of the Oka and Don. The embassy of the Ryazan prince Fyodor Yuryevich arrives to them, which turned out to be ineffective (the prince is killed), and somewhere in the same region the Mongols meet the Ryazan army in a field. In a fierce battle, they destroy it, and then move upstream of the Pronya, plundering and destroying small Ryazan cities - Izheslavets, Belgorod, Pronsk, and burning Mordovian and Russian villages.

Here we need to make a small clarification: we do not have accurate data on the number of people in the then North-Eastern Rus', but if we follow the reconstruction of modern scientists and archaeologists (V.P. Darkevich, M.N. Tikhomirov, A.V. Kuza), then it was not large and, in addition, it was characterized by low population density. Eg, The largest city Ryazan land - Ryazan, maximum 6-8 thousand people, another 10-14 thousand people could live in the agricultural district of the city (within a radius of 20-30 kilometers). The remaining cities had a population of several hundred people, at best, like Murom - up to a couple of thousand. Based on this, it is unlikely that the total population of the Ryazan principality could exceed 200-250 thousand people.

Of course, for the conquest of such a “proto-state” 120-140 thousand soldiers were more than an excessive number, but we will stick to the classical version.

On December 16, the Mongols, after a march of 350-400 kilometers (that is, the pace of the average daily march here is up to 18-20 kilometers), go to Ryazan and begin its siege - they build a wooden fence around the city, build stone-throwing machines, with the help of which they lead shelling of the city. In general, historians admit that the Mongols achieved incredible - by the standards of that time - success in siege warfare. For example, historian R.P. Khrapachevsky seriously believes that the Mongols were able to build any stone-throwing machines on the spot from available wood in literally a day or two:

There was everything necessary to assemble stone throwers - the united army of the Mongols had enough specialists from China and Tangut..., and Russian forests abundantly supplied the Mongols with wood for assembling siege weapons.

Finally, on December 21, Ryazan fell after a fierce assault. True, an inconvenient question arises: we know that the total length of the city’s defensive fortifications was less than 4 kilometers. Most of the Ryazan soldiers died in the border battle, so it is unlikely that there were many soldiers in the city. Why did a gigantic Mongol army of 140 thousand soldiers sit for 6 whole days under its walls if the balance of forces was at least 100-150:1?

We also do not have any clear evidence of what the climatic conditions were in December 1238, but since the Mongols chose the ice of rivers as a method of transportation (there was no other way to pass through wooded areas, the first permanent roads in North-Eastern Rus' are documented only in the 14th century). century, all Russian researchers agree with this version), we can assume that it was already a normal winter with frosts, possibly snow.

An important question is also what the Mongolian horses ate during this campaign. From the works of historians and modern research steppe horses, it is clear that we were talking about very unpretentious, small - height at the withers up to 110-120 centimeters, conics. Their main diet is hay and grass (they did not eat grain). In their natural habitat, they are unpretentious and quite hardy, and in winter, during tebenevka, they are able to tear up snow in the steppe and eat last year’s grass.

Based on this, historians unanimously believe that thanks to these properties, the question of feeding the horses during the campaign in the winter of 1237-1238 against Rus' did not arise. Meanwhile, it is not difficult to notice that the conditions in this region (the thickness of the snow cover, the area of grass stands, as well as the general quality of phytocenoses) differ from, say, Khalkha or Turkestan. In addition, the winter training of steppe horses consists of the following: a herd of horses slowly, walking a few hundred meters a day, moves across the steppe, looking for withered grass under the snow. Animals thus save their energy costs. However, during the campaign against Rus', these horses had to walk 10-20-30 or even more kilometers a day in the cold (see below), carrying luggage or a warrior. Were horses able to replenish their energy expenditure under such conditions? More interest Ask: if Mongolian horses dug through snow and found grass under it, then what should be the area of their daily feeding grounds?

After the capture of Ryazan, the Mongols began to advance towards the Kolomna fortress, which was a kind of “gate” to the Vladimir-Suzdal land. Having walked 130 kilometers from Ryazan to Kolomna, according to Rashid ad-Din and R.P. Khrapachevsky, the Mongols were “stuck” at this fortress until January 5 or even 10, 1238 - that is, at least for almost 15-20 days. On the other hand, a strong Vladimir army is moving towards Kolomna, which Grand Duke Yuri Vsevolodovich probably equipped immediately after receiving news of the fall of Ryazan (he and the Chernigov prince refused to help Ryazan). The Mongols send an embassy to him with an offer to become their tributary, but the negotiations also turn out to be fruitless (according to the Laurentian Chronicle, the prince still agrees to pay tribute, but still sends troops to Kolomna. It is difficult to explain the logic of such an act).

According to V.V. Kargalov and R.P. Khrapachevsky, the battle of Kolomna began no later than January 9 and lasted for 5 whole days (according to Rashid ad-Din). Here another logical question immediately arises - historians are sure that the military forces of the Russian principalities as a whole were modest and corresponded to the reconstructions of that era, when an army of 1-2 thousand people was standard, and 4-5 thousand or more people seemed like a huge army. It is unlikely that the Vladimir prince Yuri Vsevolodovich could have collected more (if we make a digression: the total population of the Vladimir land, according to various estimates, varied between 400-800 thousand people, but they were all scattered over a vast territory, and the population of the capital city of the earth - Vladimir, even according to the most daring reconstructions, it did not exceed 15-25 thousand people). However, near Kolomna the Mongols were pinned down for several days, and the intensity of the battle is shown by the fact of the death of Genghisid Kulkan, the son of Genghis Khan. With whom did the gigantic army of 140 thousand nomads fight so fiercely? With several thousand Vladimir soldiers?

After the victory at Kolomna in either a three- or five-day battle, the Mongols are vigorously moving along the ice of the Moscow River towards the future Russian capital. They cover a distance of 100 kilometers in literally 3-4 days (the pace of an average daily march is 25-30 kilometers): according to R.P. Khrapachevsky, the nomads began the siege of Moscow on January 15 (according to N.M. Karamzin - January 20). The nimble Mongols took the Muscovites by surprise - they did not even know about the results of the battle of Kolomna, and after a five-day siege, Moscow shared the fate of Ryazan: the city was burned, all its inhabitants were exterminated or taken prisoner.

Again, Moscow at that time, if we take archaeological data as the basis for our reasoning, was an absolutely tiny town. Thus, the first fortifications, built back in 1156, had a length of less than 1 kilometer, and the area of the fortress itself did not exceed 3 hectares. By 1237, it is believed that the area of the fortifications had already reached 10-12 hectares (that is, approximately half the territory of the current Kremlin). The city had its own suburb - it was located on the territory of modern Red Square. The total population of such a city hardly exceeded 1000 people. What a huge army of Mongols, possessing supposedly unique siege technologies, did for five whole days in front of this insignificant fortress, one can only guess.

It is also worth noting here that all historians recognize the fact of the movement of the Mongol-Tatars without a convoy. They say that the unpretentious nomads did not need it. Then it remains not entirely clear how and on what the Mongols moved their stone-throwing machines, shells for them, forges (for repairing weapons, replenishing lost arrowheads, etc.), and how they drove away prisoners. Because all the time archaeological excavations Not a single burial of “Mongol-Tatars” was found on the territory of North-Eastern Rus'; some historians even agreed on the version that the nomads took their dead back to the steppes (V.P. Darkevich, V.V. Kargalov). Of course, it’s not even worth raising the question of the fate of the wounded or sick in this light (otherwise our historians will come up with the fact that they were eaten, a joke) ...

However, after spending about a week in the vicinity of Moscow and plundering its agricultural contado (the main agricultural crop in this region was rye and partly oats, but steppe horses accepted grain very poorly), the Mongols moved along the ice of the Klyazma River (crossing the forest watershed between this river and Moscow River) to Vladimir. Having covered over 140 kilometers in 7 days (the pace of an average daily march is about 20 kilometers), on February 2, 1238, the nomads began the siege of the capital of the Vladimir land. By the way, it is at this crossing Mongol army 120-140 thousand people are “caught” by a tiny detachment of the Ryazan boyar Evpatiy Kolovrat of either 700 or 1700 people, against whom the Mongols - out of powerlessness - are forced to use stone-throwing machines in order to defeat him (it is worth considering that the legend about Kolovrat was It was recorded, according to historians, only in the 15th century, so... it is difficult to consider it completely documentary).

Let’s ask an academic question: what is an army of 120-140 thousand people with almost 400 thousand horses (and it’s not clear if there is a convoy?) moving on the ice of some Oka or Moscow river? The simplest calculations show that even moving with a front of 2 kilometers (in reality, the width of these rivers is significantly less), such an army under the most ideal conditions (everyone moves at the same speed, maintaining a minimum distance of 10 meters) stretches for at least 20 kilometers. If we take into account that the width of the Oka is only 150-200 meters, then the giant army of Batu stretches for almost... 200 kilometers! Again, if everyone walks at the same speed, maintaining a minimum distance. And on the ice of the Moscow or Klyazma rivers, the width of which varies from 50 to 100 meters at best? For 400-800 kilometers?

It is interesting that none of the Russian scientists over the past 200 years have even asked such a question, seriously believing that giant cavalry armies literally fly through the air.

In general, at the first stage of Batu Khan’s invasion of North-Eastern Rus' - from December 1, 1237 to February 2, 1238, a conventional Mongolian horse covered about 750 kilometers, which gives an average daily rate of movement of 12 kilometers. But if we exclude from the calculations at least 15 days of standing in the Oka floodplain (after the capture of Ryazan on December 21 and the battle of Kolomna), as well as a week of rest and looting near Moscow, the pace of the average daily march of the Mongol cavalry will seriously improve - up to 17 kilometers per day.

It cannot be said that these are some kind of record paces of march (the Russian army during the war with Napoleon, for example, made 30-40-kilometer daily marches), the interesting thing here is that all this happened in the dead of winter, and such paces were maintained for quite a long time.

From Vladimir to Kozelsk

On the fronts of the Great Patriotic War XIII century

On the fronts of the Great Patriotic War XIII century

Prince Yuri Vsevolodovich of Vladimir, having learned about the approach of the Mongols, left Vladimir, leaving with a small squad for the Trans-Volga region - there, among the windbreaks on the Sit River, he set up a camp and awaited the arrival of reinforcements from his brothers - Yaroslav (father of Alexander Nevsky) and Svyatoslav Vsevolodovich. There were very few warriors left in the city, led by Yuri's sons - Vsevolod and Mstislav. Despite this, the Mongols spent 5 days with the city, shelling it with stone throwers, taking it only after the assault on February 7th. But before this, a small detachment of nomads led by Subudai managed to burn Suzdal.

After the capture of Vladimir, the Mongol army is divided into three parts. The first and largest unit under the command of Batu goes from Vladimir to the northwest through the impassable forests of the Klyazma and Volga watershed. The first march is from Vladimir to Yuryev-Polsky (about 60-65 kilometers). Then the army is divided - part goes exactly northwest to Pereyaslavl-Zalessky (about 60 kilometers), and after a five-day siege this city fell. What was Pereyaslavl like then? It was a relatively small city, slightly larger than Moscow, although it had defensive fortifications up to 2.5 kilometers long. But its population also hardly exceeded 1-2 thousand people.

Then the Mongols go to Ksnyatin (about another 100 kilometers), to Kashin (30 kilometers), then turn west and move along the ice of the Volga to Tver (from Ksnyatin in a straight line it’s a little more than 110 kilometers, but they go along the Volga, there it’s all 250- 300 kilometers).

The second part goes through the dense forests of the Volga, Oka and Klyazma watershed from Yuryev-Polsky to Dmitrov (about 170 kilometers in a straight line), then after its capture - to Volok-Lamsky (130-140 kilometers), from there to Tver (about 120 kilometers) , after the capture of Tver - to Torzhok (together with the detachments of the first part) - in a straight line it is about 60 kilometers, but, apparently, they walked along the river, so it will be at least 100 kilometers. The Mongols reached Torzhok on February 21 - 14 days after leaving Vladimir.

Thus, the first part of the Batu detachment travels at least 500-550 kilometers in 15 days through dense forests and along the Volga. True, from here you need to throw out several days of siege of cities and it turns out about 10 days of march. For each of which, nomads pass through forests 50-55 kilometers a day! The second part of his detachment covers a total distance of less than 600 kilometers, which gives an average daily march pace of up to 40 kilometers. Taking into account a couple of days for sieges of cities - up to 50 kilometers per day.

Near Torzhok, a rather modest city by the standards of that time, the Mongols were stuck for at least 12 days and took it only on March 5 (V.V. Kargalov). After the capture of Torzhok, one of the Mongol detachments advanced towards Novgorod another 150 kilometers, but then turned back.

The second detachment of the Mongol army under the command of Kadan and Buri left Vladimir to the east, moving along the ice of the Klyazma River. Having walked 120 kilometers to Starodub, the Mongols burned this city, and then “cut off” the forested watershed between the lower Oka and middle Volga, reaching Gorodets (this is about another 170-180 kilometers, if the crow flies). Further, the Mongolian troops along the ice of the Volga reached Kostoroma (this is another 350-400 kilometers), separate units even reached Galich Mersky. From Kostroma, the Mongols of Buri and Kadan went to join the third detachment under the command of Burundai to the west - to Uglich. Most likely, the nomads moved on the ice of the rivers (in any case, let us remind you once again, this is the custom in Russian historiography), which gives about another 300-330 kilometers of travel.

In early March, Kadan and Buri were already near Uglich, having covered a little over three weeks to 1000-1100 kilometers. The average daily pace of the march was about 45-50 kilometers for the nomads, which is close to the performance of the Batu detachment.

The third detachment of Mongols under the command of Burundai turned out to be the “slowest” - after the capture of Vladimir, he set out for Rostov (170 kilometers in a straight line), then covered another 100 kilometers to Uglich. Part of Burundai's forces made a forced march to Yaroslavl (about 70 kilometers) from Uglich. At the beginning of March, Burundai unmistakably found the camp of Yuri Vsevolodovich in the Trans-Volga forests, whom he defeated in the battle on the Sit River on March 4. The transition from Uglich to the City and back is about 130 kilometers. In total, Burundai's troops covered about 470 kilometers in 25 days - this gives us only 19 kilometers of the average daily march.

In general, the conditional average Mongolian horse clocked up “on the speedometer” from December 1, 1237 to March 4, 1238 (94 days) from 1200 (the minimum estimate, suitable only for a small part of the Mongol army) to 1800 kilometers. The conditional daily journey ranges from 12-13 to 20 kilometers. In reality, if we throw out standing in the floodplain of the Oka River (about 15 days), 5 days of the assault on Moscow and 7 days of rest after its capture, the five-day siege of Vladimir, as well as another 6-7 days for the sieges of Russian cities in the second half of February, it turns out that Mongolian horses covered an average of 25-30 kilometers for each of their 55 days of movement. These are excellent results for horses, taking into account the fact that all this happened in the cold, in the middle of forests and snowdrifts, with a clear lack of feed (it is unlikely that the Mongols could requisition a lot of feed from the peasants for their horses, especially since the steppe horses did not eat practically grain) and hard work.

After the capture of Torzhok, the main part of the Mongol army concentrated on the upper Volga in the Tver region. They then moved in the first half of March 1238 on a broad front south into the steppe. The left wing, under the command of Kadan and Buri, passed through the forests of the Klyazma and Volga watershed, then went to the upper reaches of the Moscow River and descended along it to the Oka. In a straight line it is about 400 kilometers, taking into account the average pace of movement of fast-moving nomads - this is about 15-20 days of travel for them. So, apparently, already in the first half of April this part of the Mongol army entered the steppe. We have no information about how the melting of snow and ice on the rivers affected the movement of this detachment (the Ipatiev Chronicle only reports that the steppe inhabitants moved very quickly). There is also no information about what this detachment did the next month after entering the steppe; it is only known that in May Kadan and Buri came to the rescue of Batu, who by that time was stuck near Kozelsk.

Small Mongol detachments, probably, as V.V. believes. Kargalov and R.P. Khrapachevsky, remained on the middle Volga, plundering and burning Russian settlements. How they came out into the steppe in the spring of 1238 is not known.

Most of the Mongol army under the command of Batu and Burundai, instead of taking the shortest route to the steppe, which the detachments of Kadan and Buri took, chose a very intricate route:

More is known about Batu’s route - from Torzhok he moved along the Volga and Vazuza (a tributary of the Volga) to the interfluve of the Dnieper, and from there through the Smolensk lands to the Chernigov city of Vshchizh, lying on the banks of the Desna, writes Khrapachevsky. Having made a detour along the upper reaches of the Volga to the west and northwest, the Mongols turned south and, crossing watersheds, went to the steppes. Probably some detachments were marching in the center, through Volok-Lamsky (through the forests). Approximately, the left edge of Batu covered about 700-800 kilometers during this time, other detachments a little less. By April 1, the Mongols reached Serensk, and Kozelsk (the chronicle Kozeleska, to be precise) - April 3-4 (according to other information - already March 25). On average, this gives us about 35-40 more kilometers of daily march (and the Mongols no longer walk on the ice of rivers, but through dense forests on watersheds).

Near Kozelsk, where ice drift on Zhizdra and snow melting in its floodplain could already begin, Batu was stuck for almost 2 months (more precisely, for 7 weeks - 49 days - until May 23-25, maybe later, if we count from April 3, and according to Rashid ad-Din - generally for 8 weeks). Why the Mongols necessarily needed to besiege an insignificant, even by medieval Russian standards, town that had no strategic significance is not entirely clear. For example, the neighboring towns of Krom, Spat, Mtsensk, Domagoshch, Devyagorsk, Dedoslavl, Kursk were not even touched by the nomads.

Historians are still arguing on this topic; no sane argument has been given. The funniest version was proposed by the folk historian of the “Eurasian persuasion” L.N. Gumilyov, who suggested that the Mongols were taking revenge on their grandson Prince of Chernigov Mstislav, who ruled in Kozelsk, for the murder of ambassadors on the Kalka River in 1223. It’s funny that the Smolensk prince Mstislav the Old was also involved in the murder of the ambassadors. But the Mongols did not touch Smolensk...

Logically, Batu had to quickly leave for the steppes, since the spring thaw and lack of food threatened him with the complete loss of, at a minimum, “transport” - that is, horses.

None of the historians was puzzled by the question of what the horses and the Mongols themselves ate while besieging Kozelsk for almost two months (using standard stone-throwing machines). Finally, it is simply difficult to believe that a town with a population of several hundred, even a couple of thousand people, a huge army of the Mongols, numbering tens of thousands of soldiers, and supposedly having unique siege technologies and equipment, could not take 7 weeks...

As a result, near Kozelsk, the Mongols allegedly lost up to 4,000 people, and only the arrival of the troops of Buri and Kadan in May 1238 from the steppes saved the situation - the town was finally taken and destroyed. For the sake of humor it is worth saying that ex-president Russian Federation Dmitry Medvedev, in honor of the services of the population of Kozelsk to Russia, awarded the settlement the title of "City military glory"The humor was that archaeologists, after almost 15 years of searching, were unable to find unambiguous evidence of the existence of Kozelsk destroyed by Batu. You can talk about what passions were boiling about this in the scientific and bureaucratic community of Kozelsk.

If we summarize the estimated data in a first and very rough approximation, it turns out that from December 1, 1237 to April 3, 1238 (the beginning of the siege of Kozelsk), a conventional Mongol horse traveled on average from 1,700 to 2,800 kilometers. In terms of 120 days, this gives an average daily journey ranging from 15 to 23-odd kilometers. Since periods of time are known when the Mongols did not move (sieges, etc., and this is about 45 days in total), the scope of their average daily actual march spreads from 23 to 38 kilometers per day.

Simply put, this means more than intense stress on the horses. The question of how many of them survived after such transitions in rather harsh climatic conditions and an obvious lack of food is not even discussed by Russian historians. As well as the question of the Mongolian losses themselves.

For example, R.P. Khrapachevsky generally believes that during the entire Western campaign of the Mongols in 1235-1242, their losses amounted to only about 15% of their original number, while historian V.B. Koshcheev counted up to 50 thousand sanitary losses during the campaign in North-Eastern Rus' alone. However, all these losses - both in people and horses, the brilliant Mongols quickly made up for at the expense of... the conquered peoples themselves. Therefore, already in the summer of 1238, the armies of Batu continued the war in the steppes against the Kipchaks, and in Europe in 1241, I don’t understand what kind of army invaded - so, Thomas of Splitsky reports that it had great amount... Russians, Kipchaks, Bulgars, Mordovians, etc. peoples It is not really clear how many of them there were “Mongols” themselves.

XIV. MONGOL-TATARS. – GOLDEN HORDE

(continuation)

The rise of the Mongol-Tatar Empire. – Batu’s campaign against Eastern Europe. – Military structure of the Tatars. - Invasion of Ryazan land. – Ruin Suzdal land and the capital city. – Defeat and death of Yuri II. – Reverse movement to the steppe and the ruin of Southern Rus'. - Fall of Kyiv. – Trip to Poland and Hungary.

For the invasion of the Tatars in Northern Rus', the Lavrentievsky (Suzdal) and Novgorod chronicles are used, and for the invasion of Southern Russia - the Ipatievsky (Volynsky). The latter is told in a very incomplete manner; so we have the most scant news about the actions of the Tatars in the Kyiv, Volyn and Galician lands. We find some details in later vaults, Voskresensky, Tverskoy and Nikonovsky. In addition, there was a special legend about Batu’s invasion of Ryazan land; but published in Vremennik Ob. I. and Dr. No. 15. (About him, in general about the devastation of the Ryazan land, see my “History of the Ryazan Principality,” Chapter IV.) Rashid Eddin’s news about Batu’s campaigns was translated by Berezin and supplemented with notes (Journal of M.N. Pr. 1855. No. 5 ). G. Berezin also developed the idea of the Tatar method of operating by raid.

For the Tatar invasion of Poland and Hungary, see the Polish-Latin chronicles of Bogufal and Dlugosz. Ropel Geschichte Polens. I. Th. Palatsky D jiny narodu c "eskeho I. His Einfal der Mongolen. Prag. 1842. Mailata Ceschichte der Magyaren. I. Hammer-Purgstal Geschichte der Goldenen Horde. Wolf in his Geschichte der Mongolen oder Tataren, by the way (chap. VI) , exposes critical review stories of the named historians about the Mongol invasion; in particular, he tries to refute Palacki’s presentation in relation to the modus operandi of the Czech king Wenzel, as well as in relation to the well-known legend about the victory of Jaroslav Sternberk over the Tatars at Olomouc.

Mongol-Tatar Empire after Genghis Khan

Meanwhile, a menacing cloud moved in from the east, from Asia. Genghis Khan assigned the Kipchak and the entire side to the north and west of the Aral-Caspian to his eldest son Jochi, who was to complete the conquest of this side begun by Jebe and Subudai. But the attention of the Mongols was still diverted by the stubborn struggle in eastern Asia with two strong kingdoms: the Niuchi empire and the neighboring Tangut power. These wars delayed the defeat of Eastern Europe for more than ten years. Moreover, Jochi died; and he was soon followed by Temujin [Genghis Khan] himself (1227), having managed to personally destroy the Tangut kingdom before his death. Three sons survived after him: Jagatai, Ogodai and Tului. He appointed Ogodai as his successor, or supreme khan, as the most intelligent among the brothers; Jagatai was given Bukharia and eastern Turkestan, Tula - Iran and Persia; and Kipchak was to come into the possession of the sons of Jochi. Temujin bequeathed to his descendants to continue the conquests and even drew for them overall plan actions. The Great Kurultai, assembled in his homeland, that is, on the banks of Kerulen, confirmed his orders. Ogodai, who was in charge of the Chinese war, tirelessly continued this war until he completely destroyed the Niuchi empire and established his rule there (1234). Only then did he pay attention to other countries and, by the way, began to cook great march to Eastern Europe.

During this time, the Tatar temniks, who commanded the Caspian countries, did not remain inactive; and tried to keep the nomads subdued by Jebe Subudai in subjection. In 1228, according to the Russian chronicle, “from below” (from the Volga) the Saksins (a tribe unknown to us) and Polovtsi, pressed by the Tatars, ran into the borders of the Bulgarians; The Bulgarian guard detachments they had defeated also came running from the country of Priyaitskaya. Around the same time, in all likelihood, the Bashkirs, fellow tribesmen of the Ugrians, were conquered. Three years later, the Tatars undertook a reconnaissance campaign deep into Kama Bulgaria and spent the winter there somewhere short of the Great City. The Polovtsians, for their part, apparently took advantage of the circumstances to defend their independence with weapons. At least their main khan Kotyan later, when he sought refuge in Ugria, told the Ugric king that he had defeated the Tatars twice.

Beginning of Batu's invasion

Having put an end to the Niuchi Empire, Ogodai moved the main forces of the Mongol-Tatars to conquer Southern China, Northern India and the rest of Iran; and for the conquest of Eastern Europe he allocated 300,000, the leadership of which he entrusted to his young nephew Batu, the son of Dzhuchiev, who had already distinguished himself in the Asian wars. His uncle appointed the famous Subudai-Bagadur as his leader, who, after the Kalka victory, together with Ogodai, completed the conquest Northern China. The Great Khan gave Batu and other proven commanders, including Burundai. Many young Genghisids also took part in this campaign, by the way, the son of Ogodai Gayuk and the son of Tului Mengu, the future successors of the Great Khan. From the upper reaches of the Irtysh, the horde moved westward, along the nomadic camps of various Turkish hordes, gradually annexing significant parts of them; so that at least half a million warriors crossed the Yaik River. One of the Muslim historians, speaking about this campaign, adds: “The earth groaned from the multitude of warriors; the troops went mad from the sheer numbers wild animals and night birds." This was no longer the selected cavalry that launched the first raid and fought on Kalka; now a huge horde with its families, wagons and herds was moving slowly. It constantly migrated, stopping where it found sufficient pastures for its horses and other livestock Having entered the Volga steppes, Batu himself continued to move to the lands of the Mordovians and Polovtsians, and to the north he separated part of the troops with Subudai-Bagadur for the conquest of Kama Bulgaria, which the latter accomplished in the fall of 1236. This conquest, according to Tatar custom, was accompanied by a terrible devastation of the land and beating the inhabitants; by the way, the Great City was taken and set on fire.

Khan Batu. Chinese drawing from the 14th century

By all indications, Batu’s movement was carried out according to a premeditated method of action, based on preliminary intelligence about those lands and peoples that it was decided to conquer. At least this can be said about the winter campaign in Northern Rus'. Obviously, the Tatar military leaders already had accurate information about what time of year is most favorable for military operations in this wooded area, replete with rivers and swamps; among them, the movement of the Tatar cavalry would be very difficult at any other time, with the exception of winter, when all the waters are covered with ice, strong enough to endure horse hordes.

Military organization of the Mongol-Tatars

Only the invention of European firearms and the establishment of large standing armies brought about a revolution in the attitude of sedentary and agricultural peoples to nomadic and pastoral peoples. Before this invention, the advantage in the fight was often on the side of the latter; which is very natural. Nomadic hordes are almost always on the move; their parts always more or less stick together and act as a dense mass. Nomads have no differences in occupations and habits; they are all warriors. If the will of an energetic khan or circumstances united a large number of hordes into one mass and directed them towards sedentary neighbors, then it was difficult for the latter to successfully resist the destructive impulse, especially where the nature was flat. The agricultural people, scattered throughout their country, accustomed to peaceful occupations, could not soon gather into a large militia; and even this militia, if it managed to set out on time, was far inferior to its opponents in speed of movement, in the habit of wielding weapons, in the ability to act in harmony and onslaught, in military experience and resourcefulness, as well as in a warlike spirit.

All such qualities in high degree owned by the Mongol-Tatars when they came to Europe. Temujin [Genghis Khan] gave them the main weapon of conquest: unity of power and will. While nomadic peoples are divided into special hordes, or clans, the power of their khans, of course, has the patriarchal character of the ancestor and is far from unlimited. But when, by force of arms, one person subjugates entire tribes and peoples, then, naturally, he rises to a height unattainable for a mere mortal. Old customs still live among these people and seem to limit the power of the Supreme Khan; The guardians of such customs among the Mongols are kurultai and noble influential families; but in the hands of the clever, energetic khan many resources have already been concentrated to become a limitless despot. Having imparted unity to the nomadic hordes, Temujin further strengthened their power by introducing a uniform and well-adapted military organization. The troops deployed by these hordes were organized on the basis of strictly decimal division. The tens united into hundreds, the latter into thousands, with tens, hundreds and thousands at the head. Ten thousand made up the largest department called “fogs” and were under the command of the temnik. Place of the former more or less open relationship Strict military discipline came to the leaders. Disobedience or premature removal from the battlefield was punishable by death. In case of indignation, not only the participants were executed, but their entire family was condemned to extermination. The so-called Yasa (a kind of code of laws) published by Temuchin, although it was based on old Mongol customs, significantly increased their severity in relation to various actions and was truly draconian or bloody in nature.

The continuous and long series of wars started by Temujin developed among the Mongols strategic and tactical techniques that were remarkable for that time, i.e. general art of war. Where terrain and circumstances did not interfere, the Mongols operated in enemy soil by round-up, in which they are especially accustomed; since in this way the Khan usually hunted wild animals. The hordes were divided into parts, marched in encirclement and then approached the pre-designated main point, devastating the country with fire and sword, taking prisoners and all kinds of booty. Thanks to their steppe, short, but strong horses, the Mongols were able to make unusually fast and long marches without rest, without stopping. Their horses were hardened and accustomed to endure hunger and thirst just like their riders. Moreover, the latter usually had several spare horses with them on campaigns, which they transferred to as needed. Their enemies were often amazed by the appearance of barbarians at a time when they considered them to be still far away from them. Thanks to such cavalry, the Mongols' reconnaissance unit was at a remarkable stage of development. Any movement of the main forces was preceded by small detachments, scattered in front and on the sides, as if in a fan; Observation detachments also followed behind; so that the main forces were secured against any chance or surprise.

Regarding weapons, although the Mongols had spears and curved sabers, they were predominantly riflemen (some sources, for example, Armenian chroniclers, call them “the people of riflemen”); They used bows with such strength and skill that their long arrows, tipped with an iron tip, pierced hard shells. Usually the Mongols first tried to weaken and frustrate the enemy with a cloud of arrows, and then rushed at him hand-to-hand. If at the same time they met a courageous resistance, they turned to feigned flight; As soon as the enemy began to pursue them and thereby upset their battle formation, they deftly turned their horses and again made a united attack from all sides, if possible. They were covered with shields woven from reeds and covered with leather, helmets and armor, also made of thick leather, some even covered with iron scales. In addition, wars with more educated and rich peoples brought them a considerable amount of iron chain mail, helmets and all kinds of weapons, which their commanders and noble people wore. The tails of horses and wild buffalos fluttered on the banners of their leaders. The commanders usually did not enter the battle themselves and did not risk their lives (which could cause confusion), but controlled the battle, being somewhere on a hill, surrounded by their neighbors, servants and wives, of course, all on horseback.

The nomadic cavalry, having a decisive advantage over sedentary peoples in the open field, however, encountered an important obstacle in the form of well-fortified cities. But the Mongols were already accustomed to dealing with this obstacle, having learned the art of taking cities in the Chinese and Khovarezm empires. They also started up battering machines. They usually surrounded a besieged city with a rampart; and where the forest was at hand, they fenced it off with a tine, thus stopping the very possibility of communication between the city and the surrounding area. Then they set up battering machines, from which they threw large stones and logs, and sometimes incendiary substances; in this way they caused fire and destruction in the city; They showered the defenders with a cloud of arrows or put up ladders and climbed onto the walls. In order to tire out the garrison, they carried out attacks continuously day and night, for which fresh detachments constantly alternated with each other. If the barbarians learned to take large Asian cities, fortified with stone and clay walls, the easier they could destroy or burn the wooden walls of Russian cities. Crossing large rivers did not make it particularly difficult for the Mongols. For this purpose they used large leather bags; they were stuffed tightly with clothes and other light things, tied tightly and tied to the tail of the horses, and thus transported. One Persian historian of the 13th century, describing the Mongols, says: “They had the courage of a lion, the patience of a dog, the foresight of a crane, the cunning of a fox, the farsightedness of a crow, the rapacity of a wolf, the battle heat of a rooster, the care of a hen for its neighbors, the sensitivity of a cat and the violence of a boar when attacked.” .

Rus' before the Mongol-Tatar invasion

What could ancient, fragmented Rus' oppose to this enormous concentrated force?

The fight against nomads of Turkish-Tatar origin was already a familiar thing for her. After the first onslaughts of both the Pechenegs and the Polovtsians, fragmented Rus' then gradually became accustomed to these enemies and gained the upper hand over them. However, she did not have time to throw them back to Asia or to subjugate them and return to their former borders; although these nomads were also fragmented and also did not submit to one power, one will. What a disparity in strength there was with the menacing Mongol-Tatar cloud now approaching!

In military courage and combat courage, the Russian squads, of course, were not inferior to the Mongol-Tatars; and they were undoubtedly superior in bodily strength. Moreover, Rus' was undoubtedly better armed; its complete armament of that time was not much different from the armament of the German and Western European armaments in general. Among her neighbors she was even famous for her fighting. Thus, regarding Daniil Romanovich’s campaign to help Konrad of Mazovia against Vladislav the Old in 1229, the Volyn chronicler notes that Konrad “loved Russian battle” and relied on Russian help more than on his Poles. But the princely squads that made up the military class of Ancient Rus' were too few in number to repel the new enemies now pressing from the east; and the common people, if necessary, were recruited into the militia directly from the plow or from their crafts, and although they were distinguished by the stamina common to the entire Russian tribe, they did not have much skill in wielding weapons or making friendly, quick movements. One can, of course, blame our old princes for not understanding all the dangers and all the disasters that were then threatening from new enemies, and not joining their forces for a united rebuff. But, on the other hand, we must not forget that where there was a long period of all kinds of disunity, rivalry and the development of regional isolation, no human will, no genius could achieve rapid unification and concentration. popular forces. Such a benefit can only be achieved through the long and constant efforts of entire generations under circumstances that awaken in the people the consciousness of their national unity and the desire for their concentration. Ancient Rus' did what was in its means and methods. Every land, almost every significant city bravely met the barbarians and desperately defended themselves, hardly having any hope of winning. It couldn't be otherwise. The great historical people are not inferior external enemy without courageous resistance, even under the most unfavorable circumstances.

Invasion of the Mongol-Tatars into the Ryazan Principality

At the beginning of the winter of 1237, the Tatars passed through the Mordovian forests and camped on the banks of some river Onuza. From here Batu sent to the Ryazan princes, according to the chronicle, a “sorceress wife” (probably a shaman) and with her two husbands, who demanded from the princes part of their estate in people and horses.

The eldest prince, Yuri Igorevich, hastened to convene his relatives, the appanage princes of Ryazan, Pron and Murom, to the Diet. In the first impulse of courage, the princes decided to defend themselves, and gave a noble answer to the ambassadors: “When we do not survive, then everything will be yours.” From Ryazan, Tatar ambassadors went to Vladimir with the same demands. Seeing that the Ryazan forces were too insignificant to fight the Mongols, Yuri Igorevich ordered this: he sent one of his nephews to the Grand Duke of Vladimir with a request to unite against common enemies; and sent another with the same request to Chernigov. Then the united Ryazan militia moved to the shores of Voronezh to meet the enemy; but avoided battle while waiting for help. Yuri tried to resort to negotiations and sent his only son Theodore at the head of a ceremonial embassy to Batu with gifts and a plea not to fight the Ryazan land. All these orders were unsuccessful. Theodore died in the Tatar camp: according to legend, he refused Batu’s demand to bring him his beautiful wife Eupraxia and was killed on his orders. Help didn't come from anywhere. The princes of Chernigovo-Seversky refused to come on the grounds that the Ryazan princes were not on Kalka when they were also asked for help; probably the Chernigov residents thought that the thunderstorm would not reach them or was still very far from them. And the slow Yuri Vsevolodovich Vladimirsky hesitated and was just as late with his help, as in the Kalka massacre. Seeing the impossibility of fighting the Tatars in an open field, the Ryazan princes hastened to retreat and took refuge with their squads behind the fortifications of the cities.

Following them, hordes of barbarians poured into the Ryazan land, and, according to their custom, engulfing it in a wide raid, began to burn, destroy, rob, beat, captivate, and commit desecration of women. There is no need to describe all the horrors of ruin. Suffice it to say that many villages and cities were completely wiped off the face of the earth; some of their famous names are no longer found in history after that. By the way, a century and a half later, travelers sailing along the upper reaches of the Don saw only ruins and deserted places on its hilly banks where once flourishing cities and villages stood. The devastation of the Ryazan land was carried out with particular ferocity and mercilessness also because it was in this regard the first Russian region: the barbarians came to it, full of wild, unbridled energy, not yet satiated with Russian blood, not tired of destruction, not reduced in number after countless battles. On December 16, the Tatars surrounded the capital city of Ryazan and surrounded it with a tyn. The squad and citizens, encouraged by the prince, repelled the attacks for five days. They stood on the walls, without changing their positions and without letting go of their weapons; Finally they began to grow exhausted, while the enemy constantly acted with fresh forces. On the sixth day the Tatars made a general attack; They threw fire on the roofs, smashed the walls with logs from their battering guns and finally broke into the city. The usual beating of residents followed. Among those killed was Yuri Igorevich. His wife and her relatives sought salvation in vain in the cathedral church of Boris and Gleb. What could not be plundered became a victim of the flames. Ryazan legends decorate the stories about these disasters with some poetic details. So, Princess Eupraxia, hearing about the death of her husband Feodor Yuryevich, threw herself from the high tower together with her little son to the ground and killed herself to death. And one of the Ryazan boyars named Evpatiy Kolovrat was on Chernigov land when the news of the Tatar pogrom came to him. He hurries to his fatherland, sees ashes hometown and is inflamed with a thirst for revenge. Having gathered 1,700 warriors, Evpatiy attacks the rear detachments of the Tatars, overthrows their hero Tavrul and finally, suppressed by the crowd, perishes with all his comrades. Batu and his soldiers are surprised at the extraordinary courage of the Ryazan knight. ( Similar stories, of course, the people consoled themselves in past disasters and defeats.) But next to examples of valor and love for the homeland among the Ryazan boyars, there were examples of betrayal and cowardice. The same legends point to a boyar who betrayed his homeland and handed himself over to his enemies. In each country, Tatar military leaders knew how to first of all find traitors; especially those were among the people captured, frightened by threats or seduced by caresses. From noble and ignorant traitors, the Tatars learned everything they needed about the state of the land, its weaknesses, the properties of the rulers, etc. These traitors also served as the best guides for the barbarians when moving into countries hitherto unknown to them.

Tatar invasion of Suzdal land

Capture of Vladimir by the Mongol-Tatars. Russian chronicle miniature

From the Ryazan land the barbarians moved to Suzdal, again in the same murderous order, sweeping this land in a raid. Their main forces went the usual Suzdal-Ryazan route to Kolomna and Moscow. Just then they were met by the Suzdal army, going to the aid of the Ryazan people, under the command of the young prince Vsevolod Yuryevich and the old governor Eremey Glebovich. Near Kolomna, the grand ducal army was completely defeated; Vsevolod escaped with the remnants of the Vladimir squad; and Eremey Glebovich fell in battle. Kolomna was taken and destroyed. Then the barbarians burned Moscow, the first Suzdal city on this side. Another son of the Grand Duke, Vladimir, and the governor Philip Nyanka were in charge here. The latter also fell in battle, and the young prince was captured. With how quickly the barbarians acted during their invasion, with the same slowness military gatherings took place in Northern Rus' at that time. With modern weapons, Yuri Vsevolodovich could put all the forces of Suzdal and Novgorod in the field in conjunction with the Murom-Ryazan forces. There would be enough time for these preparations. For more than a year, fugitives from Kama Bulgaria found refuge with him, bringing news of the devastation of their land and the movement of the terrible Tatar hordes. But instead of modern preparations, we see that the barbarians were already moving towards the capital itself, when Yuri, having lost the best part of the army, defeated piecemeal, went further north to gather the zemstvo army and call for help from his brothers. In the capital, the Grand Duke left his sons, Vsevolod and Mstislav, with the governor Peter Oslyadyukovich; and he drove off with a small squad. On the way, he annexed three nephews of the Konstantinovichs, appanage princes of Rostov, with their militia. With the army that he managed to gather, Yuri settled down beyond the Volga almost on the border of his possessions, on the banks of the City, the right tributary of the Mologa, where he began to wait for the brothers, Svyatoslav Yuryevsky and Yaroslav Pereyaslavsky. The first one actually managed to come to him; but the second one did not appear; Yes, he could hardly have appeared on time: we know that at that time he occupied the great Kiev table.

At the beginning of February, the main Tatar army surrounded the capital Vladimir. A crowd of barbarians approached the Golden Gate; the citizens greeted them with arrows. "Do not shoot!" - the Tatars shouted. Several horsemen rode up to the very gate with the prisoner and asked: “Do you recognize your prince Vladimir?” Vsevolod and Mstislav, standing on the Golden Gate, together with those around them, immediately recognized their brother, captured in Moscow, and were struck with grief at the sight of his pale, sad face. They were eager to free him, and only the old governor Pyotr Oslyadyukovich kept them from a useless desperate sortie. Having located their main camp opposite the Golden Gate, the barbarians cut down trees in the neighboring groves and surrounded the entire city with a fence; then they installed their “vices”, or battering machines, and began to destroy the fortifications. The princes, princesses and some boyars, no longer hoping for salvation, accepted monastic vows from Bishop Mitrofan and prepared for death. On February 8, the day of the martyr Theodore Stratilates, the Tatars made a decisive attack. Following a sign, or brushwood thrown into the ditch, they climbed onto the city rampart at the Golden Gate and entered the new, or outer, city. At the same time, from the side of Lybid they broke into it through the Copper and Irininsky gates, and from Klyazma - through the Volzhsky. The outer city was taken and set on fire. Princes Vsevolod and Mstislav with their retinue retired to the Pecherny city, i.e. to the Kremlin. And Bishop Mitrofan with the Grand Duchess, her daughters, daughters-in-law, grandchildren and many noblewomen locked themselves in the cathedral church of the Mother of God in the tents, or choirs. When the remnants of the squad with both princes died and the Kremlin was taken, the Tatars broke down the doors of the cathedral church, plundered it, took away expensive vessels, crosses, vestments on icons, frames on books; then they dragged the forest into the church and around the church, and lit it. The bishop and the entire princely family, hiding in the choir, died in smoke and flames. Other churches and monasteries in Vladimir were also plundered and partly burned; many residents were beaten.

Already during the siege of Vladimir, the Tatars took and burned Suzdal. Then their detachments scattered throughout the Suzdal land. Some went north, took Yaroslavl and captured the Volga region all the way to Galich Mersky; others plundered Yuryev, Dmitrov, Pereyaslavl, Rostov, Volokolamsk, Tver; During February, up to 14 cities were taken, in addition to many “settlements and graveyards.”

Battle of the City River

Meanwhile, Georgy [Yuri] Vsevolodovich still stood on the City and waited for his brother Yaroslav. Then terrible news came to him about the destruction of the capital and the death of the princely family, about the capture of other cities and the approach of Tatar hordes. He sent a detachment of three thousand for reconnaissance. But the scouts soon came running back with the news that the Tatars were already bypassing the Russian army. As soon as the Grand Duke, his brothers Ivan and Svyatoslav and his nephews mounted their horses and began to organize regiments, the Tatars, led by Burundai, attacked Rus' from different sides, on March 4, 1238. The battle was brutal; but the majority of the Russian army, recruited from farmers and artisans unaccustomed to battle, soon mixed up and fled. Here Georgy Vsevolodovich himself fell; his brothers fled, his nephews also, with the exception of the eldest, Vasilko Konstantinovich of Rostov. He was captured. The Tatar military leaders persuaded him to accept their customs and fight the Russian land together with them. The prince firmly refused to be a traitor. The Tatars killed him and threw him into some Sherensky forest, near which they temporarily camped. The northern chronicler showers Vasilko with praise on this occasion; says that he was handsome in face, intelligent, courageous and very kind-hearted (“he is light at heart”). “Whoever served him, ate his bread and drank his cup, could no longer be in the service of another prince,” the chronicler adds. Bishop Kirill of Rostov, who escaped during the invasion of the remote city of his diocese, Belozersk, returned and found the body of the Grand Duke, deprived of his head; then he took Vasilko’s body, brought it to Rostov and laid it in the cathedral church of the Mother of God. Subsequently, they also found the head of George and placed him in his coffin.

Batu's movement to Novgorod

While one part of the Tatars was moving to Sit against the Grand Duke, the other reached the Novgorod suburb of Torzhok and besieged it. The citizens, led by their mayor Ivank, courageously defended themselves; For two whole weeks the barbarians shook the walls with their guns and made constant attacks. The novotors waited in vain for help from Novgorod; at last they were exhausted; On March 5, the Tatars took the city and terribly devastated it. From here their hordes moved further and went to Veliky Novgorod along the famous Seliger route, devastating the country right and left. They had already reached the “Ignach-cross” (Kresttsy?) and were only a hundred miles from Novgorod, when they suddenly turned south. This sudden retreat, however, was very natural under the circumstances of that time. Having grown up on the high planes and mountain plains of Central Asia, characterized by a harsh climate and variable weather, the Mongol-Tatars were accustomed to cold and snow and could quite easily endure the Northern Russian winter. But also accustomed to a dry climate, they were afraid of dampness and soon fell ill from it; their horses, for all their hardiness, after the dry steppes of Asia, also had difficulty withstanding swampy countries and wet food. Spring was approaching in Northern Russia with all its predecessors, i.e. melting snow and overflowing rivers and swamps. Along with disease and horse death, a terrible thaw threatened; the hordes caught by it could find themselves in a very difficult situation; the beginning of the thaw could clearly show them what awaited them. Perhaps they also found out about the preparations of the Novgorodians for a desperate defense; the siege could be delayed for several more weeks. There is, in addition, an opinion, not without probability, that there was a raid here, and Batu recently found it inconvenient to make a new one.

Temporary retreat of the Mongol-Tatars to the Polovtsian steppe

During the return movement to the steppe, the Tatars devastated eastern part Smolensk land and Vyatichi region. Of the cities they devastated at the same time, the chronicles mention only one Kozelsk, due to its heroic defense. The appanage prince here was one of the Chernigov Olgovichs, young Vasily. His warriors, together with the citizens, decided to defend themselves until last person and did not give in to any flattering persuasion of the barbarians.

Batu, according to the chronicle, stood near this city for seven weeks and lost many killed. Finally, the Tatars smashed the wall with their cars and burst into the city; Even here the citizens continued to desperately defend themselves and cut themselves with knives until they were all beaten, and their young prince seemed to have drowned in blood. For such defense, the Tatars, as usual, nicknamed Kozelsk “the evil city.” Then Batu completed the enslavement of the Polovtsian hordes. Their main khan, Kotyan, with part of the people, retired to Hungary, and there he received land for settlement from King Bela IV, under the condition of the baptism of the Polovtsians. Those who remained in the steppes had to unconditionally submit to the Mongols and increase their hordes. From the Polovtsian steppes, Batu sent out detachments, on the one hand, to conquer the Azov and Caucasian countries, and on the other, to enslave Chernigov-Northern Rus'. By the way, the Tatars took Southern Pereyaslavl, plundered and destroyed the cathedral church of Michael there and killed Bishop Simeon. Then they went to Chernigov. Mstislav Glebovich Rylsky, Mikhail Vsevolodovich’s cousin, came to the aid of the latter and courageously defended the city. The Tatars placed throwing weapons from the walls at a distance of one and a half arrow flights and threw such stones that four people could hardly lift them. Chernigov was taken, plundered and burned. Bishop Porfiry, who was captured, was left alive and released. In the winter of the following 1239, Batu sent troops north to complete the conquest of the Mordovian land. From here they went to the Murom region and burned Murom. Then they fought again on the Volga and Klyazma; on the first they took Gorodets Radilov, and on the second - the city of Gorokhovets, which, as you know, was the possession of the Assumption Cathedral of Vladimir. This new invasion caused a terrible commotion throughout the entire Suzdal land. The residents who survived the previous pogrom abandoned their homes and ran wherever they could; mostly fled to the forests.

Mongol-Tatar invasion of Southern Rus'

Having finished with the strongest part of Rus', i.e. with the great reign of Vladimir, having rested in the steppe and fattened their horses, the Tatars now turned to Southwestern, Trans-Dnieper Rus', and from here they decided to go further to Hungary and Poland.

Already during the devastation of Pereyaslavl Russky and Chernigov, one of the Tatar detachments, led by Batu’s cousin, Mengu Khan, approached Kyiv to scout out its position and means of defense. Stopping on the left side of the Dnieper, in the town of Pesochny, Mengu, according to the legend of our chronicle, admired the beauty and grandeur of the ancient Russian capital, which picturesquely rose on the coastal hills, shining with white walls and gilded domes of its temples. The Mongol prince tried to persuade the citizens to surrender; but they did not want to hear about her and even killed the messengers. At that time, Kiev was owned by Mikhail Vsevolodovich Chernigovsky. Although Menggu left; but there was no doubt that he would return with greater forces. Mikhail did not consider it convenient for himself to wait for the Tatar thunderstorm, he cowardly left Kyiv and retired to Ugria. Soon afterwards the capital city passed into the hands of Daniil Romanovich of Volyn and Galitsky. However, this famous prince, with all his courage and the vastness of his possessions, did not appear for the personal defense of Kyiv from the barbarians, but entrusted it to the thousandth Demetrius.

In the winter of 1240, a countless Tatar force crossed the Dnieper, surrounded Kyiv and fenced it off with a fence. Batu himself was there with his brothers, relatives and cousins, as well as his best commanders Subudai-Bagadur and Burundai. The Russian chronicler clearly depicts the enormity of the Tatar hordes, saying that the inhabitants of the city could not hear each other due to the creaking of their carts, the roar of camels and the neighing of horses. The Tatars directed their main attacks on that part that had the least strong position, i.e. to the western side, from which some wilds and almost flat fields adjoined the city. The battering guns, especially concentrated against the Lyadsky Gate, beat the wall day and night until they made a breach. The most persistent slaughter took place, “spear breaking and shields clumping together”; clouds of arrows darkened the light. The enemies finally broke into the city. The people of Kiev, with a heroic, albeit hopeless defense, supported the ancient glory of the first throne of the Russian city. They gathered around the Tithe Church of the Virgin Mary and then at night hastily fenced themselves off with fortifications. The next day this last stronghold also fell. Many citizens with families and property sought salvation in the choirs of the temple; the choirs could not withstand the weight and collapsed. This capture of Kyiv took place on December 6, on St. Nicholas’ day. The desperate defense embittered the barbarians; sword and fire spared nothing; the inhabitants were mostly beaten, and the majestic city was reduced to one huge heap of ruins. Tysyatsky Dimitri, captured wounded, Batu, however, left alive “for the sake of his courage.”

Having devastated the Kyiv land, the Tatars moved to Volyn and Galicia, took and destroyed many cities, including the capital Vladimir and Galich. Only some places, well fortified by nature and people, they could not take in battle, for example, Kolodyazhen and Kremenets; but they still took possession of the first, persuading the inhabitants to surrender with flattering promises; and then they were treacherously beaten. During this invasion, part of the population of Southern Rus' fled to distant countries; many took refuge in caves, forests and wilds.

Among the owners of South-Western Rus' there were those who, at the very appearance of the Tatars, submitted to them in order to save their inheritance from ruin. This is what the Bolokhovskys did. It is curious that Batu spared their land on the condition that its inhabitants sow wheat and millet for the Tatar army. It is also remarkable that Southern Rus', compared to Northern Russia, offered much weaker resistance to the barbarians. In the north, the senior princes, Ryazan and Vladimir, having gathered the forces of their land, bravely entered into an unequal struggle with the Tatars and died with weapons in their hands. And in the south, where the princes have long been famous for their military prowess, we see a different course of action. The senior princes, Mikhail Vsevolodovich, Daniil and Vasilko Romanovich, with the approach of the Tatars, left their lands to seek refuge either in Ugria or in Poland. It’s as if the princes of Southern Rus' had enough determination for a general resistance only during the first invasion of the Tatars, and the Kalka massacre brought such fear into them that its participants, then young princes, and now older ones, are afraid of another meeting with wild barbarians; they leave their cities to defend themselves alone and perish in an overwhelming struggle. It is also remarkable that these senior southern Russian princes continue their feuds and scores for the volosts at the very time when the barbarians are already advancing on their ancestral lands.

Campaign of the Tatars to Poland

After Southwestern Rus', it was the turn of the neighboring Western countries, Poland and Ugria [Hungary]. Already during his stay in Volyn and Galicia, Batu, as usual, sent detachments to Poland and the Carpathians, wanting to scout out the routes and position of those countries. According to the legend of our chronicle, the aforementioned governor Dimitri, in order to save South-Western Rus' from complete devastation, tried to speed up the further campaign of the Tatars and told Batu: “Don’t hesitate long in this land; it’s time for you to go to the Ugrians; and if you hesitate, then there They will have time to gather strength and will not let you into their lands." Even without this, the Tatar leaders had the custom of not only obtaining all the necessary information before a campaign, but also with quick, cunningly planned movements to prevent any concentration of large forces.

The same Dimitri and other southern Russian boyars could tell Batu a lot about the political state of their western neighbors, whom they often visited together with their princes, who were often related to both the Polish and Ugric sovereigns. And this state was likened to fragmented Rus' and was very favorable for the successful invasion of the barbarians. In Italy and Germany at that time, the struggle between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines was in full swing. The famous grandson of Barbarossa, Frederick II, sat on the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. The aforementioned struggle completely distracted his attention, and in the very era of the Tatar invasion, he was diligently engaged in military operations in Italy against the supporters of Pope Gregory IX. Poland, being divided into appanage principalities, just like Rus', could not act unanimously and present serious resistance to the advancing horde. IN this era we see here the two eldest and most powerful princes, namely, Konrad of Mazovia and Henry the Pious, ruler of Lower Silesia. They were on hostile terms with each other; moreover, Conrad, already known for his short-sighted policy (especially calling on the Germans to defend their land from the Prussians), was least capable of a friendly, energetic course of action. Henry the Pious was related to the Czech king Wenceslaus I and the Ugric Bela IV. In view of the threatening danger, he invited the Czech king to meet the enemies with joint forces; but did not receive timely help from him. In the same way, Daniil Romanovich had long been convincing the Ugric king to unite with Russia to repel the barbarians, and also to no avail. The Kingdom of Hungary at that time was one of the strongest and richest states in all of Europe; his possessions extended from the Carpathians to the Adriatic Sea. The conquest of such a kingdom should have especially attracted the Tatar leaders. They say that Batu, while still in Russia, sent envoys to the Ugric king demanding tribute and submission and reproaches for accepting the Kotyanov Polovtsians, whom the Tatars considered their runaway slaves. But the arrogant Magyars either did not believe in the invasion of their land, or considered themselves strong enough to repel this invasion. With his own sluggish, inactive character, Bela IV was distracted by various disorders of his state, especially feuds with rebellious magnates. These latter, by the way, were dissatisfied with the installation of the Polovtsians, who carried out robberies and violence, and did not even think of leaving their steppe habits.