Artists still lifes with flowers. The best still lifes

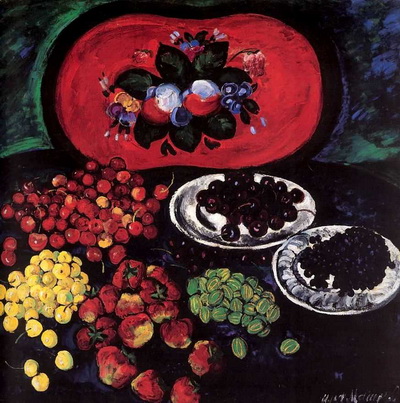

I. Mashkov "Still Life" (1930)

The word "still life" French translated as "dead nature" (fr. nature morte).

About still life

Everything that no longer lives, breathes, that is torn off, cut off, but continues to please a person with its existence - all this is the subject of a still life.

As an independent genre of painting, still life begins to exist in the 17th century. in the work of Dutch and Flemish artists. And earlier it was only an ornament and performed a utilitarian function.

Early still lifes often contained hidden allegory (allegory), which was expressed through everyday objects endowed with symbolic meaning. Sometimes a skull was depicted in still lifes, which was supposed to remind of the transience of life and the inevitability of death.

The allegorical still life was called Vanitas (lat. vanitas lit.: "vanity, vanity"). Its compositional center is traditionally a human skull.

Bartholomeus Brain the Elder (I half of the 16th century). Vanitas

“Vanity of vanities,” said the Ecclesiastes, “vanity of vanities, all is vanity!”

Willem Claesz Heda. Vanitas

The skull symbolizes frailty human life. A smoking pipe is a symbol of fleeting and elusive earthly pleasures. Glass symbolizes the fragility of life. The keys are the power of the housewife managing the inventory. The knife reminds of the vulnerability of a person and his mortality. A sheet of paper usually with a moralizing (often pessimistic) saying. For example:

Hodie mihi cras tibi - today for me, tomorrow for you;

memento mori - memento Mori;

Aeterne pungit cito volat et occidit - the glory of heroic deeds will vanish in the same way as a dream;

Omnia morte cadunt mors ultima linia rerum - everything is destroyed by death, death - last border all things;

Nil omne - everything is nothing.

But more often, nevertheless, in still lifes, one feels the artist’s admiration for objects: kitchen utensils, flowers, fruits, household items - such paintings were purchased by customers to decorate the interiors of their homes.

From the middle of the XVII century. still life in Dutch painting received wide use already as an independent genre. And one of the very first was the floral still life, especially in the works of Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder and Balthasar van der Ast, and then continued its development in the luxurious still lifes of Jan Davidsz de Heem in the second half of the 17th century. Floral still life is also popular among artists of our time.

The subject of still lifes is extensive: these are the already mentioned flower still lifes, the image of breakfasts, served tables, scientists' still lifes, which depicted books and other objects of human activity, musical instruments and etc.

Consider some of the most famous still lifes.

Willem Claesz Heda (1594-1682) "Still life with ham and silverware" (1649)

Willem Claesz Heda "Still life with ham and silverware" (1649)

In this picture, the artist's virtuoso skill in the transfer of ordinary, everyday household items is noticeable. Kheda depicts them in such a way that it is obvious that he himself admires them: a feeling of tangibility of each of the objects is created.

On a small table covered with a rich heavy tablecloth, we see a lemon and admire its amber softness, smell fresh ham and hear the ringing of sparkling silver. Breakfast is over, so the items on the table are in natural disorder.

Silverware means earthly wealth, ham - sensual joys, lemon - external beauty within which lies bitterness. The picture concludes a reflection on the need to take care not only of the body, but also of the soul.

The still life is designed in a single brown-gray tone, characteristic of all Dutch painting of that time. The canvas is not only beautiful, it also tells about the hidden "quiet life" of objects, seen by the artist's attentive gaze.

The still life is in the State Museum fine arts them. A. S. Pushkin in Moscow.

Paul Cezanne (1830-1906) Peaches and Pears (1895)

Paul Cezanne "Peaches and Pears" (1895)

Paul Cezanne was the greatest French painter late XIX in. Having experienced the influence of impressionism, Cezanne opposed them with his own method. He spoke out against their desire to follow in art only their visual impression - he was in favor of an objective transmission of reality, based on patterns in nature. He wanted to see not changeable, but constant qualities. Cezanne said: "I want to restore eternity to nature." The artist conducted his creative searches through the synthesis of form and color, form and space. Especially this search can be traced in his still lifes.

Each of the objects in this still life is depicted from a different point of view. We see the table from above, the tablecloth and fruit from the side, the table from below, and the jug at the same time. different points vision. Cezanne strives to show as fully as possible the shape and volume characteristic of peaches and pears. His technique is based on an optical law: warm colors (red, pink, yellow, golden) seem to us to protrude, and cold colors (blue, cyan, green) recede into the depths of the canvas.

The form of objects in Cezanne's still lifes does not depend on random lighting, but becomes constant, inherent in each object. Therefore, Cezanne's still lifes seem monumental.

The painting is in the State Museum of Fine Arts. A. S. Pushkin in Moscow.

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) Blue Tablecloth (1909)

Henri Matisse "The Blue Tablecloth" (1909)

The famous French artist Henri Matisse in foreign art of the XX century. occupies one of the leading positions. But this place is special.

At the very beginning of the 20th century. Matisse became the head of the first new group in European painting, which was called Fauvism(from French "wild"). A feature of this trend was the freedom to use any color arbitrarily chosen by the artist, the desire for decorative colorfulness. This was a challenge to the established norms of official art.

But after a while this group broke up, and Matisse no longer belonged to any direction, but chose his own path. With his clear, cheerful art, Matisse sought to give peace to the tormented souls of people in the emotional atmosphere of the 20th century.

In the Blue Tablecloth still life, Matisse uses his favorite compositional technique: the fabric descending from above. Matter in the foreground, as it were, closes the space of the canvas, making it shallow. The viewer admires the whimsical play of the blue ornament on the turquoise background of the tablecloth, the lines of the still life objects. The artist generalized the forms of a golden coffee pot, a green decanter and ruddy apples in a vase, they lost their volume, and small objects obeyed the rhythm of the fabric, they complement the colorful accent of the picture.

Still life in Russian painting

Still life as an independent genre of painting appeared in Russia at the beginning of the 18th century, but initially it was considered as a “lower” genre. Most often it was used as educational setting and was allowed only in a limited sense as painting flowers and fruits.

But at the beginning of the twentieth century. still life in Russian painting flourished and for the first time became an equal genre. Artists were looking for new opportunities in the field of color, form, still life composition. Among the Russian naturmorists can be called I.F. Khrutsky, I.E. Grabar, P.P. Konchalovsky, I. Levitan, A. Osmerkin, K. Petrov-Vodkin, M. Saryan, V. Nesterenko and others.

by the most famous still life P. Konchalovsky is his "Lilac".

P. Konchalovsky "Lilac" (1939)

P. Konchalovsky "Lilac" (1939)

P. Konchalovsky in painting was a follower of Cezanne, he sought to express the festivity of color inherent in Russian folk art, with the help of Paul Cezanne's color constructibility. The artist gained fame precisely thanks to his still lifes, often executed in a style close to cubism and fauvism.

His still life "Lilac" is full of this festive color, pleasing to the eye and imagination. It seems that the spring scent of lilac comes from the canvas.

The clusters of lilacs are depicted in a generalized way, but the inner memory tells us the outlines of each flower in the cluster, and therefore Konchalovsky's painting seems realistic.

I. Mashkov, a contemporary of Konchalovsky, was no less generous in depicting the materiality of the world, the colorfulness of the palette.

I. Mashkov "Berries against the background of a red tray" (1910)

There is also a riot of colors in this still life, the ability to enjoy every moment that life gives, because every moment is beautiful.

All subjects of the still life are familiar to us, but it is felt that the artist admires the generosity of nature, the richness of the surrounding world and invites us to share this joy with him.

V. Nesterenko "Father of the Fatherland" (1997)

This is a still life by contemporary artist V. Nesterenko. The theme of the painting is expressed in its title, and the content is revealed in the image of still life objects - symbols of the imperial power of Peter I. The portrait of the emperor is located against the backdrop of a battle scene, of which there were many in his life. It makes no sense to retell all those deeds for which Peter I is called the father of the Fatherland. You can hear different opinions about the activities of the first Russian emperor, but in this case the artist expresses his opinion, and this opinion is expressed by him very convincingly.

Still life is in the Kremlin, in the reception room of the President of the Russian Federation.

Attitudes towards still life changed in different eras, sometimes it was almost forgotten, and sometimes it was the most popular genre of painting. As an independent genre of painting, it appeared in the work of Dutch artists in the 17th century. In Russia, for a long time, still life was treated as a lower genre, and only at the beginning of the 20th century did it become a full-fledged genre. Over a four-century history, artists have created a very a large number of still lifes, but even among this number one can single out the most famous and significant works for the genre.

"Still life with ham and silverware" (1649) Willem Claesz Heda (1594-1682).

The Dutch artist was a recognized master of still life, but it is this painting that stands out in his work. Here, Kheda's virtuoso mastery in the transfer of everyday household items is noticeable - a feeling of the reality of each of them is created. On a table covered with a rich tablecloth, there is an amber lemon, a piece of fresh ham and silverware. Tomorrow is just finished, so there's a slight mess on the table, which makes the picture even more real. Like most Dutch still lifes of this period, here each object carries some kind of semantic load. So, silverware speaks of earthly wealth, ham denotes sensual joys, and lemon - external beauty that hides inner bitterness. Through these symbols, the artist reminds us that we should think more about the soul, and not just about the body. The picture is made in a single brown-gray scale, characteristic of all Dutch painting of this era. In addition to the obvious decorativeness, this still life also tells about the inconspicuous "quiet life" of objects, which was noticed by the artist's attentive gaze.

"Peaches and Pears" (1895) Paul Cezanne (1830-1906).

The genre of still life has always been very conservative. Therefore, almost until the beginning of the 20th century, it looked the same as in the 17th century. Until Paul Cezanne took over. He believed that painting should objectively convey reality, and paintings should be based on the laws of nature. Cezanne sought to convey not the changeable, but the constant qualities of the subject, through the synthesis of form and color, the unification of form and space. And the genre of still life has become an excellent object for these experiments. Each of the objects in the Peaches and Pears still life is depicted from different angles. So we see the table from above, the fruit and the tablecloth - from the side, the small table - from below, and the jug in general at the same time as different sides. Cezanne tries to convey the shape and volume of peaches and pears as accurately as possible. To do this, he uses optical laws, so warm shades (red, pink, yellow, golden) are perceived by us as speakers, and cold ones (blue, blue, green) are receding into the depths. Therefore, the form of objects in his still lifes does not depend on lighting, but becomes constant. That is why Cezanne look monumental.

The Blue Tablecloth (1909) Henri Matisse (1869-1954).

Well, let's see some more pictures, shall we?

Unexpected still lifes - this is because we usually expect completely different subjects from their authors. Traditionally, these artists worked in completely different genres, preferring landscape, portrait or genre painting. Only occasionally did something get into their heads and they exclaimed: "And I'll draw this vase with tuberose!" True, this happened very rarely. So rare that I had to rummage through the sources for half a day to find their still lifes.

LET'S START WITH OUR:

Marc Chagall "White flowers on a red background". 1970. Mark has only a couple of still lifes painted in already adulthood, and then he, accustomed to the depiction of human-animal phantasmagories, could not resist in any of them - even a piece of a human physiognomy, at least somewhere with a piece of bread, let him insert it.

I, for example, love still lifes very much, but most artists do not. Somehow this is not solid for a venerable creator, all students learn the basics of drawing from staged still lifes.

Still life was especially unpopular in the second half of the 19th century, to the greatest extent - among the Impressionists, our Wanderers also disliked it. Some of them I did not find a single still life. There are no such works and, for example, Nesterov, Kuindzhi, Aivazovsky, Perov, Grigory Myasoedov (whoever finds, tell me, I will add).

Viktor Vasnetsov "Bouquet". A fabulous or epic story - please, the Kyiv Vladimir Cathedral is easy to paint, but the artist does not have a lot of still lifes. However, they are!

Of course, there are exceptions among the Impressionists - Cezanne was very fond of still lifes, although he did not consider himself an Impressionist. The post-impressionists Van Gogh and Matisse "came off" on still lifes (I will not cover the listed ones here - we are hunting for rare works of still life "dislikers"). But, basically, representatives of these trends did not like this flower-fruit business - bourgeois and patriarchal, without a favorite plein air - boredom! Even Berthe Morisot is the only girl among the Impressionists, and she did not like this slightly "girly" genre.

Ilya Repin "Apples and leaves", 1879

. Still life - not typical for Repin. Even here, the composition does not look like a classical production - all this can be lying somewhere on the ground under a tree, no glasses and draperies.

Still life did not always go through bad times. It began to appear in the 16th century, while as part of genre paintings, and in the 17th century, thanks to the Dutch, it grew into an independent genre of painting. It was very popular in the 18th and in the first half of the 19th century, and then, thanks to innovative movements in art, its popularity began to fall. The revival of fashion for still life began around the 20s of the 20th century. Many artist representatives contemporary art again they took up vases and peaches, but these were already new forms. Of course, the genre never completely died out, and there was (and still is) a whole galaxy of still life painters. We will talk about this later, but for now I will be silent, I will only comment on something, and you just look at the rare still lifes of the authors who wrote them only occasionally:

Valentin Serov "Lilac in a vase", 1887.

In his famous works, you can see only a piece of still life - peaches in front of a girl. The most penetrating portrait painter, apparently, was bored with painting flowers and the corpses of birds.

Isaac Levitan. "Forest violets and forget-me-nots", 1889.The genius of the Russian landscape sometimes painted wonderful still lifes. But very rarely! There is also a jug of dandelions - lovely!

Vasily Surikov "Bouquet".

The author of The Morning of the Streltsy Execution loved scope and drama. But this is also preserved - a little naive and charming roses.

Boris Kustodiev. "Still life with pheasants", 1915

. Often in his works there are huge still lifes - he painted merchants and ruddy peasants at tables literally bursting with food. And in general, his cheerful bright canvases look like a still life, even if it is a portrait, but there are few individual images of not a merchant's wife, but her breakfast.

Victor Borisov-Musatov "Lilac", 1902.

I really like his original dense, no one else's similar. You can always recognize him, and in this still life - too.

Mikhail Vrubel "Flowers in a blue vase", 1886

What a talent! How insultingly little time! The flowers are also gorgeous, as are the demons.

Vasily Tropinin "Snipe and Bullfinch", 1820s.

The serf artist seems to have treated the genre of still life without much reverence, and therefore almost never painted it. What you see is not even a full-fledged canvas, but a study.

Kazimir Malevich. "Still life". And you thought his apples were square?

Ivan Kramskoy "Bouquet of flowers. Phloxes", 1884

I wanted to go straight to the dacha - I also had phloxes there in the summer.

Wassily Kandinsky "Fish on a Blue Plate" Not everything is completely in squiggles yet, eyes and even a mouth are traced in the picture, and they are even nearby!

Nathan Altman "Mimosa", 1927

I like. There's something about it.

Ivan Shishkin, 1855.

And where are the bears and the forest ?!

I also wanted to insert Petrov-Vodkin, but he had quite a lot of still lifes, as it seemed. And Mashkov, Lentulov, Konchalovsky, so they are not suitable for this post.

FOREIGN:

Egon Schiele "Still Life", 1918

And you thought he only knew how to draw naked minors?

Alfred Sisley. "Still life with a heron". Dead birds - drama in everyday life.

More Sisley. Well, I love him!

Gustave Courbet. Apples and pomegranates on a platter. 1871

Edgar Degas "Woman seated at a vase of flowers", 1865

Despite the name, the woman occupies 30 percent of the area of the canvas, so she considered it to be a still life. In general, Degas liked to draw people much more than flowers. Especially ballerinas.

Eugene Delacroix. "Bouquet".

Well, thank God, no one eats anyone and no one shoots!

Theodore Géricault "Still life with three skulls"

In general, Gericault somehow suspiciously loved blue corpses and all kinds of "dismemberment". And his still life is appropriate.

Camille Pissarro, Still Life with Apples and a Jug, 1872

Claude Monet "Still life with pears and grapes", 1867.

He had still lifes, they were, but relatively few.

Auguste Renoir, Still Life with Large Flower Vase, 1866

He, in comparison with the others presented here, has quite a lot of still lifes. And what! One of his contemporaries said that he does not have sad works, and I adore him, so I shoved them here. And also because his still lifes are still little known, much less than all these bathers, etc.

And you know who? Pablo Picasso! 1919

Pablo was amazingly productive! Huge number of pictures! And among them, still lifes occupy a much smaller percentage than everything else, and even then they were mostly "Cubist". That is why he was included in the selection. To give you an idea of just how crazy (but certainly talented!) and fickle he was, take a look at the picture below. This is also him, and in the same year!

Pablo Picasso "Still life on a chest of drawers", 1919

Paul Gauguin "Ham", 1889.

Tahitian women later went, he left for Tahiti after 2 years (now I will add and go dig in the refrigerator).

Edouard Manet, Carnations and Clematis in a Crystal Vase, 1882

There are also wonderful works, such as "Roses in a glass of champagne", but Manet's still lifes in his legacy are always in the background. And in vain, right?

François Millet, 1860s.

Just a dinner for all his peasants and reapers.

Berthe Morisot "Blue Vase", 1888

Still couldn't resist!

Frederic Basil. "Still life with fish", 1866

Simple and even rude, but I think I even smell the fish! Should I go take out the trash?

Henri "Customs Officer" Rousseau, "Bouquet of Flowers", 1910

Unexpected in genre, but invariably in style. The simple-minded customs officer was always true to himself.

Everyone, thank you for your attention!

How are you?

PS. And yet Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, for he is beautiful!:

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin "Violin in a case", 1916, Odessa Museum of Art

He has quite a few still lifes. Wonderful, just wonderful! Such bright, summer ones - be sure to look on the Web, move aside the red horse and other revolutionary paraphernalia! But, since we have a post about unusual still lifes, I chose the most atypical one for this author.

Thanks again for your attention!

Let's move on to the final stage of this series of posts about the still life genre. It will be dedicated to the work of Russian artists.

Let's start with Fyodor Petrovich Tolstoy (1783-1873). Still life graphics by F.P. Tolstoy, a famous Russian sculptor, medalist, draftsman and painter, probably the most outstanding and valuable part of his creative heritage, although the artist himself said that he created these works "in his free time from serious studies."

The main property of Tolstoy's still life drawings is their illusory nature. The artist carefully copied nature. He tried, according to him own words, “with strict clarity, transfer the copied flower from life to paper as it is, with all the smallest details belonging to this flower.” To mislead the viewer, Tolstoy used such illusionistic techniques as the image of dew drops or translucent paper covering the drawing and helping to deceive the eye.

Ilya Efimofich Repin (1844-1930) also repeatedly turned to such a still life motif as flowers. These works include the painting “Autumn Bouquet” (1892, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), where the artist depicts an autumn landscape with equal attention, a young woman standing against the backdrop of golden trees, and a modest bouquet of yellow and white flowers in her hands.

I. Repin. Autumn bouquet. Portrait of Vera Repina. 1892, Tretyakov Gallery

The history of the painting “Apples and Leaves” is somewhat unusual. The still life, combining fruits and leaves, was staged for Repin's student, V.A. Serov. The teacher liked the subject composition so much that he decided to write such a still life himself. Flowers and fruits attracted many artists, who preferred these, among other things, to show the world of nature most poetically and beautifully. Even I.N. Kramskoy, who was dismissive of this genre, also paid tribute to still life, creating a spectacular painting “Bouquet of Flowers. Phloxes” (1884, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow).

Valentin Alexandrovich Serov (1865-1911) is known to most of us as an artist who paid attention in his work to landscape, portrait and historical painting. However, it should be noted that the subject in his work always played important role and often occupied the same equal position as other elements of the composition. A little higher, I already mentioned his student work "Apples on the Leaves", 1879, made under the direction of Repin. If we compare this work with a work written on the same theme by Repin, we can see that Serov's still life is more etude than the canvas of his teacher. Beginning artist used low point view, so the first and second plans are combined, and the background is reduced.

Known to everyone since childhood, the painting "Girl with Peaches" goes beyond the portrait genre and it is no coincidence that it is called "Girl with Peaches", and not "Portrait of Vera Mamontova". We can see that the features of a portrait, interior and still life are combined here. The artist pays equal attention to the image of a girl in a pink blouse and a few, but skillfully grouped objects. Pale yellow peaches, maple leaves and a shiny knife lie on a white tablecloth. Other things in the background are also lovingly drawn out: chairs, a large porcelain plate decorating the wall, a figurine of a toy soldier, a candlestick on the windowsill. Sunlight pouring from the window and falling on objects with bright highlights gives the image a poetic charm.

Mikhail Alexandrovich Vrubel (1856-1910) wrote: “And again it hits me, no, it doesn’t hit me, but I hear that intimate national note that I so want to catch on canvas and in ornament. This is the music of a whole person, not dissected by the distractions of an ordered, differentiated and pale West.”

At the Academy of Arts, Vrubel's favorite teacher was Pavel Chistyakov, who taught the young painter to "draw with form" and argued that three-dimensional forms should not be created in space with shading and contours, they should be built with lines. Thanks to him, Vrubel learned not only to show nature, but as if to have a sincere, almost loving conversation with her. In this spirit, the wonderful still life of the master “Wild Rose” (1884) was made.

Against the backdrop of exquisite drapery with floral motifs, the artist placed an elegant rounded vase painted with oriental patterns. Delicate White flower rose hips, tinted with blue-green fabric, and the leaves of the plant almost merge with the dimly shimmering black neck of the vase. This composition is full of inexpressible charm and freshness, which the viewer simply cannot help but succumb to.

During the period of illness, Vrubel began to paint more from nature, and his drawings are distinguished not only by the chased form, but also by a very special spirituality. It seems that every movement of the artist's hand betrays his suffering and passion.

Particularly noteworthy in this regard is the drawing “Still Life. Candlestick, decanter, glass”. It is a crushing triumph of fierce objectivity. Each piece of still life carries a hidden explosive power. The material from which things are made, whether it is the bronze of a candlestick, the glass of a decanter or the matte reflection of a candle, trembles perceptibly from the colossal internal stress. The pulsation is conveyed by the artist in short intersecting strokes, which makes the texture explosive and tense. Thus, objects acquire an incredible sharpness, which is true essence of things

.

G.N. Teplov and T. Ulyanov. Most often they depicted a plank wall, on which knots and veins of a tree were drawn. Various objects are hung on the walls or plugged behind nailed ribbons: scissors, combs, letters, books, music notebooks. Clocks, inkwells, bottles, candlesticks, dishes and other small things are placed on narrow shelves. It seems that such a set of items is completely random, but in fact this is far from the case. Looking at such still lifes, one can guess about the interests of artists who were engaged in playing music, reading, and who were fond of art. Masters lovingly and diligently depicted things dear to them. These paintings touch with their sincerity and immediacy of perception of nature.

Boris Mikhailovich Kustodiev (1878-1927) also devoted a lot of his work to the genre of still life. On his cheerful canvases one can see bright satin fabrics, sparkling copper samovars, the brilliance of faience and porcelain, red slices of watermelon, grape clusters, apples, mouth-watering muffins. One of his remarkable paintings is "The Merchant for Tea", 1918. It is impossible not to admire the bright splendor of the objects shown on the canvas. A sparkling samovar, bright red pulp of watermelons, glossy apples and transparent grapes, a glass vase with jam, a gilded sugar bowl and a cup standing in front of the merchant's wife - all these things bring a festive mood to the image.

In the genre of still life great attention was given to the so-called "still life-dummy". Many still lifes are “tricks”, despite the fact that they main task was the misleading of the viewer, they have undoubted artistic merit, especially noticeable in museums, where, hung on the walls, such compositions, of course, cannot deceive the public. But there are also exceptions. For example, “Still Life with Books”, made by P.G. Bogomolov, is inserted into an illusory "bookcase", and visitors do not immediately realize that this is just a picture.

Very good “Still Life with a Parrot” (1737) G.N. Teplov. With the help of clear, precise lines, turning into soft, smooth contours, light, transparent shadows, subtle color nuances, the artist shows a variety of objects hung on a plank wall. Masterfully rendered wood, bluish, pink, yellowish hues help to create an almost real feeling. fresh smell freshly cut wood.

G.N. Teplov. "Still life with a parrot", 1737, State Museum ceramics, estate Kuskovo

Russian still lifes-"tricks" of the 18th century testify to the fact that artists are still not skillfully conveying space and volumes. It is more important for them to show the texture of objects, as if transferred to the canvas from reality. Unlike Dutch still lifes, where things absorbed by the light environment are depicted in unity with it, in the paintings of Russian masters, objects painted very carefully, even petty, seem to live on their own, regardless of the surrounding space.

AT early XIX century, a great role in the further development of still life was played by the school of A.G. Venetsianov, who opposed the strict delimitation of genres and sought to teach his pupils a holistic vision of nature.

A.G. Venetsianov. Barnyard, 1821-23

The Venetian school opened a new genre for Russian art - the interior. The artists showed various rooms of the noble house: living rooms, bedrooms, studies, kitchens, classrooms, people's rooms, etc. In these works, an important place was given to the depiction of various objects, although the still life itself was of little interest to representatives of the Venetsianov circle (in any case, very few still lifes made by the famous painter's students have survived). Nevertheless, Venetsianov urged his pupils to carefully study not only the faces and figures of people, but also the things around them.

The object in Venetsianov's painting is not an accessory, it is inextricably linked with the rest of the details of the picture and is often the key to understanding the image. For example, the sickles in the painting “The Reapers” (second half of the 1820s, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg) perform a similar function. Things in Venetian art seem to be involved in the unhurried and serene life of the characters.

Although Venetsianov, in all likelihood, did not actually paint still lifes, he included this genre in his teaching system. The artist wrote: Inanimate things are not subject to those various changes that are characteristic of animate objects, they stand, hold themselves calmly, motionless before an inexperienced artist and give him time to penetrate more accurately and judiciously, to peer into the relationship of one part to another, both in lines, and in light and shadow by color itself. , which depend on the place occupied by objects”.

Of course, still life played a big role in pedagogical system Academy of Arts in the XVIII-XIX centuries (in classrooms the pupils made copies from the still lifes of the Dutch masters), but it was Venetsianov, who encouraged young artists to turn to nature, who introduced a still life into his first year of study, made up of such things as plaster figures, dishes, candlesticks, multi-colored ribbons, fruits and flowers. Venetsianov selected subjects for educational still lifes so that they were of interest to novice painters, understandable in form, beautiful in color.

In the paintings created by talented students of Venetsianov, things are conveyed truthfully and freshly. These are the still lifes of K. Zelentsov, P.E. Kornilov. In the works of the Venetians there are also works that are not essentially still lifes, but, nevertheless, the role of things in them is enormous. You can name, for example, the canvases “Study in Ostrovki” and “Reflection in the Mirror” by G.V. Magpies kept in the collection of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

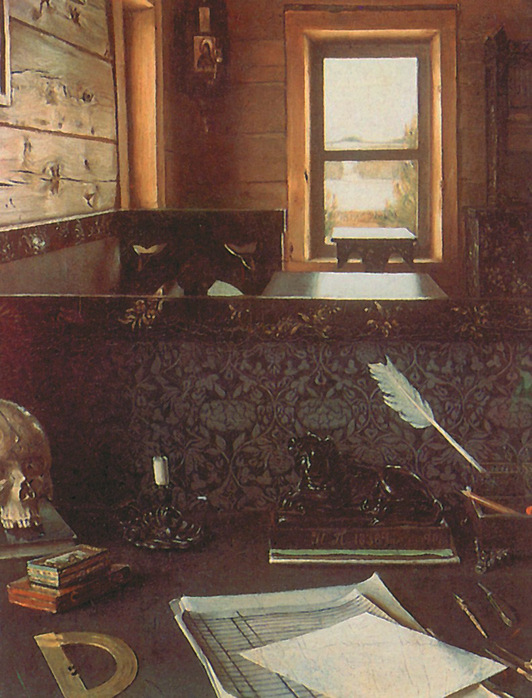

G.V. Magpie. "Office in Ostrovki". Fragment, 1844, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Still lifes in these works do not act independently, but as parts of the interior arranged in a peculiar way by the master, corresponding to the general compositional and emotional structure of the picture. The main connecting element here is light, gently passing from one object to another. Looking at the canvases, you understand how interesting the world an artist who lovingly depicted every object, every smallest little thing.

The still life presented in the “Study in Ostrovki”, although it occupies a small place in the overall composition, seems unusually significant, highlighted due to the fact that the author fenced it off from the rest of the space with a high back of the sofa, and cut it off on the left and right with a frame. It seems that Magpie was so carried away by the objects lying on the table that he almost forgot about the rest of the details of the picture. The master carefully wrote out everything: a quill pen, a pencil, a compass, a protractor, a penknife, an abacus, sheets of paper, a candle in a candlestick. The point of view from above allows you to see all things, none of them obscures the other. Attributes such as a skull, a clock, as well as symbols of “earthly vanity” (a figurine, papers, abacus) allow some researchers to classify the still life as a vanitas, although this coincidence is purely coincidental, most likely, the serf artist used what was on the table his master.

The famous master of subject compositions of the first half of XIX century was the artist I.F. Khrutsky, who painted many beautiful paintings in the spirit of the Dutch still life XVII century. Among his best works are “Flowers and Fruits” (1836, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), “Portrait of a Wife with Flowers and Fruits” (1838, Art Museum of Belarus, Minsk), “Still Life” (1839, Museum of the Academy of Arts, St. Petersburg).

In the first half of the 19th century in Russia, the “botanical still life”, which came to us from Western Europe. In France, at that time, works of botanists with beautiful illustrations were published. Greater fame in many European countries received by the artist P.Zh. Redoubt, who was considered "the most celebrated flower painter of his time." "Botanical drawing" was a significant phenomenon not only for science, but also for art and culture. Such drawings were presented as a gift, decorated albums, which thus put them on a par with other works of painting and graphics.

In the second half of the 19th century, P.A. Fedotov. Although he did not actually paint still lifes, the world of things he created delights with its beauty and truthfulness.

Objects in Fedotov's works are inseparable from people's lives, they are directly involved in the dramatic events depicted by the artist.

Looking at the painting “The Fresh Cavalier” (“Morning after the Feast”, 1846), one is amazed at the abundance of objects carefully painted by the master. A real still life, surprising with its laconicism, is presented in the famous painting by Fedotov “Courtship of a Major” (1848). The glass is palpably real: wine glasses on high legs, a bottle, a decanter. The thinnest and transparent, it seems to emit a gentle crystal ringing.

Fedotov P.A. Major's marriage. 1848-1849. GTG

Fedotov does not separate objects from the interior, so things are shown not only reliably, but also picturesquely subtly. Every most ordinary or not very attractive object that takes its place in the common space seems amazing and beautiful.

Although Fedotov did not paint still lifes, he showed an undoubted interest in this genre. Intuition prompted him how to arrange this or that object, from what point of view to present it, what things would look next not only logically justified, but also expressively.

The world of things, which helps to show a person's life in all its manifestations, endows Fedotov's works with a special musicality. Such are the paintings “Anchor, more anchor” (1851-1852), “The Widow” (1852) and many others.

In the second half of the 19th century, the still life genre practically ceased to interest artists, although many genre painters willingly included still life elements in their compositions. Things in the paintings of V.G. Perov (“Tea drinking in Mytishchi”, 1862, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), L.I. Solomatkin (“Slavilshchiki-gorodovye”, 1846, State historical Museum, Moscow).

![]()

Still lifes are presented in genre scenes by A.L. Yushanova (“Seeing off the chief”, 1864), M.K. Klodt (“The Sick Musician”, 1855), V.I. Jacobi (“Pedlar”, 1858), A.I. Korzukhin (“Before confession”, 1877; “In the monastery hotel”, 1882), K.E. Makovsky (“Alekseich”, 1882). All these canvases are now kept in the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery.

K.E. Makovsky. “Alekseich”, 1882, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

In the 1870s-1880s, everyday life remained the leading genre in Russian painting, although landscape and portrait also occupied an important place. a huge role for further development Russian art was played by the Wanderers, who sought to show the truth of life in their works. Artists began to give great importance working from nature and therefore increasingly turned to landscape and still life, although many of them considered the latter a waste of time, a senseless passion for form, devoid of internal content. So, I.N. Kramskoy mentioned the famous French painter, who did not neglect still lifes, in a letter to V.M. Vasnetsov: “A talented person will not waste time on the image, for example, basins, fish, etc. It’s good to do this for people who already have everything, but we have a lot of work to do.”

Nevertheless, many Russian artists who did not paint still lifes admired them, looking at the canvases of Western masters. For example, V.D. Polenov, who was in France, wrote to I.N. Kramskoy: “Look how things are going here, like clockwork, everyone works in his own way, in a variety of directions, what anyone likes, and all this is appreciated and paid. With us, what matters most is what is done, but here it is how it is done. For example, for a copper basin with two fish they pay twenty thousand francs, and in addition they consider this copper craftsman the first painter, and, perhaps, not without reason.

Visited in 1883 at an exhibition in Paris V.I. Surikov admired landscapes, still lifes and paintings depicting flowers. He wrote: “Gibert's fish are good. Fish slime is conveyed masterfully, colorfully, kneaded tone on tone.” There is in his letter to P.M. Tretyakov and such words: “And Gilbert's fish are a miracle. Well, you can completely take it in your hands, it’s written to deceit. ”

Both Polenov and Surikov could become excellent masters of still life, as evidenced by the masterfully painted objects in their compositions (“Sick” by Polenova, “Menshikov in Berezov” by Surikov).

V.D. Polenov. “Sick”, 1886, Tretyakov Gallery

Most of the still lifes created by famous Russian artists in the 1870s and 1880s are works of a sketch nature, showing the authors' desire to convey the features of things. Some of these works depict unusual, rare objects (for example, a study with a still life for I.E. Repin's painting "Cossacks write a letter to the Turkish Sultan", 1891). Self value such works did not exist.

Still lifes by A.D. Litovchenko, made as preparatory sketches for the large canvas “Ivan the Terrible Shows His Treasures to Ambassador Horsey” (1875, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg). The artist showed luxurious brocade fabrics, weapons inlaid precious stones, gold and silver items stored in the royal treasuries.

More rare at that time were etude still lifes, representing ordinary household items. Such works were created with the aim of studying the structure of things, and were also the result of an exercise in painting technique.

Still life played an important role not only in genre painting, but also in portraiture. For example, in the picture I.N. Kramskoy “Nekrasov in the period of the Last Songs” (1877-1878, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), objects serve as accessories. S.N. Goldstein, who studied Kramskoy’s work, writes: “In search of the overall composition of the work, he strives to ensure that the interior he recreates, despite his own everyday character, primarily contributes to the awareness of the spiritual image of the poet, the unfading significance of his poetry. And indeed, the individual accessories of this interior - the volumes of Sovremennik, randomly stacked on a table by the patient's bedside, a sheet of paper and a pencil in his weakened hands, a bust of Belinsky, a portrait of Dobrolyubov hanging on the wall - acquired in this work a meaning by no means external signs situations, but relics closely related to the image of a person.

Among the few still lifes of the Wanderers, the main place is occupied by “bouquets”. An interesting “Bouquet” by V.D. Polenov (1880, Abramtsevo Estate Museum), in the manner of execution a bit reminiscent of the still lifes of I.E. Repin. Unpretentious in its motive (small wild flowers in a simple glass vase), he nevertheless delights with his free painting. In the second half of the 1880s, similar bouquets appeared in the paintings of I.I. Levitan.

In a different way, I.N. demonstrates the flowers to the viewer. Kramskoy. Many researchers believe that two paintings are “Bouquet of Flowers. Phloxes” (1884, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) and “Roses” (1884, collection of R.K. Viktorova, Moscow) were created by the master while working on the canvas “Inconsolable Sorrow”.

Kramskoy demonstrated two “bouquets” at the XII Traveling Exhibition. Spectacular, bright compositions depicting garden flowers on a dark background found buyers even before the opening of the exhibition. The owners of these works were Baron G.O. Gunzburg and the Empress.

At the IX Traveling Exhibition of 1881-1882, the attention of the public was attracted by the painting by K.E. Makovsky, named in the catalog "Nature morte" (now it is in the Tretyakov Gallery under the name "In the artist's studio"). The large canvas depicts a huge dog lying on a carpet and a child reaching out from an armchair to fruit on the table. But these figures are just the details that the author needs in order to revive the still life - a lot of luxurious things in the artist's studio. Written in the traditions of Flemish art, Makovsky's painting still touches the viewer's soul. The artist, carried away by the transfer of the beauty of expensive things, failed to show their individuality and created a work, the main objective which is a demonstration of wealth and luxury.

All the objects in the picture seem to be collected in order to amaze the viewer with their splendor. On the table is a traditional still life set of fruits - large apples, pears and grapes on a large beautiful dish. There is also a large silver mug, decorated with ornaments. Nearby stands a white-and-blue faience vessel, next to which is a richly decorated ancient weapon. The fact that this is an artist's workshop is reminiscent of brushes placed in a wide jug on the floor. The gilded armchair has a sword in a luxurious scabbard. The floor is covered with a carpet with a bright ornament. Expensive fabrics also serve as decoration - brocade trimmed with thick fur, and velvet from which the curtain is sewn. The color of the canvas is sustained in saturated shades with a predominance of scarlet, blue, golden.

From all of the above, it is clear that in the second half of the 19th century, still life did not play a significant role in Russian painting. It was distributed only as a study for a painting or an educational study. Many artists who painted still lifes within academic program, in independent work, they did not return to this genre anymore. Still lifes were painted mainly by non-professionals who created watercolors with flowers, berries, fruits, mushrooms. Major masters did not consider the still life worthy of attention and used objects only to convincingly show the setting and decorate the image.

The first beginnings of a new still life can be found in the paintings of artists who worked at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries: I.I. Levitan, I.E. Grabar, V.E. Borisov-Musatov, M.F. Larionova, K.A. Korovin. It was at that time that the still life appeared in Russian art as an independent genre.

But it was a very peculiar still life, understood by artists who worked in an impressionistic manner, not as an ordinary closed subject composition. The masters depicted the details of a still life in a landscape or interior, and it was not so much the life of things that was important to them, but the space itself, a haze of light that dissolves the outlines of objects. Of great interest are also graphic still lifes by M.A. Vrubel, distinguished by their unique originality.

At the beginning of the 20th century, such artists as A.Ya. Golovin, S.Yu. Sudeikin, A.F. Gaush, B.I. Anisfeld, I.S. Schoolboy. A new word in this genre was also said by N.N. Sapunov, who created whole line panel paintings with bouquets of flowers.

In the 1900s, many artists of various directions turned to still life. Among them were the so-called. Moscow sezannists, symbolists (P.V. Kuznetsov, K.S. Petrov-Vodkin), etc. important place subject compositions occupied in the work of such famous masters as M.F. Larionov, N.S. Goncharova, A.V. Lentulov, R.R. Falk, P.P. Konchalovsky, A.V. Shevchenko, D.P. Shterenberg, who made the still life full-fledged among other genres in Russian painting of the 20th century.

One listing of Russian artists who used elements of still life in their work would take up a lot of space. Therefore, we restrict ourselves to the material presented here. Those interested can learn more about the links provided in the first part of this series of posts about the genre of still life.

Previous posts: Part 1 -

Part 2 -

Part 3 -

Part 4 -

Part 5 -

About some iconic artists who created still life paintings.

Introduction

The term "still life" is used to define paintings depicting inanimate objects (from the Latin "dead nature"). Moreover, objects can be natural origin(fruits, flowers, dead animals and insects, skulls, etc.), and man-made (various utensils, watches, books and scrolls of paper, Jewelry and so on). Often, a still life includes some hidden subtext, conveyed through a symbolic image. Works of an allegorical nature belong to the subgenre "vanitas".

Still life as a genre was most developed in Holland in the 17th century as a way to protest against the established church and the imposition of religious art. AT further history paintings by the Dutch of that time (Utrech, Leiden, Delft and others) a huge impact on the development of art: composition, perspective, the use of symbolism as an element of narration. Despite its importance and interest from the public, according to the academies of arts, still life occupied the last place in the general hierarchy of genres.

Rachel Ruysch

Ruysch is one of the most famous Dutch realists and still life painters. The compositions of this artist contain a lot of symbolism, various moral and religious messages. Her signature style is a combination of a dark background, meticulous attention to detail, delicate coloring and the image of additional elements that add interest (insects, birds, reptiles, crystal vases).

Harmen van Stenwijk

The work of this Dutch realist perfectly demonstrates still lifes in the vanitas style, illustrating the hustle and bustle of earthly life. One of the most famous paintings is "Allegory of the Vanity of Human Life", which shows a human skull in the rays sunlight. Various items the compositions refer to the ideas of the inevitability of physical death. The detail and level of realism in Stenwijk's paintings is achieved through the use of fine brushes and paint application techniques.

Paul Cezanne

Known for his landscapes, portraits and genre works, Cezanne also contributed to the development of the still life. After the interest in Impressionism faded, the artist began to explore fruits and natural objects, experiment with three-dimensional figures. These studies helped create perspective and dimension in still life paintings, not only through classical techniques, but also through the masterful use of color. All the directions considered by Cezanne were further studied by Georges Braque and Picasso in the development of analytical cubism. In pursuit of the goal of creating something "permanent", the artist preferred to paint the same objects, and the incredibly long process of creating a still life led to the fact that fruits and vegetables began to rot and decompose long before the painting was completed.

Khem

A student of David Bailly, the Dutch realist Hem is known for his magnificent still lifes with a large number of details, loaded with compositions, an abundance of insects and other decorative and symbolic elements. Often the artist used religious motifs in his works, like Jan Brueghel and Federico Borromeo.

Jean Baptiste Chardin

The carpenter's son Jean Chardin acquired his industriousness and craving for order precisely thanks to his father. The master's paintings are often calm and sober, because he strove for harmony of tone, color and form, largely achieved through work with lighting and contrasts. The desire for purity and order is also expressed in the absence of allegories in the compositions.

Frans Snyders

The author of baroque still lifes and animal scenes was an incredibly prolific master, and his ability to depict the texture of leather, fur, glass, metal and other materials was unsurpassed. Snyders was also a prominent animal painter, often depicting dead animals in his still lifes. Later, he becomes the official painter of the Archduke Albert of Austria, which resulted in the creation of another more masterpieces.

Francisco de Zurbaran

Zurbaran - famous author paintings on a religious theme - is one of the greatest creators of still lifes. Painted in the strict Spanish tradition, his work has a timeless quality and impeccable simplicity. As a rule, they represent a small number of objects against a darkened background.

Conor Walton

From contemporary authors Noteworthy is Conor Walton. The contribution of the Irish artist to the development of still life can be clearly seen in the works "Hidden: Oranges and Lemons" (2008), "Still Life with Large Orchids" (2004). The craftsman's work is precise and executed with exceptional use of light to help convey the textures of various surfaces.

The best still lifes

updated: June 4, 2017 by: Gleb Oratory as a prototype of journalism

Oratory as a prototype of journalism Quotes about Napoleon - dslinkov — LiveJournal

Quotes about Napoleon - dslinkov — LiveJournal Me vengeance The man on the bulldozer destroyed the city

Me vengeance The man on the bulldozer destroyed the city